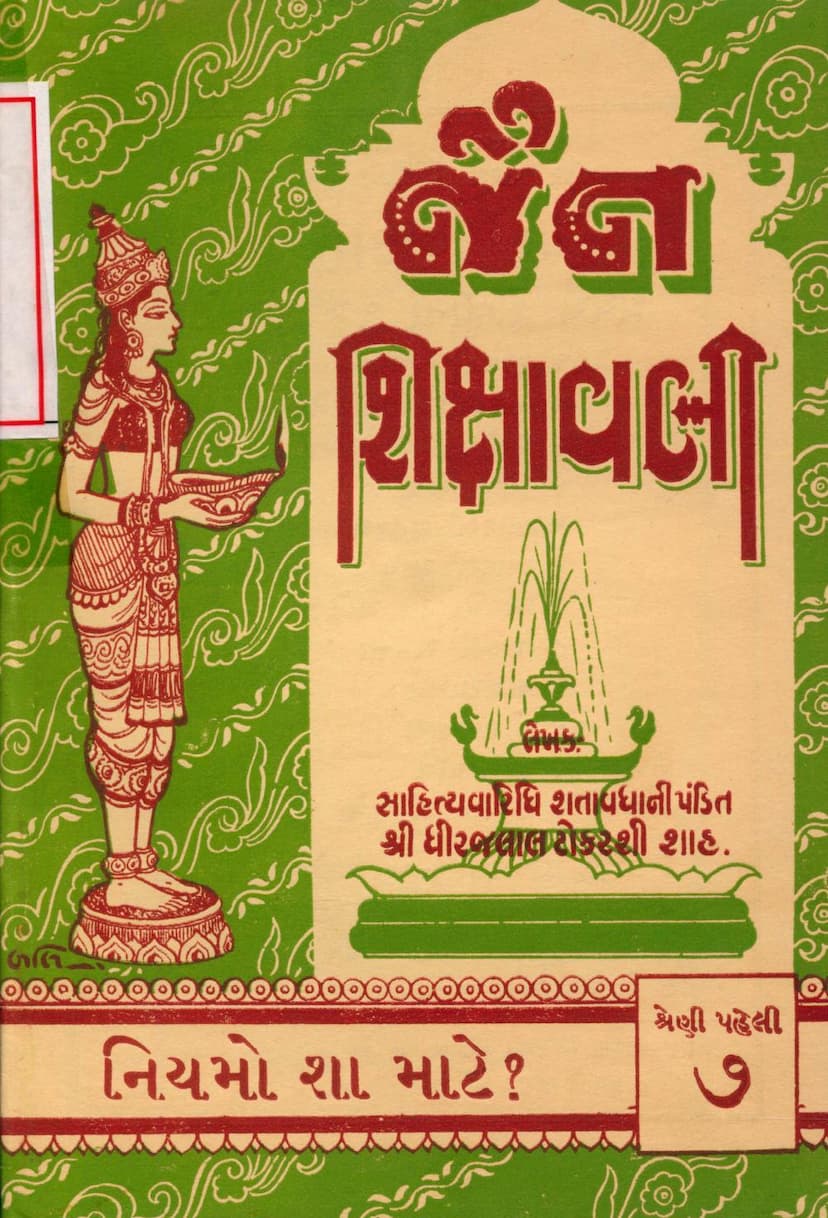

Jain Shikshavali Niyamo Sha Mate

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This document is the seventh booklet in the first series of the "Jain Shikshavali" (Jain Teachings) series, titled "Niyamo Sha Mate?" (Why Rules/Vows?). Authored by Pandit Shri Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah, it was published by Jain Sahitya Prakashan Mandir.

The book advocates for the importance and necessity of adhering to rules and vows in Jainism. It argues that these regulations are not mere restrictions but are essential tools for spiritual progress and liberation.

Here's a breakdown of the key themes and arguments presented in the text:

-

Rules as the Divine Gateway to Siddhi (Liberation): The book begins by stating that according to Jain philosophy, without "charitra" (conduct/virtue), liberation is impossible. Charitra is achieved through "sanyam" (restraint/discipline), and sanyam is cultivated through vows and rules. Therefore, rules are presented as the divine gateway to the abode of liberation.

-

The Beauty and Importance of Conduct (Charitra): The text emphasizes that knowledge alone is insufficient for liberation. It cites scriptures that highlight the plight of knowledgeable individuals who, lacking proper conduct, are still trapped in the cycle of rebirth. Analogies are used to illustrate this point, such as a donkey carrying sandalwood but not benefiting from its fragrance, or a blind person unable to appreciate thousands of lamps.

-

The Significance of Sanyam (Self-Discipline): The author stresses that an unrestrained person cannot protect themselves in this world or the next, even with wealth. Greed and attachment blind individuals to the right path. The examples of worldly attachments are contrasted with the path of sanyam, urging readers to remain vigilant and strive for self-control.

-

Debunking the Notion of "No Rules": The booklet addresses the misconception that binding oneself with strict rules makes life dull or unenjoyable. It argues that these rules are not true bonds but are the "experienced means" to break free from the bondage of senses and karma. Just as bitter medicine is necessary to cure fever, strict rules, though difficult, are beneficial. The analogy of not allowing oneself to be overly free, like a horse without reins, is used to explain the need for self-imposed discipline.

-

The Power of Practice (Abhyas): The text emphasizes that even difficult practices can be mastered through practice. It encourages individuals to start with small rules and gradually build their capacity for sanyam. The accumulation of small amounts of money to become a millionaire or the growth of a small stream into a large river are used as examples of how small, consistent efforts lead to significant results.

-

The Benefit of Small Rules: The book includes illustrative stories, such as the tale of a potter's kiln, to demonstrate how even seemingly insignificant rules can lead to unexpected benefits. It highlights the importance of consistency and the potential for growth.

-

The Virtue of Understanding Rules (and Even Without It): The story of Vankachool is used to illustrate that even rules taken without complete understanding can be beneficial if adhered to faithfully. This story shows how Vankachool's adherence to seemingly simple rules saved him from severe consequences.

-

The Imperative of Following Vows: The author strongly advocates for the strict observance of all vows taken, regardless of their size. It emphasizes that fulfilling vows builds mental fortitude, develops the quality of renunciation, strengthens conduct, and leads to inner peace. The importance of unwavering commitment, even in the face of adversity, is highlighted through the story of Sudarshan Sheth, who remained steadfast in his vows despite severe trials.

-

Rules as "Pratyakhyan" (Renunciation): The book explains that the concept of "niyam" (rule/vow) is closely aligned with "pratyakhyan" (renunciation) in Jain scriptures. It defines pratyakhyan as a statement or commitment that is unfavorable to sin, self-indulgence, and lack of restraint, and favorable to righteous conduct, self-discipline, and restraint.

-

Types of Pratyakhyan: The text elaborates on the different categories and types of pratyakhyan, including:

- Mulgun Pratyakhyan (Core Vows): Pertaining to the five great vows (mahavratas) for monks and the five lesser vows (anuvratas) for laypeople.

- Uttargun Pratyakhyan (Secondary Vows): Pertaining to additional vows and observances.

- Various classifications of pratyakhyan based on their scope, duration, and the intentions behind them.

-

The Importance of Sixfold Purity: The book concludes by outlining six types of purity required for effective pratyakhyan: Spashana (correct time), Palana (adherence to purpose), Shobhana (sharing with guests), Tirana (extending the duration), Keertana (remembering with enthusiasm), and Aradhana (with the sole aim of karmic redemption).

In essence, "Niyamo Sha Mate?" strongly asserts that rules and vows are not burdens but are fundamental pillars of the Jain path to spiritual purification and ultimate liberation. They are presented as practical guidelines for living a life of discipline, virtue, and ultimately, self-realization.