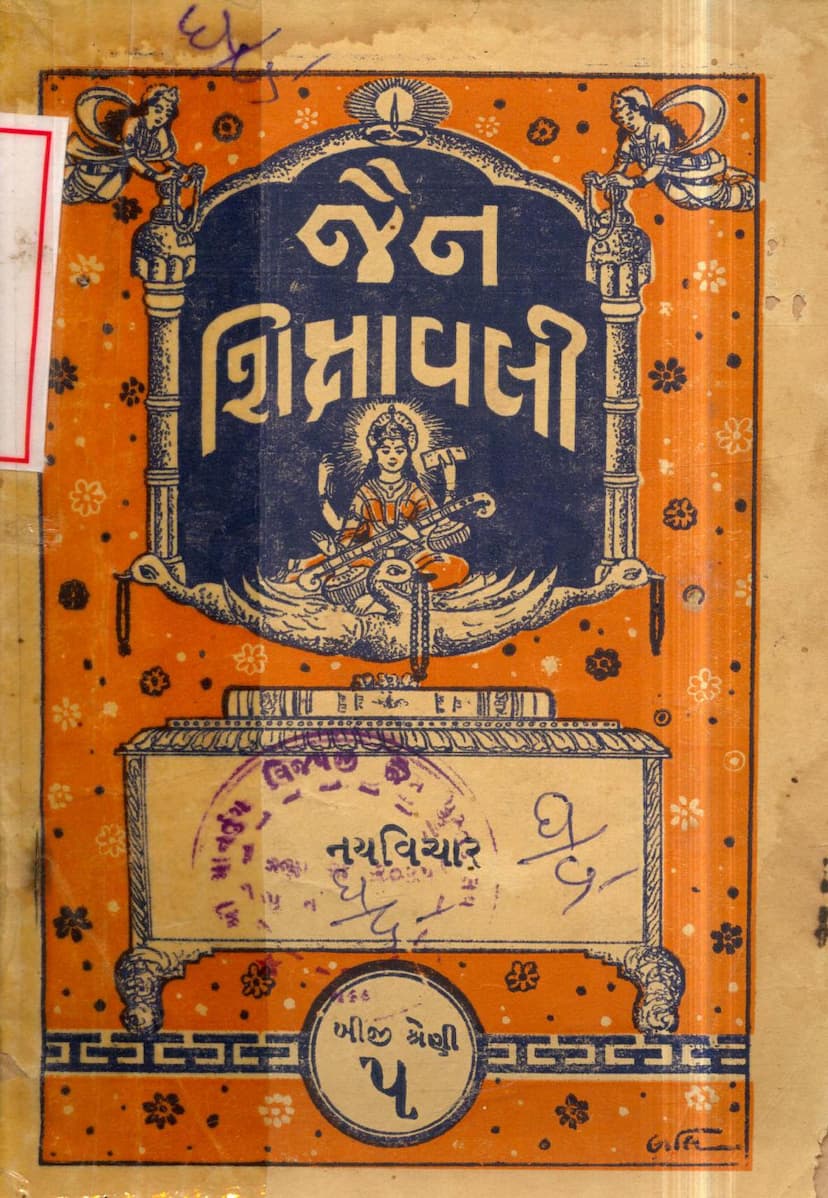

Jain Shikshavali Nayvichar

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary in English of the Jain text "Jain Shikshavali Nayvichar" by Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Jain Shikshavali Nayvichar Author: Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah Publisher: Jain Sahitya Prakashan Mandir Series: Jain Shikshavali, Second Series, Book 5

Overall Purpose: This book is a part of a series designed to educate readers about Jain philosophy and practices. This specific volume, "Nayvichar" (Discussion on Nayas), focuses on the concept of nayas (standpoints or perspectives) within Jainism, explaining their importance, types, and their relation to anekantavada (non-absolutism or manifold aspects) and syadvada (the doctrine of conditional predication).

Key Concepts and Structure:

The book systematically introduces and explains the concept of nayas through the following sections:

-

The Utility of Nayas (1-16):

- Introduction: The book begins by stating that to understand the vastness of Jain philosophy (specifically dravyanuyoga), knowledge of praman (means of valid knowledge) and naya (standpoints) is essential.

- The Frog in the Well Analogy: This analogy illustrates the limited perspective of someone who only experiences a small part of reality, comparing them to a frog in a well who cannot comprehend the vastness of a lake. This highlights the need for broader understanding, which nayas facilitate.

- The Importance of Nayas: The text emphasizes that nayas are crucial for comprehending the multifaceted nature of reality as described by Jain scholars. It quotes scriptures like the Uttaradhyayan Sutra to underscore the point that understanding all aspects of a substance requires all pramanas and nayas.

- The Principle of Relativity: Jain teachings are presented as inherently relative. Nayas are the tools that provide this relative understanding. The book asserts that without understanding nayas, one cannot grasp the true meaning of Jain teachings, as Jain sages speak from specific, relative standpoints.

- Two Travelers and the Statue Analogy: This parable vividly demonstrates the conflict arising from absolutist statements. Two travelers describe a statue's shield, one claiming it's golden, the other silver. They argue vehemently until they realize the shield is gold on one side and silver on the other. This illustrates how absolute claims without acknowledging different perspectives lead to disagreement. The text argues that statements like "This shield is golden" are nirapeksa (without relation/absolute), while "This shield is also golden" or "also silvery" are sapeksa (relative).

- The Six Blind Men and the Elephant Analogy: Similar to the travelers, this classic parable shows six blind men touching different parts of an elephant (trunk, ear, leg, tail, etc.) and describing it based on their limited experience. Each believes their description is the absolute truth, leading to arguments. The elephant keeper explains that each is partially correct, but no single description encompasses the whole elephant. This reinforces the idea that nayas help understand the complete picture by acknowledging partial truths.

- Queen Chellana's Incident: This story highlights the danger of misinterpreting words without understanding their context or the speaker's intention. Queen Chellana, feeling cold, murmurs about a meditating monk in the cold. King Shrenik overhears this and misinterprets it as her thinking about another man, leading him to order the palace to be burned. The incident is resolved when Lord Mahavir clarifies the queen's thoughts. This emphasizes that understanding the nayas (or intent) behind words is vital to avoid misunderstanding and drastic actions.

-

Definition of Naya (17-22):

- Etymology: The word naya is derived from the root ni (to lead) and signifies logic, policy, conduct, virtue, planning, method, etc.

- Jain Context: In Jainism, naya refers to the relative knowledge that helps understand a part of an object. Praman (valid knowledge) understands the whole ( sakaladesh), while naya understands a part (viklaḍesh).

- Multiple Definitions: The book provides several scholarly definitions of naya:

- Knowledge that grasps one aspect out of the infinite qualities of an object.

- That which leads or brings to one particular nature of the object, departing from other natures.

- A part of the meaning grasped by praman.

- A specific viewpoint that grasps a part of the object established by praman, remaining indifferent to other aspects.

- Infinite Aspects: The text explains that objects possess infinite qualities due to infinite possible perspectives and contexts. Analogies from poetry about the moon and photography illustrate how a single subject can be perceived and described in countless ways.

-

Nayabhasa (Pseudo-Nayas or False Perspectives) (23-24):

- Misinterpreting Nayas: When one grasps a desired aspect of an object while negating all other aspects, the resulting knowledge becomes a nayabhasa (false naya) or durnaya (wrong perspective). This is considered false or untrue knowledge.

- The Golden/Silvery Shield Revisited: The example of the shield being "only golden" or "only silvery" is again cited as a nayabhasa, as it denies the other equally valid aspect.

- The Danger of Negation: The book quotes scriptures stating that a nayabhasa is one who denies aspects other than the one grasped.

-

Synonyms for Naya (24):

- The text lists several synonyms for naya found in scriptures, such as prapaka, karaka, sadhaka, nivartaka, nirbhasaka, upalambhaka, and vyanjaka, all referring to different functions or aspects of how a naya helps in understanding.

-

Types of Nayas (24-31):

- Classification: Nayas are categorized in various ways, such as:

- Nischaya Naya (Absolute/Real Naya) and Vyavahar Naya (Conventional/Practical Naya).

- Gnan Naya (Naya of Knowledge) and Kriya Naya (Naya of Action).

- Dravyarthik Naya (Substance-oriented Naya) and Paryayarthik Naya (Mode-oriented Naya).

- Interdependence: The book stresses that Jainism advocates for the interdependence of these nayas. One cannot hold onto only nischaya or only vyavahar, for example, without losing the completeness of the doctrine. The progress of Jainism throughout history is attributed to the practical application of vyavahar naya which guides followers towards nischaya naya.

- Dravya vs. Paryaya: Dravyarthik naya focuses on the eternal substance (e.g., gold), while paryayarthik naya focuses on the changing modes or forms (e.g., ring, bracelet). Both are essential for a complete understanding. The inability to grasp substance without mode and vice-versa is explained with examples.

- Seven Nayas: The text details the seven main nayas, which are ultimately classified under Dravyarthik (Naiagam, Sangraha, Vyavahar) and Paryayarthik (Rujusutra, Shabda, Samabhirudha, Evambhuta). It notes that each naya can have hundreds of sub-types, leading to a vast system of understanding.

- The Principle of Synthesis: Jainism's strength lies in its ability to synthesize seemingly contradictory viewpoints. Just as a skilled healer can neutralize poison, syadvada integrates different nayas to reveal the true, multifaceted nature of reality.

- Classification: Nayas are categorized in various ways, such as:

-

Anekantavada and Syadvada (31-39):

- One Doctrine, Two Names: Anekantavada (non-absolutism) and Syadvada (conditional predication) are presented as two names for the same doctrine.

- Anekantavada: This doctrine asserts that reality is manifold and has infinite aspects. It counters ekantavada (absolutism), which claims only one perspective is correct. Anekantavada is applicable in both intellectual and practical spheres.

- Practical Utility: The book illustrates the practical utility of anekantavada with examples from scientific progress (like the invention of the steamship based on the understanding of iron's properties) and social behavior (treating others with consideration).

- Syadvada: This doctrine explains how to express these multiple aspects. The word "Syat" (meaning "perhaps," "in some respect," or "conditionally") is prefixed to statements to acknowledge that the assertion is true only from a particular perspective.

- Sapta-bhangi (The Seven-Fold Predication): This is the logical framework of syadvada, allowing for the expression of multiple, even seemingly contradictory, attributes of an object. The seven bhangas (predicates) are explained: asti (is), nasti (is not), asti-nasti (is and is not), avaktavya (indescribable), asti-avaktavya (is, indescribable), nasti-avaktavya (is not, indescribable), and asti-nasti-avaktavya (is and is not, indescribable). These are applied to the existence of the soul.

- Critiques and Defense: The text addresses criticisms that syadvada leads to skepticism or confusion, explaining that it is a method of comprehensive understanding, not uncertainty. It cites learned scholars who have defended syadvada against misinterpretations by other philosophical schools.

-

Opinions of Scholars on Anekanta (41-43):

- The book includes testimonials from prominent Indian scholars (Pandit Ganga Nath Jha, Anand Shankar Dhruv, Kakasaheb Kalelkar, Mysore Ruler, Pandit Hansraj Sharma, and Mahatma Gandhi) who praise anekantavada for its depth, inclusivity, and practical wisdom. Mahatma Gandhi specifically mentions how anekantavada helped him understand different perspectives.

-

Specific Nayas (43-56):

- Naiagmana Naya (The Naya of Gathering/Common Aspect): This naya acknowledges both general and specific attributes, emphasizing the interconnectedness of commonality and particularity. It considers an object as both general and specific, stating that one cannot exist without the other. Examples include understanding "human" generally and then specifically as a son, father, etc. It also discusses its subdivisions: Bhuta Naiagam (applying the present to the past), Bhavishya Naiagam (applying the present to the future), and Vartamana Naiagam (applying the present to the present).

- Jamali Muni's Heresy: This section recounts how Jamali Muni, a disciple of Lord Mahavir, fell into error by rigidly adhering to the Naiagam principle of "what is being done is done," leading him to deny the validity of certain pronouncements of Lord Mahavir and thus becoming the first schismatic.

- Sangraha Naya (The Naya of Collection/General Aspect): This naya prioritizes the general or common aspect of an object, downplaying the specific. The example of "food" encompassing various dishes illustrates this.

- Vyavahar Naya (The Naya of Practice/Specific Aspect): This naya prioritizes the specific aspects of an object, making distinctions. It argues that without specificity, clear understanding is impossible.

- Rujusutra Naya (The Naya of Straight Line/Present Moment): This naya considers only the present state of an object, disregarding past and future. It believes that past and future are irrelevant to current actions. It also emphasizes the reality of the "bhava" (quality/state) in the four nikshepas (name, establishment, substance, mode), ignoring the others.

- Shabda Naya (The Naya of Word/Meaning): This naya asserts that different words, even synonyms, might have distinct meanings based on context (time, case, gender, number, person, prefix). It signifies that the meaning of a word can change based on these factors.

- Samabhirudha Naya (The Naya of Established Meaning): This naya focuses on the conventional or established meaning of words, suggesting that synonyms like "Jin," "Arhat," and "Tirthankar" may have distinct, conventionally accepted meanings.

- Evambhuta Naya (The Naya of Being in Accordance with Name): This is the subtlest naya. It states that a word can only be applied if the object actually exhibits the quality implied by the word. For instance, "Jin" should only be used for someone actively conquering passions, "Arhat" for someone worshipped, and "Tirthankar" for someone establishing a religious order. Applying these terms otherwise is considered incorrect by this naya.

-

Naya Literature (57-58):

- A list of important Jain texts and commentaries that discuss nayas is provided for further study.

-

Conclusion (58):

- The book concludes by reiterating that nayavada is not merely an academic or argumentative topic but a systematic science for understanding the true nature of things, with significant practical utility. The author expresses a wish that readers grasp the essence of this science to achieve ultimate truth.

In essence, "Jain Shikshavali Nayvichar" serves as a foundational text for understanding the complex yet crucial doctrine of nayas in Jainism. It emphasizes that by recognizing and applying different nayas, one can achieve a more comprehensive, nuanced, and harmonious understanding of reality, thus avoiding narrow-mindedness and conflict.