Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak Khand 01 Ank 03 To 04

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This document is the third and fourth issue (Ank 3 and Anek 4) of Volume 1 of the "Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak" (Jain Literature Researcher) journal, published by the Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak Samaj, Pune, authored by Jinvijay.

Here's a comprehensive summary of its content:

Overall Focus: The journal issues focus on the preservation, research, and dissemination of Jain literature. The specific issues highlight the efforts to digitize and make accessible old and rare Jain books.

Key Sections and Content:

-

Page 1: Editorial and Sponsorship:

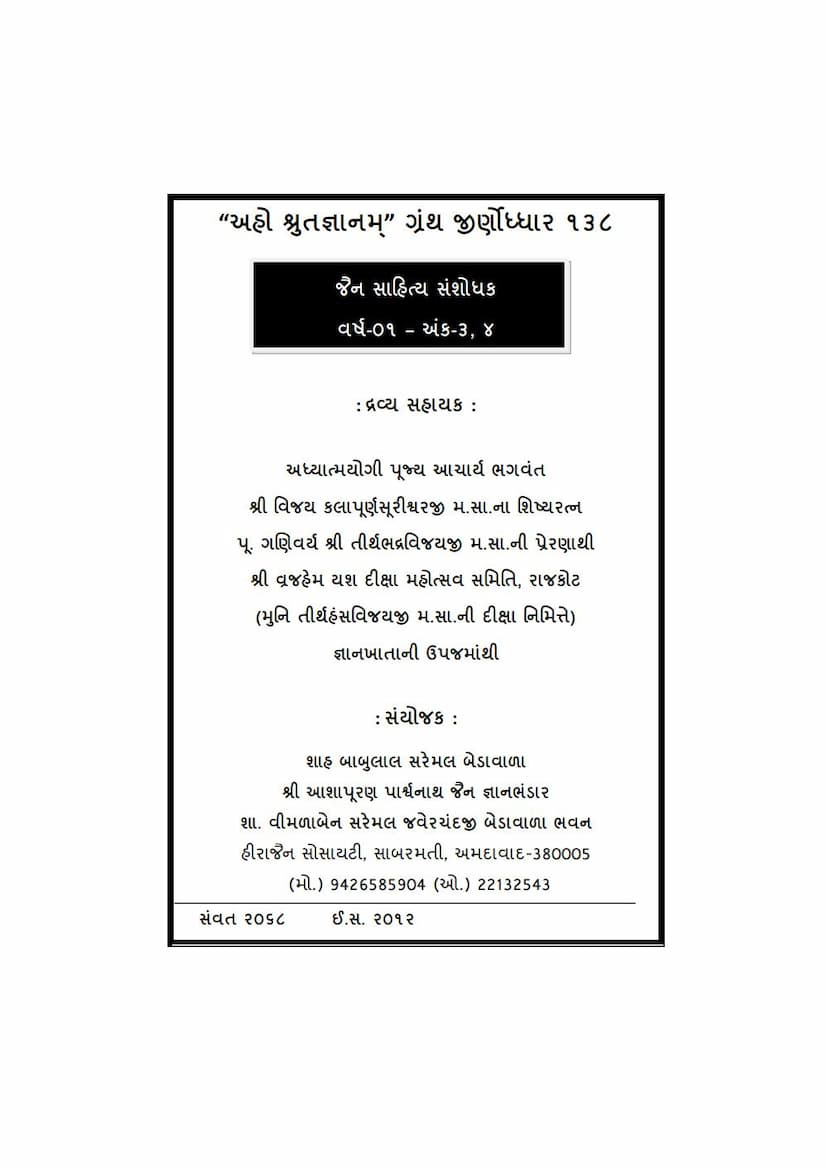

- The publication is dedicated to the "Jirnoddhar" (renovation/restoration) of the "Aho Shrutjñanam" text.

- It acknowledges the financial support from the Shri Vrajhem Yash Diksha Mahotsav Samiti, Rajkot, inspired by Pujya Ganivarya Shri Tirthbhadravijayji M.Sa.

- It lists Shah Babulal Sarumal Bedawala as the coordinator and names the Shri Ashapuran Parshwanath Jain Gyan Bhandar, Ahmedabad, as the place of operation.

- It mentions the publication year as Samvat 2068 (CE 2012).

-

Pages 2-8: List of Scanned and Digitized Rare Books:

- This is the most extensive part of the document, presenting a catalog of nearly 150 rare and hard-to-find Jain books that have been scanned and made available on DVD.

- The list is organized sequentially (1 to 153) and includes:

- Book Title: The name of the Jain text.

- Author/Commentator/Editor: The name of the person responsible for the text, its commentary, or its editing.

- Page Count: The number of pages in the book.

- Language: The language of the book (often Sanskrit, Gujarati, Hindi, or a combination).

- The catalog covers a wide range of Jain literature, including:

- Sutras and Commentaries: Nandi Sutra, Uttaradhyayan Sutra, Siddhahem (grammar and its commentaries like Brihadvrutti, Bṛhannyaas), Nyayapravesh, Tattvopanishad, etc.

- Philosophical and Logical Texts: Arhat Gita, Yukti Prakash Sutra, Manatung Shastra, Tattvoparnishinh, Vyutpatti Vada, Nyayavatara, Syadvad Ratnakara, etc.

- Works on Jain Architecture and Sculpture: Aprajitaprachha, Shilpa Smriti Vastuvidya, Shilparatnam (Parts 1 & 2), Prasada Tilak, Kashyashilpam, Prasadamajari, Rajvallabha, Shilpa Deepak, Vastusara, Diparnava, Jinprasad Martand, Shilpa Ratnakar, Prasada Mandan, Vastunighantu, etc.

- Works on Jain History and Literature: Jain Granthavali, Jain Lekh Sangrah (Parts 1-3), Jain Pratima Lekh Sangrah, Jain Chitrakalpadrum (Parts 1 & 2), Bharat ke Jain Tirth, Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak (the journal itself across different volumes/issues), etc.

- Works on Jain Rituals and Practices: Maha Prabhavik Navasmara, Pavitra Kalpasutra, Jain Stotra Sanchay, etc.

- Works on Jain Cosmology and Principles: Siddhantlakshan, Siddhanta Kaumudi (Prakrit grammar), etc.

- Works on Jain Music and Arts: Sangeet Raga Mala, Sangeet Natya Rupavali.

- Ayurvedic and Astrological Texts: Ayurvëda, Jyotish.

- Historical Texts and Inscriptions: Gujaratna Aitihasik Lekho (Parts 1-3), Bikaner Jain Lekh Sangrah, Radhanpur Pratima Lekh Sandoh, Operation in Search of Sanskrit Manuscripts.

- The listed books indicate a broad spectrum of Jain knowledge, emphasizing the extensive efforts made in their preservation and digitization.

-

Page 9: Cover Page Information:

- Confirms the title: "Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak," Vol 1, Issue 3.

- Highlights the theme: "Aho! Shrutjñanam" (Oh! Knowledge of Scriptures).

- Lists the Publisher: Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak Samaj, Pune.

- Provides contact information for Shah Baboolal Sarumal.

- Mentions the year Samvat 2068 (2012 CE).

-

Page 10: Publisher's Note/Editorial:

- Explains that the journal is not for profit but for the publication of literature.

- Acknowledges the delay in publication, comparing it to other prestigious journals like "Indian Antiquary" and "Epigraphia Indica," which also face delays.

- Mentions that the editor, Muni Jinavijayji, is based in Ahmedabad and manages two important institutions there (Gujarat Puratatva Mandir and Arya Vidya Mandir), which impacts his availability for the Pune-based journal.

- Highlights the significant size of the journal, requiring 2-2.5 months for printing.

- Mentions that due to space constraints, Hindi articles from this issue will be published in the next.

- Emphasizes the importance and rarity of a "Purani Pattavali" (old lineage document) included in this issue, noting its unique old Gujarati language and potential difficulty in initial reading but encouraging careful study.

- Asks for forgiveness from readers for the delays and expresses hope for timely publication in the future.

-

Pages 11-24: Detailed Content of "Kshetradesh Pattak" (Regional Assignment Charts):

- This section is a significant portion of the issues, presenting several historical "Kshetradesh Pattak" (regional assignment charts).

- Introduction to Kshetradesh Pattak: The editor explains what these charts are. They are orders issued by Jain Acharyas (heads of monastic orders) assigning specific monks (yatís) to particular regions or villages for their Chaturmas (four-month monastic retreat) each year.

- Historical Context: It explains that the term "yati" was used broadly for all monastic renunciates before a schism occurred approximately 250 years prior, leading to different practices. The historical context emphasizes the organized structure of the Jain monastic community, the large number of renunciates, and the authority of the Acharyas in managing them.

- Decline of Jain Society: The editor contrasts the situation 100 years prior, when villages were suitable for Chaturmas, with the present, where many villages lack even a single Jain family for a night's stay. This points to a significant decline in the Jain population and the number of renunciates. It cites Colonel Tod's Rajasthan, which mentioned 1100 Yatís of the Kharatara Gachcha alone, compared to the much smaller number today.

- Pattak 1 (Samvat 1774): This is presented in detail, listing the assignments of various monks (P. - Pandit, G. - Gani, U. - Upadhyay, S. - Shishya) to different regions like Gurjar Desh, Mewad Desh, Mewat Desh, Sorath Desh, and Kachchh Desh. It includes instructions from the Acharya (Shri Vijayksham suri) to follow the assignments, maintain decorum, and avoid disputes.

- Subsequent Pattaks (Pattak 2 to Pattak 9): These are also presented in detail, listing assignments for different years (e.g., Samvat 1822, 1823, 1824, 1837, 1866, 1880, 1882, 1903, 1908, 1911). They cover various regions and list numerous monks and their assigned locations.

- Significance: These Pattaks are valuable historical documents, providing insights into the administrative structure of Jain monastic orders, the geographical distribution of Jainism in certain periods, the hierarchy within the orders, and the social customs of the time.

-

Pages 135-140: "Sadayavatsa Savalingani Jain Katha" (The Story of Sadayavatsa and Savalingani Jain Katha):

- This is an article by the late Shri Chimanlal Dahyabhai Dalal, M.A., an esteemed scholar of Jain literature.

- It discusses the popular Gujarati story of Sadayavatsa and Savalingani, noting its widespread appeal and presence in various languages and forms throughout history, including Sanskrit, Old Gujarati, Marwadi, and Hindi.

- It traces the literary history of this story, referencing several versions by different authors and from different periods, highlighting their variations and the evolution of the narrative.

- It also touches upon the story's possible origins, potentially linked to popular tales like those of Vikramaditya.

- The narrative itself, as presented in the article, recounts the story of Prince Sadayavatsa, his marriage to Princess Savalingani, and their subsequent adventures involving palaces, curses, magical elements, and divine interventions (like Harisiddhi Mata). It includes moralistic elements and lessons related to karma and righteousness.

-

Pages 141-148: "Dr. Hermann Jacobi's Introduction to Jain Sutras" (Part 2):

- This is a continuation of an article from a previous issue.

- It focuses on the analysis of the Acharanga Sutra, describing its structure into two Shrutaskandhas, the first of which is considered the original and most ancient part.

- It discusses the prose style of the Acharanga Sutra, noting its complexity, occasional unintelligibility, and the presence of interspersed verses or stanzas, suggesting they might be quotations from other important texts.

- It delves into the nature of these prose sections, proposing that they might be collections of didactic sayings rather than a coherent logical argument.

- It highlights the presence of archaic Prakrit and occasional Sanskrit phrases, pointing to the difficulty in translation and interpretation without the aid of commentaries.

- It mentions the existence of five "Chulas" (appendices) to the second Shrutaskandha, with the fifth (Nisiijjhayana) now considered a separate text.

- It touches upon the likely older dating of the first Shrutaskandha compared to the latter parts.

- The article discusses the significant difficulty in translating and accurately conveying the original meaning of the texts, especially when dealing with technical Jain terms and archaic language, and expresses hope that future researchers will shed more light on these aspects.

-

Pages 149-157: "A Comparative Study of Uttaradhyayana Sutra with Pali Canonical Books" by Prof. P. V. Bapat:

- This article presents a comparative analysis of the Jain Uttaradhyayana Sutra and Buddhist Pali canonical books.

- Introduction: It establishes that Mahavir and Buddha were contemporaries and hence their teachings and literary expressions would likely influence each other.

- Comparisons: The study traces similarities from two perspectives:

- Matter (Content):

- Monk's General Conduct: Similarities in descriptions of a monk's patience, non-retaliation, contentment, and freedom of movement.

- Monk's Attitude towards Woman: Strict avoidance and shunning of women, considering them dangerous.

- Importance of Self-Control: Emphasis on subduing oneself being superior to conquering others.

- Miscellaneous: Parallels in general ethical principles and advice.

- Manner (Expression):

- Starting Phrases: The use of "Aho! Shrutjñanam" (Jain) and "Evam Mayaham" (Buddhist) at the beginning of texts.

- Technical Numerals: Similar use of numbered lists and technical terms (like 8 A., 6 Bhavnas, etc.).

- Phonological Features: Dropping of Anuswar (e.g., ekāṇaṁ instead of ekāṇaṁ).

- Similar Wording: Use of similar words, phrases, clusters, similes, and metaphors.

- Matter (Content):

- Conclusion: The article suggests a close proximity in thought and expression between Jain and Buddhist literature and hopes that further study will reveal more insights. It also appeals for support for Jain students to pursue comparative studies.

-

Pages 157-173: "Veer Vanshavali" (Lineage of Veer) or "Tapa Gachha Vriddha Pattavali" (Old Pattavali of Tapa Gachha):

- This section is a historical document providing a lineage of Jain Acharyas, particularly within the Tapa Gachha tradition.

- Introduction: It explains that the manuscript was provided by Shri Keshavlal Premchand Modi, B.A., LL.B. (Ahmedabad), found in the library of Pandit Shri Gulabvijayji. The manuscript dates from Samvat 1962 (approx. 1905 CE) and is a copy of an older original, whose author and exact date of creation are unknown but likely around Samvat 1806 CE, as the lineage ends with Vijaydattasuri. The author is inferred to be a follower of the Anand Suri Gachcha due to the lineage presented.

- Content: The Pattavali details the succession of Acharyas from Gautam Swami (first disciple of Mahavir), through Sudharma Swami, Jambuswami, Prabhavaswami, Shubhachandra, Haridatta, Jambukumar, Keshi, Swayambhu, Ratnaprabha, Yashobhadra, Shubhachandra, Bhadrabahu, Sthulibhadra, Mahagiri, Aryasuhasti, Shrutakevali Bhadrabahu, and many other prominent Acharyas up to the later periods (e.g., Vijaydattasuri).

- Historical Details: The text provides dates (in Vikram Samvat) for the Acharyas' succession, their gurus, notable events, disciples, and sometimes even their birthplaces or significant actions. It also includes references to historical rulers and kingdoms of the time, providing a broader socio-historical context.

- Errors and Observations: The editor notes some inaccuracies in the dates provided in the manuscript, attributing them to transcription errors or misinterpretations by the original scribe. It highlights an instance where Jagadushah, a famous philanthropist of the 14th century, is mistakenly placed in the 13th century, likely due to a confusion in the century numbers.

- Linguistic Note: The language is noted as Old Gujarati, with its original spelling and grammar preserved, even if it appears unpolished, to maintain authenticity.

-

Pages 120-134: "Bal Nyay" (Child Logic) by C. R. Jain, Bar-at-Law:

- This is an educational article aimed at introducing children (6th to 8th grade) to the principles of logic.

- Foreword: The author emphasizes the importance of "natural logic" which is inherent in humans, simple, and practical, contrasting it with complex "European logic" taught in colleges. He stresses that the failure in teaching logic lies with the instructor, not the student's capacity.

- Lessons: The article presents a structured approach to logic with specific lessons:

- Lesson 1: Deduction: Explains that deduction requires a fixed rule. Illustrations include inferring Monday from Sunday, and inferring the sex of a child (which is not possible due to lack of fixed rules).

- Lesson 2: Fixed Rules: Defines fixed rules as those that are consistently true and derived from nature or logic, not mere habit. Examples: Smoke implies fire, but fire doesn't always imply smoke.

- Lesson 3: Types of Reasoning: Introduces four types of valid reasoning (Anvaya - affirmative) and their opposites (Vyatireka - negative):

- Anvaya (Affirmative): Cause to effect, Effect to cause, Antecedent to consequent, Concomitance.

- Vyatireka (Negative): Applying the absence of the cause to infer the absence of the effect, etc.

- Lesson 4: Contradictory vs. Non-Contradictory: Explains how reasons can be contradictory (e.g., fire in a pitcher full of water) or non-contradictory.

- Lesson 5: Logic's Role: Reaffirms that logic is essential for intellectual sharpness and a successful life, lamenting its neglect in modern India and urging its teaching from childhood.

-

Pages 170-187: "Mahavir Nirvan Ka Samay Vichar" (Consideration of Mahavir Nirvana's Time):

- This is a detailed article discussing the historical debate surrounding the date of Mahavir's Nirvana.

- Traditional Jain Chronology: Mentions the widely accepted Jain calculation of Mahavir's Nirvana being 470 years before the Vikram era (527 BCE).

- Scholarly Debate: It highlights the work of scholars like Dr. Hermann Jacobi, who questioned the traditional chronology, and later Dr. F. Otto Schrader, who proposed an earlier date (467 BCE).

- Arguments and Counterarguments: The article discusses various historical and astronomical arguments used by scholars, including:

- Pattavalis and Genealogies: Analysis of succession lists and the reliability of dates mentioned.

- Buddhist Sources: Comparing Jain accounts with Buddhist texts, especially regarding the contempoary nature of Mahavir and Buddha. It notes that Buddhist texts often depict Mahavir's followers in contrast to Buddha's.

- Royal Genealogies: The importance of royal lineages like Maurya and Shunga for historical dating.

- Astronomical Calculations: The use of astronomical data to verify historical dates, particularly the conjunctions of stars and planets during important events.

- Inscriptions: The significance of inscriptions like the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela, which provides crucial chronological data.

- Dr. Jacobi's Contribution: The article highlights Dr. Jacobi's detailed analysis and his conclusion that while Jain tradition is ancient, the specific dates might need revision. His work often contrasts Jain claims with Buddhist or Brahmanical sources.

- Shri Jayaswal's Contribution: It prominently features the work of Shri Jayaswal, who analyzed the Hathigumpha inscription and argued for a revised date for Mahavir's Nirvana around 488 BCE, correcting the 470-year difference by reinterpreting the starting point of the Vikram era. His work is presented as a significant step in reconciling historical and traditional accounts.

- Conclusion: The article emphasizes the complexity of establishing precise historical dates for ancient India and acknowledges the ongoing scholarly debate, suggesting that a comprehensive understanding requires considering multiple sources and methodologies.

-

Pages 188-198: "An Historical Letter":

- This section presents a very old letter (Samvat 1831 / 1774 CE) written in a mix of Rajasthani (Mewari dialect) and Gujarati.

- Content: The letter is from a Jain monk, Rishabhvijayji, to a respected elder (Panditji) at Nathdwara, Rajasthan. It vividly describes the political and social turmoil in Mewar and surrounding regions during that period.

- Historical Details: The letter paints a picture of:

- Political Instability: Frequent conflicts between rulers like Rana Hamir Singh of Mewar and other regional powers like the Rana of Dhod, battles between Rajput clans (Chouhan, Bhati, Solanki), and the presence of Mughal forces (from Delhi and Agra).

- Economic Hardship: Mention of famine, high taxes, and the devaluation of currency (Taka).

- Monastic Life: The monk's own journey, his experiences, and his concern for the safety of the monastic community amidst the political unrest. He mentions being unable to reach his intended destination due to the volatile situation.

- Social Context: It highlights the role of religious figures in disseminating news and information in the absence of modern communication.

- Significance: This letter is a valuable primary source for understanding the socio-political conditions of Rajputana in the late 18th century, particularly from the perspective of a religious traveler.

-

Pages 190-217: "Detailed Pattak Lists" (Kshetradesh Pattak):

- This section contains numerous lists of Jain Acharyas and the regions they were assigned to for Chaturmas. These are the "Kshetradesh Pattak" mentioned earlier.

- Pattak 1 (Samvat 1774): This is the "oldest" Pattak presented, detailing assignments for Mewar and surrounding areas, listing 17 monks.

- Subsequent Pattaks (Pattak 2 to 9, and others up to Pattak 20, and even more in the pages that follow): These are lists for different years, some dating back to the 17th century (Samvat 1667) and going up to the 19th century (Samvat 1882, 1903, 1908, 1911). They list hundreds of names of monks and their assigned locations across various regions of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and parts of Western India.

- Significance: These detailed lists are crucial for historical research on the Jain monastic system, its geographical spread, the names of prominent Acharyas and monks, and the administrative structure of the Gachchas (monastic orders). They offer invaluable data for scholars studying Jain social history, demography, and the evolution of monastic practices.

-

Pages 218-222: "Mahavir Tirthkar ni Janmabhumi" (Birthplace of Mahavir Tirthkar):

- This article discusses the birthplace of Lord Mahavir.

- Traditional View: Mentions the traditional Jain belief that Mahavir was born in Kundagram/Kundapur, considered a part of Vaishali, ruled by King Siddharth.

- Scholarly Debate: It contrasts this with the view of Western scholars like Dr. Hermann Jacobi and Dr. Hornle, who suggest that Kundagram was a mere village near the larger city of Vaishali, and that the traditional beliefs might be embellished.

- Evidence: It references archaeological findings and textual interpretations from Jain and Buddhist scriptures to support or refute these claims, discussing the significance of names like Vaishali, Koshala, and Kunnagar.

- Conclusion: The article highlights the ongoing debate and the challenges in definitively pinpointing the exact birthplace, considering the mythological and historical layers in the narratives.

-

Pages 223-230: "Ahimsa ane Vanaspati Ahar - Khas Karine Bauddha Dharma" (Ahimsa and Vegetarian Diet - Especially in Buddhism):

- This article, translated from Dr. F. Otto Schrader, compares Jain and Buddhist views on Ahimsa (non-violence) and vegetarianism.

- Jain Ahimsa: Emphasizes the strictness of Jain Ahimsa, extending to all forms of life, including plants (microscopic beings), and the detailed rules for monks and laypeople to avoid causing harm. It highlights the concept of trividha aparigraha (non-possession of three types of things) and the meticulousness of Jain practices to minimize harm.

- Buddhist Ahimsa: Discusses Buddhist perspectives on Ahimsa, noting that while vegetarianism was encouraged for monks, it was not always strictly enforced, especially for lay followers. It touches upon the interpretation of "upasaka" (lay follower) rules and the nuances in Buddhist texts regarding the consumption of meat, particularly the concept of "pure meat" (trilalaviddhamamsa).

- Comparison: The article points out similarities in the underlying principles of non-violence but highlights the difference in the degree of strictness. Jainism generally adheres to a more comprehensive and strict form of Ahimsa, including strict vegetarianism, while Buddhism allowed for more flexibility, especially for lay followers, and had specific rules regarding "pure meat."

- Debate on Buddha's Diet: It mentions the scholarly debate regarding whether Buddha himself was a vegetarian, with some interpretations suggesting he was and others allowing for the possibility of his consuming meat under specific conditions.

- Criticism of Buddhist Interpretations: The author, quoting Schrader, notes that some interpretations of Buddhist texts might misrepresent Jain principles or inflate Buddhist concessions for the sake of creating a favorable comparison.

-

Pages 231-246: "Veer Vanshavali" (Lineage of Veer) or "Tapa Gachha Vriddha Pattavali" (Old Pattavali of Tapa Gachha):

- This section is the continuation and a significant part of the "Veer Vanshavali" or "Tapa Gachha Vriddha Pattavali" mentioned earlier.

- It continues to list the succession of Jain Acharyas, their lineages, birthplaces, dates of succession, notable events, and sometimes their literary contributions.

- It traces the lineage through various Gachchas like Tapa Gachha, Anand Gachcha, Kharatara Gachcha, and others, mentioning prominent Acharyas like Hemchandracharya, Ratnasekhar Suri, Udyotan Suri, and many more.

- The detailed accounts provide rich historical information about the spread and development of Jainism in different regions, the administrative structure of monastic orders, and the interrelationships between various Gachchas and historical rulers.

- It also includes references to legendary figures and events, highlighting the blend of history and tradition in the compilation.

-

Pages 247-250: "Aagra Sanghano Savatsarik Patra" (Savatsarik Letter from Agra Sangh):

- This section contains a facsimile of a historical letter written in a mixed Hindi-Gujarati script from the Agra Jain Sangh to an Acharya.

- Content: The letter describes the political situation in Rajasthan, with references to the Mughal Emperor Jahangir's orders and the impact of political instability on the Jain community. It details local events, the activities of monks, and expresses devotion to the Acharya.

- Socio-Political Context: The letter provides insights into the interaction between the Jain community and the ruling powers, the influence of monastic leaders, and the challenges faced by religious communities during periods of political upheaval.

- Visual Representation: The inclusion of the original letter's script (though somewhat damaged) adds significant historical value.

-

Pages 251-252: Index:

- This is a table of contents for the entire volume, listing all the articles and their page numbers.

Overall Significance:

These issues of "Jain Sahitya Sanshodhak" serve as a vital resource for researchers and enthusiasts of Jain history, literature, philosophy, art, and architecture. The detailed catalog of digitized books underscores a significant effort in preserving Jain heritage. The inclusion of historical documents like the "Kshetradesh Pattak" and the "Veer Vanshavali" offers invaluable primary source material, while the scholarly articles like the comparative study and the analysis of Mahavir's Nirvana date contribute to a deeper understanding of Jainism's historical context and its intellectual traditions. The dedication to making rare texts accessible is a commendable effort in promoting Jain studies globally.