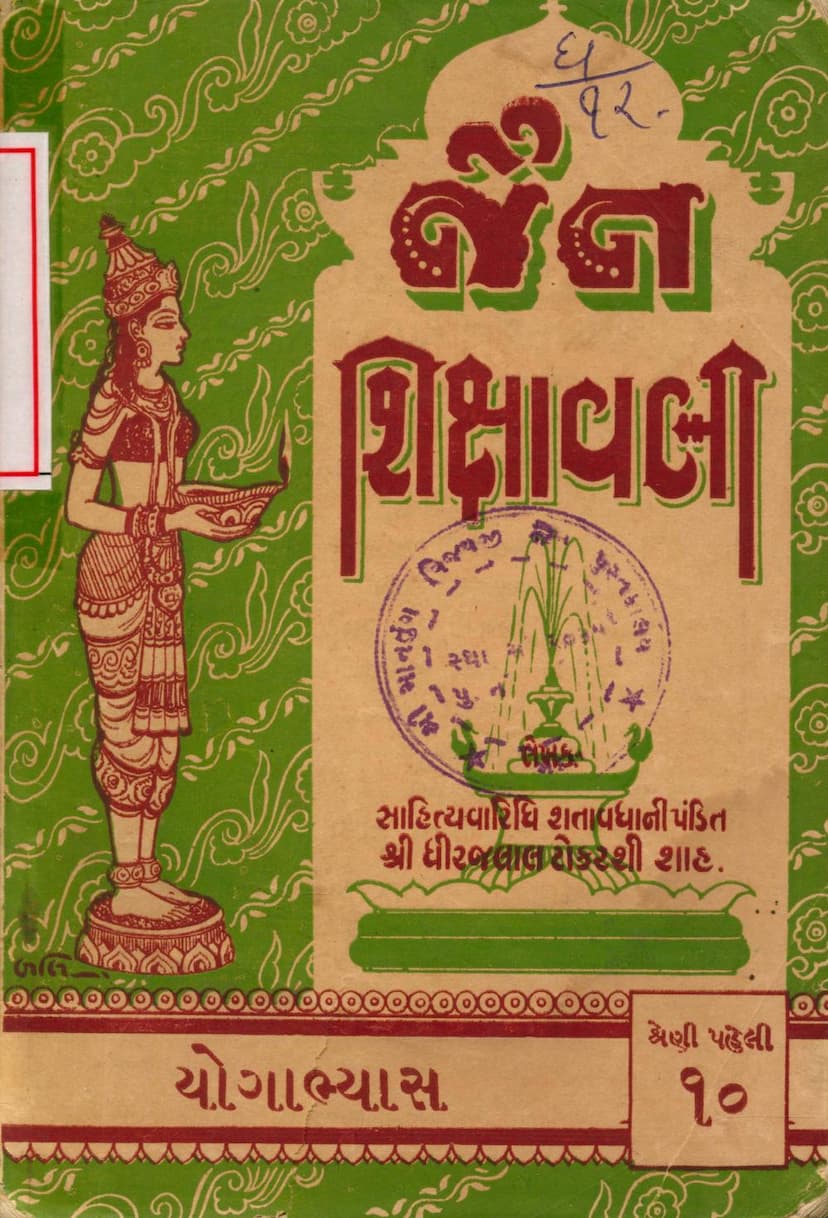

Jain Shikshavali Yogabhyas

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jain Shikshavali Yogabhyas" by Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Jain Shikshavali Yogabhyas (Jain Education Series: Yoga Practice) Author: Pt. Shrimad Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah (Sahityavaridhi Shatavadhani) Publisher: Jain Sahitya Prakashan Mandir, Mumbai

This book is the tenth in the "Jain Shikshavali" series, which aims to present Jain philosophy and conduct in a simple and accessible style. This specific volume focuses on the practice of Yoga within the Jain tradition.

Core Message:

The central theme of the book is to establish that Yoga is an integral and essential component of Jainism, not merely an external practice for ascetics or renunciates. It emphasizes that Yoga is a path to liberation (Moksha) and the refinement of one's life.

Key Points and Concepts Discussed:

-

The Glory of Yoga (Yogana Mahima):

- Jainism is described as both Ahimsa (non-violence) and Yoga-centric, though the latter aspect is often overlooked.

- Many misconceptions exist that Yoga is only for hermits or ascetics, but the text clarifies that true sainthood (Sadhu) is defined by the practice of Yoga for liberation.

- Ancient Jain acharyas like Bhadrabahuswami, Jinvallabhagani Kshamasramana, and Mantungsuri have lauded the Tirthankaras (Jain spiritual leaders) as great Yogis, emphasizing Yoga's importance in Jain life.

- Yoga is praised as a supreme wish-fulfilling tree, an excellent wish-fulfilling gem, the foremost among all dharmas (duties/virtues), and the gateway to liberation.

- Yoga is stated to destroy the seed of rebirth, be the great remedy for aging, the cure for suffering, and the means to overcome death, leading to immortality.

- Yoga cultivates qualities like contentment (dhruti), forgiveness (kshama), good conduct (sadachar), increasing spiritual inclination (yogavruddhi), auspicious beginnings (shubhoday), respectability (aadriyeta), dignity (gurutva), and supreme peace and happiness (shamsaukhya).

- It removes stubbornness and prejudice, promotes tolerance for dualities (pleasure and pain), stabilizes the mind, fosters faith, cultivates friendship, makes one dear to others, and bestows insightful intellect.

-

Instructions Regarding Yoga Practice (Yogana Abhyas Ange Ketlik Suchanao):

- The text acknowledges that the desire to practice Yoga often arises but is not acted upon due to an inability to change daily routines.

- It counters the idea that Yoga is too difficult, citing the principle that "with practice, everything can be achieved."

- The book emphasizes that consistent practice can stabilize an unstable mind, control the vital breath (prana), lead to supreme bliss, and ultimately result in self-realization.

-

Qualities Required for a Yoga Practitioner (Yogabhyas Karanarma Hova Joita Guna):

- Six essential qualities are highlighted: enthusiasm (utsaha), courage (sahas), patience (dhairya), knowledge of reality (tattva-jnana), firm resolve (nishchaya), and renunciation of worldly company (janasangaparityaga).

- These qualities are elaborated: enthusiasm drives action, courage helps overcome obstacles, patience navigates difficulties, philosophical knowledge provides a stable support, firm resolve ensures completion of tasks, and avoiding worldly company prevents mental distractions.

- Furthermore, for those seeking self-discovery through Yoga, the text strongly advises abandoning excessive ornamentation, association with the opposite sex, and indulging in rich, flavorful foods, comparing these to poison. This is a crucial point, as the author notes the lack of adherence to these principles in some modern Yoga ashrams.

-

The Necessity of a Guru (Guru-ni Avashyakta):

- The paramount importance of a qualified Guru for Yoga practice is stressed. The saying "Without a Guru, there is no knowledge" is cited.

- While finding a suitable Guru may be challenging, genuine seekers will find one, as stated in the proverb "Where there is a seeker, there is a Guru." (The book refers to another publication in the series, "Sadguru Seva," for a deeper discussion on Gurus).

-

Definition of Yoga (Yogani Vyakhyan):

- Drawing from Yogavishika by Shri Haribhadrasuri, Yoga is defined generally as any spiritual practice leading to liberation (Moksha). More specifically, it refers to practices related to posture, recitation, contemplation, and concentration.

- Haribhadrasuri elaborates on five types of Yoga:

- Sthanadigat (Postural/Locational): Refers to practices related to postures (like Kayotsarga).

- Varnagat (Recitational/Verbal): Refers to the contemplation of scriptures or words of the Vitaragas (Jinas).

- Arthagat (Meaning-oriented): Refers to the contemplation of the subject matter of scriptures.

- Alambanagat (Object-oriented): Refers to taking support from Jin-images or scriptures.

- Alambanrahit (Objectless): Refers to the state of oneness with the attributes of the soul (like omniscience) without any external support, leading to a state of absorption.

- Shrimad Yashovijayji supports this, defining Yoga as any practice that unites the soul with liberation, specifically mentioning practices related to posture, reciting scriptures, contemplation, and single-pointed concentration. The essence is the joyful adherence to Knowledge, Vision, and Conduct.

- Acharya Hemachandra defines Yoga as the cause of Moksha, which is the primary of the four aims of life (Dharma, Artha, Kama, Moksha), and this cause is the "three jewels" of Right Faith, Right Knowledge, and Right Conduct.

- The general Jain definition of Yoga encompasses all actions and practices that lead to Moksha, with a specific emphasis on steady contemplation and meditation on the teachings of the Vitaragas, often through postures like Kayotsarga or by focusing on their images.

-

Purpose of Meditation Siddhi (Dhyana Siddhi-nu Prayojan):

- Achieving a state free from karmas is essential for Moksha, and this state is unattainable without meditation.

- The text clarifies that Tapa (asceticism) in Jainism is broadly defined and includes meditation. Tapa is divided into external (Bahya) and internal (Abhyantar). Meditation is one of the six types of internal Tapa.

- Meditation is considered the highest form of internal Tapa, capable of quickly burning karmas like a blazing fire and revealing the soul's pure nature. The liberation of all past, present, and future souls is attributed to meditation.

- Other external Tapa practices like fasting, reduced intake, renunciation of specific foods, etc., are considered supportive of meditation.

-

Definition and Types of Meditation (Dhyani-ni Vyakhyan ane Tena Prakaro):

- Meditation is defined as concentrating the mind on a subject of contemplation and restraining the activities of mind, speech, and body.

- Two main categories of meditation exist:

- Ashubha (Inauspicious):

- Arta Dhyana (Lamenting Meditation): Focused on suffering, pain, loss of beloved things, or intense desires. It has four types: lamenting over undesired contact, loss of desired objects, painful experiences, and intense craving for enjoyments.

- Raudra Dhyana (Fierce Meditation): Characterized by violence, anger, hatred, and deception. It has four types: meditation related to violence, falsehood, theft, and protection of possessions. Both Arta and Raudra Dhyana lead to the binding of inauspicious karmas and are to be abandoned.

- Shubha (Auspicious):

- Dharma Dhyana (Virtuous Meditation): Contemplation of virtuous principles, the consequences of actions, and the nature of reality. It has four types: contemplation of divine commands, the futility of worldly pleasures, the results of karma, and the nature of matter and space.

- Shukla Dhyana (Pure Meditation): The highest form of meditation, leading to liberation. It also has four types:

- Pruthaktva-vitarka-savichara: Differentiating and analyzing the object of meditation (e.g., understanding production, decay, permanence, form, formlessness).

- Ekatva-vitarka-nirvichara: Unified contemplation on a single aspect of an object or entity. This stage calms the mind completely.

- Sukshma-kriya-pratipaati: Achieved by the soul liberated from gross activities, focusing on subtle vital functions.

- Samoocchinnakriya-anivarti: The state where even subtle vital functions cease, and the soul becomes completely free and motionless, leading to omniscience and eternal bliss. The last two are objectless.

- Ashubha (Inauspicious):

-

Yama-Niyama:

- The text compares the Jain approach to the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Yajnavalkya Smriti, which list Yama and Niyama as preliminary stages.

- While these are not explicitly enumerated as separate "Yama" and "Niyama" in the same way, Jainism integrates their essence within its framework of Charitra (conduct).

- Jain acharyas classify the causes of karmic influx (asrava) into five main categories: Avrata (lack of vows), Kashaya (passions), Indriya (senses), Yoga (activity of mind, speech, body), and 25 specific actions.

- The five Yamas described by Patanjali (non-violence, truth, non-stealing, celibacy, non-possession) are seen as corresponding to the renunciation of these asrava gateways.

- The Yamas and Niyamas found in other traditions (like purity, contentment, penance, study, devotion to God) are largely incorporated into the Jain concept of Yati-dharma (conduct of ascetics) and general ethical principles.

- Shaucha (purity) is emphasized through mind control, regulated speech, and bodily discipline (guptis).

- Santosh (contentment) is achieved by conquering the four passions (Kashayas), especially greed.

- Tapa (asceticism) is considered the lifeblood of Jainism.

- Swadhyaya (study) and Ishwarpranidhan (devotion to the supreme soul/Tirthankaras) are also highly valued.

-

Place and Environment for Yoga Practice (Yogabhyas Mate Desh ane Sthan):

- While yogic texts describe specific ideal locations (clean, quiet, free from disturbances), Jain tradition emphasizes adaptability.

- Jain ascetics generally move from place to place, especially during the monsoon months when life is abundant. They choose secluded places for contemplation like deserted rooms, rest houses, cremation grounds, forests, or caves.

- Crucially, Jain practice involves enduring hardships (parishahas) like cold, heat, hunger, thirst, etc., without attachment or aversion. This fosters detachment from the body.

- The text notes that even places with non-religious rulers or hostile populations are not avoided, and such challenges can be overcome by spiritual strength.

- The ideal environment is one free from excessive noise and sharp, thorny vegetation.

-

Mastery of Postures (Asana Siddhi):

- In Jainism, Kayotsarga (standing in a posture of abandoning the body, often with arms hanging loose) is a primary posture for meditation. It can also be performed sitting or lying down.

- Detailed instructions for performing Kayotsarga are provided, emphasizing a specific leg stance, proper posture, and holding of monastic implements (muhapti, rajoharan).

- The text lists 19 common faults to avoid during posture practice, such as improper leg positions, swaying, leaning, and distracting eye movements.

- The benefits of mastering postures are stated as overcoming disturbances from heat, cold, hunger, thirst, and other dualities, leading to mental stability and the ability to meditate effectively.

-

Pranayama (Breath Control):

- Unlike many other yoga traditions, Jain texts generally do not emphasize forceful Pranayama.

- The rationale is that forceful breath control can disturb the mind rather than calm it, leading to mental distress and hindering liberation.

- The text quotes Hemachandracharya and Shubhandracharya who state that the mind does not find peace through forced Pranayama and that it can even be an obstacle to liberation, especially for those already detached and calm.

- However, it acknowledges the concept of "Bhava Pranayama" (meditative breath control) where exhalation is associated with renouncing external attachments, inhalation with internal focus, and retention with stability.

-

Pratyahara (Sense Withdrawal):

- The withdrawal of the senses from their objects is recognized as essential.

- Hemachandracharya states that after withdrawing the mind and senses from worldly objects, the mind should be made steady for Dharma Dhyana.

- Shubhandracharya defines Pratyahara as the ability of a calm-minded sage to withdraw their senses and mind from their objects and direct them at will to a desired focus. This leads to a stable mind, like a tortoise withdrawing its limbs, facilitating meditation.

-

Dharana (Concentration):

- Dharana is considered useful for achieving meditation. It involves firmly holding the mind on a chosen object (conscious or unconscious, scripture, meaning, substance, or its modifications).

- The text mentions the Jain practice of fixing the gaze on the tip of the nose or other specific points (navel, heart, forehead) as a form of Dharana.

- Lord Mahavir's practice of gazing intently at a clod of earth for an entire night is cited as an example.

-

Adhyatma and Bhavana (Self-Reflection and Contemplation):

- Jain sages frequently use the terms Adhyatma (self-reflection) and Bhavana (contemplation) instead of the more technical yogic terms. These practices are seen as simplifying the path to meditation.

- Adhyatma is defined as engaging in the right path with vigilance.

- Bhavana refers to specific contemplations that purify the mind.

- Twelve types of Bhavana are elaborated: Impermanence, Homelessness (lack of refuge), Cycle of Birth and Death, Oneness, Otherness, Impurity, Influx of Karma, Cessation of Karma, Shedding of Karma, True Dharma, Nature of the Universe, and Rarity of Enlightenment. These Bhavanas are said to encompass the essence of virtuous contemplation.

- The text also mentions the four Brahmaviharas (states of sublime living): Maitri (friendliness), Pramoda (joy in virtue), Karunya (compassion), and Madhyastha (equanimity). These are considered vital for achieving Samata (equanimity) and are highly praised.

-

Meditation Siddhi and Samadhi (Meditation Achievement and Absorption):

- Jain sages recognize three states of the mind: wandering, sustained thought, and focused concentration. The third is meditation.

- Meditation is considered achieved when the mind remains concentrated on a single subject for a brief period (one Antarmuhurta - roughly 48 minutes).

- This applies to those bound by karma. For omniscient beings, meditation is their very nature.

- The text notes that only those with excellent physical constitution can achieve profound meditation, while others can achieve mental peace and tranquility. Meditation's fruit is equanimity, leading to Samadhi.

-

Types of Yoga (Yogana Prakare):

- The text compares Jain Yoga to the Vedic Yoga paths of Bhakti Yoga (devotion), Jnana Yoga (knowledge), and Karma Yoga (action).

- In Jainism, Samyakdarshan (Right Faith) corresponds to Bhakti Yoga.

- Samyagnana (Right Knowledge) corresponds to Jnana Yoga.

- Samyakcharitra (Right Conduct) corresponds to Karma Yoga.

- Furthermore, the five types of Yoga identified by Haribhadrasuri (Sthana, Varna, Artha, Alambana, Alambanrahit) are further categorized based on intention, activity, stability, and accomplishment, leading to various classifications of Jain Yoga.

-

Conclusion (Upasanhar):

- The book concludes by reiterating the Jain tradition's deep appreciation for Yoga and its well-defined methods for its practice.

- It encourages readers to study relevant texts like Yoga Dristi Samucchaya, Yoga Vishika, Yoga Shastra, Jnanaarnava, etc., and to seek guidance from experienced practitioners.

- The text highlights that Jain Yoga practice is characterized as simple, active, and capable of quickly bringing peace and stability to the mind, thus holding a special place in the broader tradition of Indian Yoga.

In essence, "Jain Shikshavali Yogabhyas" presents a unique perspective on Yoga rooted in Jain philosophy, emphasizing its spiritual efficacy for liberation and personal refinement, integrated seamlessly with the core principles of Jain conduct and asceticism.