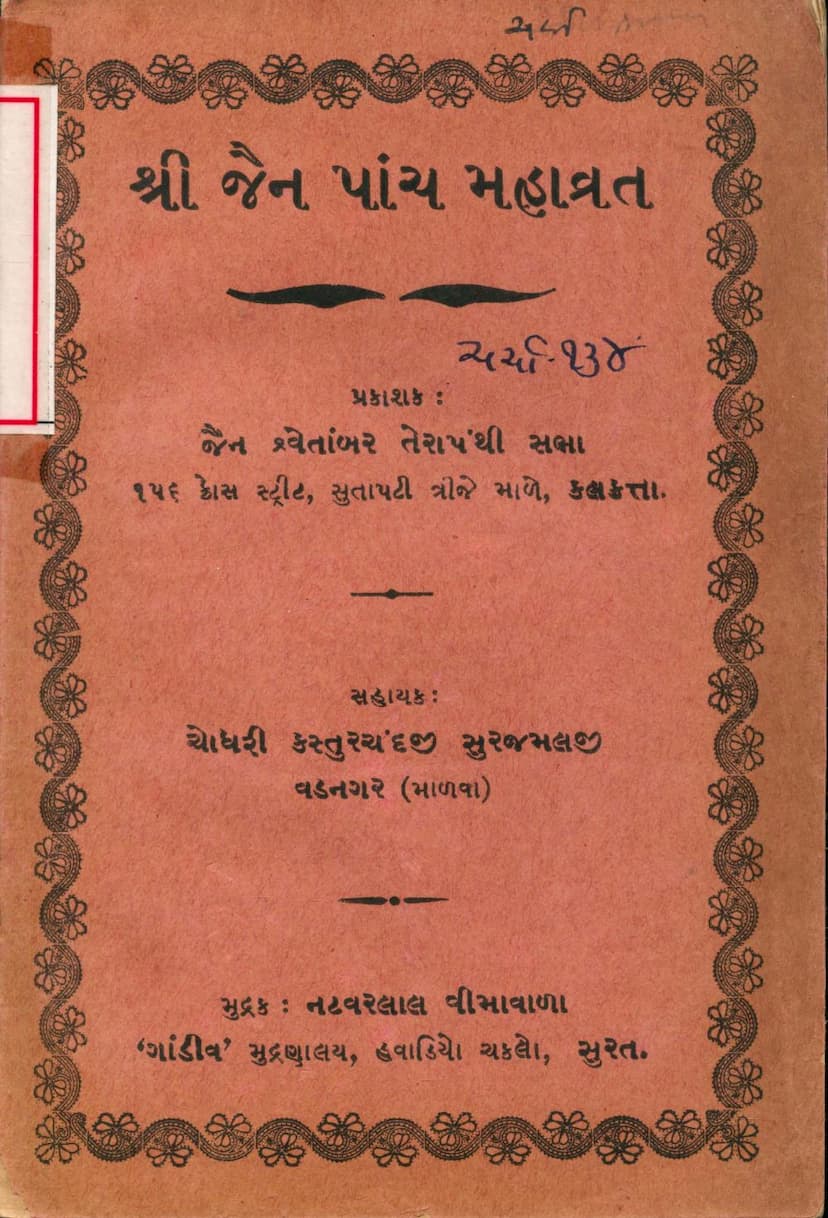

Jain Panch Mahavrat

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jain Panch Mahavrat" by the Jain Shwetambar Terapanthi Sabha delves into the core principles of Jainism, specifically focusing on the "Five Great Vows" (Panch Mahavrat). The book, published by the Jain Shwetambar Terapanthi Sabha, serves as an educational resource explaining these fundamental ethical guidelines for followers of Jainism, particularly within the Terapanth tradition.

Key Themes and Concepts Explained:

The text systematically explains each of the Five Great Vows, elaborating on their meaning, implications, and practical application, especially for monks and nuns. It also touches upon related concepts like the "Thirteen Principles" (13 Bel), which include the Five Great Vows, Five Samitis (careful conduct), and Three Guptis (restraint).

The Five Great Vows (Panch Mahavrat):

-

Ahimsa (Non-violence): This is presented as the paramount vow, the "supreme dharma" (pardharma). The text details the absolute and exhaustive nature of this vow for ascetics, extending to all six types of living beings (Jiv) and encompassing all nine categories (nav koti) of violence:

- Three Kinds of Actions: Mind, speech, and body.

- Three Modes of Action: Committing, causing to commit, and consenting to (approving) an action.

- Nine Categories of Violence: The text explains how these three modes applied to each of the three actions (mind, speech, body) result in nine ways of abstaining from violence.

- Six Types of Living Beings (Chha Kaya): The text meticulously defines each:

- Prithvikaya: Earth-bodied beings (soil, minerals, gems).

- Apkaya: Water-bodied beings (water bodies).

- Teukaya: Fire-bodied beings (fire, heat).

- Vayukaya: Air-bodied beings (air).

- Vanaspati Kaya: Plant-bodied beings (plants, fruits, leaves).

- Traskaya: Mobile beings (insects, animals, humans).

- The text emphasizes that monks are considered fathers to these six types of beings and must not cause them harm, even for the perceived greater good of mobile beings. It uses analogies from scripture, like the story of Gautam Swami questioning Lord Mahavir, to illustrate how even sensory perception of suffering is a basis for non-violence. The concept of punya (merit) is also discussed in relation to protecting all living beings.

-

Satya (Truthfulness): The vow of truthfulness is explained as absolute and unwavering, even in difficult situations.

- Nine Categories of Abstinence: Similar to Ahimsa, the vow against falsehood is understood across nine categories (mind, speech, body, and their modes of commission).

- Situational Ethics: The text addresses the common dilemma of whether to speak a falsehood to save a life, citing scriptures like Acharanga Sutra to emphasize that remaining silent is preferred over lying. It explains that even a seemingly harmless lie constitutes a breach of the vow.

-

Asteya (Non-stealing): This vow prohibits taking anything that is not freely given.

- Two Types of Stealing:

- Sachet (Living): Taking living beings, such as disciples without proper consent from their families. The text stresses the need for proper understanding of Jain principles and adherence to rules before initiation.

- Achet (Non-living): Taking inanimate objects like food, water, clothes, or books without permission.

- Strict Adherence: The text warns against the repercussions of violating this vow, including the loss of one's monastic status and the potential for punishment.

- Two Types of Stealing:

-

Brahmacharya (Chastity/Celibacy): This vow encompasses strict control over sensual desires and actions.

- Three Types of Improper Conduct (Kushil): Related to deities, humans, and animals.

- Prohibitions: The vow extends to any interaction with women, even those who are physically impaired, to avoid any suspicion or violation of celibacy.

- Discipline and Moderation: The text highlights the importance of maintaining boundaries and the necessity of regulated consumption and behavior to uphold this vow. It mentions the practices of esteemed monks like Acharya Shri Bhikhanji Swami and Shri Jitamalji Maharaj in establishing such guidelines.

-

Aparigraha (Non-possession/Non-attachment): This vow deals with limiting one's possessions and attachments to material things.

- Nine Types of Possessions: The text lists and explains: Hiranya (silver/money), Suvarna (gold), Dhana (wealth/grains), Kshetra (land), Vastra (clothes), Patra (utensils), Dwipad (two-footed beings – servants/disciples), Chaupad (four-footed beings – animals), and Kumbhi Dhatu (metals like copper, brass).

- Detailed Prohibitions: The text meticulously outlines what is forbidden for monks, including:

- Possessing money, even for postage (stamps, envelopes) as it is considered a form of currency.

- Engaging in postal correspondence due to the associated attachment and potential for breaking other vows (e.g., travel by train, requesting favors from householders).

- Accepting donations for printing books or establishing libraries, as this constitutes collecting possessions.

- Maintaining strict limits on clothing (three pieces) and utensils (three pieces), as defined in scriptures like Vyavahar Sutra and Acharanga Sutra.

- The text also clarifies that even possessions meant for ascetic use should not be "established" or designated permanently, emphasizing the importance of detachment and flexibility.

- It discusses the issue of hired individuals or servants and the principle of not utilizing them for personal gain.

- The text strongly condemns encouraging others to acquire animals like cows for religious merit, as this constitutes attachment.

- The use of glasses (spectacles) is debated, with scripture prohibiting the possession of items made of glass or metal, even if for the purpose of enhancing knowledge. The text emphasizes adherence to the Lord's commands over personal interpretations.

Thirteen Principles (13 Bel):

Beyond the five Mahavratas, the text elaborates on the Five Samitis and Three Guptis, collectively known as the Thirteen Principles. These are essential for disciplined monastic life:

-

Five Samitis (Careful Conduct):

- Irya Samiti: Careful movement, ensuring no harm to living beings while walking.

- Bhasha Samiti: Careful speech, speaking truthfully and without causing harm.

- Eshana Samiti: Careful begging for alms, ensuring purity and avoiding the 42 defects and 52 improper actions. The text details these defects with extensive lists and scriptural references.

- Adana Nikshepana Samiti: Careful handling of objects, ensuring proper placement and retrieval.

- Uchchara Pasravana Samiti: Careful excretion and urination, ensuring minimal harm to living beings.

-

Three Guptis (Restraint):

- Man Gupiti: Restraint of the mind from evil thoughts.

- Vachan Gupiti: Restraint of speech from uttering harmful words.

- Kaya Gupiti: Restraint of the body from performing unrighteous actions.

The Significance of Terapanth:

The text explains the meaning of "Terapanth," clarifying that it signifies "Your Path" (Tera = yours, Panth = path). It emphasizes that the path belongs to the Lord, not to any individual, and those who strictly follow the Lord's teachings (the thirteen principles) are part of this path. The name is considered universal and impartial.

Addressing Skepticism about Modern Practice:

A significant portion of the book addresses the common doubt that adhering to these strict vows might be impossible in the current era (fifth era). The text refutes this by referencing scriptures that predict the continuation of the Lord's teachings throughout the fifth era and by citing historical examples of ascetics who maintained strict adherence to vows even in challenging times. It argues that the current era requires even more stringent adherence due to inherent inclinations towards laxity.

The Importance of Correct Guidance:

The book strongly emphasizes the need for discernment in choosing a spiritual guide. It warns against following those who merely wear the ascetic robes but do not strictly uphold the vows. True gurus, according to the text, are those who embody the principles and guide disciples in the right direction. The text provides criteria for identifying a true guru and encourages followers to question and verify the conduct of their spiritual teachers.

Conclusion:

"Jain Panch Mahavrat" is a detailed and authoritative guide that elucidates the fundamental ethical framework of Jainism, particularly for those committed to a monastic life within the Terapanth tradition. It serves as a vital resource for understanding the depth and rigor of these vows, urging adherents to strive for their complete and unwavering observance. The text also aims to clarify the principles of the Terapanth path and guide individuals in discerning true spiritual teachers.