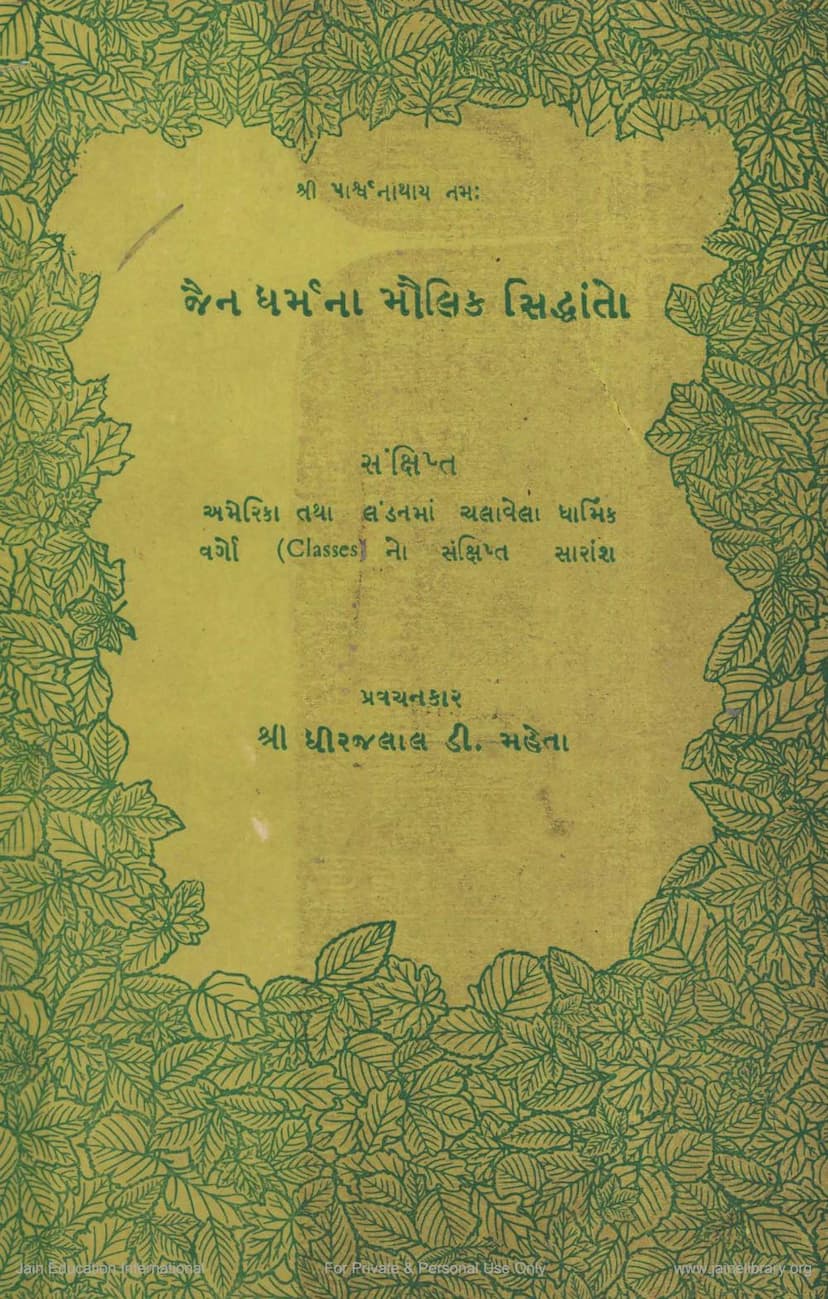

Jain Dharma Na Maulik Siddhanto

Added to library: September 2, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jain Dharma na Maulik Siddhanto" by Dhirajlal D Mehta, based on the provided pages. The book is essentially a compilation of lectures given by the author in America and London in 1991 and 1992, aimed at explaining the fundamental principles of Jainism to a broader audience.

Overall Purpose and Structure:

The book aims to elucidate the core tenets of Jainism in a way that is accessible to those who may not have deep prior knowledge. It covers essential concepts that strengthen faith and lead to right understanding (Samyak Darshan). The structure is based on five main topics:

- Navkar Mantra to Samayika: Explaining the foundational mantras and practices.

- Navatattva: The nine fundamental realities or categories.

- 14 Gunasthanaka: The fourteen stages of spiritual development.

- Karma Sambandh Charcha: Discussion on the nature of karma.

- Anekantavada and Syadvada: The Jain philosophy of manifold perspectives and conditional predication.

Additionally, the book includes a glossary of difficult terms in simple Gujarati.

Key Concepts and Chapters (as detailed in the provided pages):

The book systematically breaks down these core principles:

Chapter 1: Navkar Mahamantra to Samayika Sutra (Page 6-17)

- Jainism's Eternity: The text emphasizes that Jainism is an eternal religion, not founded by specific Tirthankaras but rather revealed by them. Tirthankaras (like Rishabhdev, Parshvanath, Mahavir Swami) are those who attain omniscience and show the path to liberation. Jainism is an independent and true path, not a branch of any other religion.

- Panch Parmeshthi (Navkar Mantra):

- Arihant: Those who have conquered inner enemies like passion and hatred, possess omniscience and perception. The text distinguishes between the Niruktarth (conqueror of enemies) and Vyutpattiarth (worthy of infinite virtues).

- Siddha: Souls who have attained liberation after shedding all karmas, residing in the Siddhashila. They are formless and eternal.

- Acharya, Upadhyay, Sadhu: These are the human guides (Gurus) who follow the teachings of the Arihants and Siddhas. The text explains their roles: Acharyas (leaders of the monastic order), Upadhyays (teachers of scriptures), and Sadhus (ascetics devoted to self-realization).

- Hierarchy and Gratitude: While Siddhas are in a higher state, Arihants are revered first in the Navkar Mantra because their teachings are the source of liberation.

- Qualities of Parmeshthis: The book outlines the 108 qualities associated with the Panch Parmeshthis, with specific numbers assigned to each (Arihant - 12, Siddha - 8, Acharya - 36, Upadhyay - 25, Sadhu - 27).

- The Significance of the Namaskar: The namaskar is considered Bhavamangal (internal auspiciousness) that destroys sins and leads to eternal happiness, unlike material auspiciousness (like Akshat, Shrifal).

- Understanding the Soul and God: The book clarifies that God is not a creator but an exemplified soul that has attained perfection. Souls are independent and eternal, and can attain the state of Siddhas through their own efforts.

- The Lok and its Inhabitants: The universe (Lok) is explained, and the concept of souls residing in it. The idea of merging with a universal God is refuted; instead, liberated souls remain distinct yet reside in the same space.

- Samyika (Equanimity): The practice of Samayika, a period of equanimity, is described as a crucial practice for householders to emulate the monastic life, aiming for mental stillness and detachment.

- Panchindriya Sanvarana (Control of the Five Senses): The text details how controlling the senses is vital for spiritual progress, linking the control of each sense to the service of the corresponding Parmeshthi.

- Nav Brahmacharya Gupta (Ninefold Observances of Chastity): Strict guidelines are given to maintain purity and prevent lustful thoughts, illustrating the high moral standards.

- Chaturvidha Kashaya Mukti (Freedom from Four Types of Kashayas): The text explains the destructive nature of anger, pride, deceit, and greed, and how to overcome them.

- Panch Mahavratas (Five Great Vows): The vows of non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, celibacy, and non-possessiveness are explained as the foundation of monastic conduct.

- Panchachara (Fivefold Conduct): Knowledge, Perception, Conduct, Austerity, and Virya (Energy) are described as the essential conduct for spiritual advancement.

- Pancha Samiti and Tri Gupta (Fivefold Conduct and Threefold Restraints): Detailed explanations are given for the five careful activities (Samitis) and the three restraints (Guptis) that govern the actions of ascetics.

- Ichchhami Khama Samano Sutra (Guru Vandana): This section explains the reverence for Gurus and the importance of asking for forgiveness before undertaking religious practices.

- Iriyavahiya Sutra and Tassuttari Sutra: These sutras are described as means for purification, seeking forgiveness for unintended harm to living beings during movement and speech, and for further spiritual cleansing. The importance of vegetarianism and avoiding meat is strongly emphasized.

- Kayotsarga (Self-Mortification/Stillness): This practice, performed for purification and penance, is explained along with the concept of 'Aagar' (permission for natural bodily functions during Kayotsarga).

- Logassa Sutra (Praise of the 24 Tirthankaras): This section describes the praise of the Tirthankaras who established the Jain order and are seen as guides across the cycles of time (Utsarpini and Avsarpini).

- Karemi Bhante Sutra (Samayika Pledge): This is a core formula for initiating Samayika, emphasizing the renunciation of sinful activities and commitment to spiritual practice.

Chapter 2: Navatattva (The Nine Truths) (Page 37-50)

- Jiva and Ajiva: The fundamental distinction between the living (Jiva) and the non-living (Ajiva).

- Jiva: Characterized by consciousness and knowledge, souls are eternal, independent, and not created by any external deity. They are embodied and pervade their bodies.

- Types of Jivas: Classified based on the number of senses: Ekendriya (one-sensed), Vikaleindriya (two- to four-sensed), and Panchindriya (five-sensed). The text elaborates on the five types of Ekendriyas (Earth-bodied, Water-bodied, Fire-bodied, Air-bodied, and Plant-bodied).

- The Cycle of Rebirth: The concept of transmigration between different realms (hell, animal, human, divine) is discussed, emphasizing that any soul can move between these realms.

- The Nature of Hell and Heaven: These realms are explained as consequences of karmic actions, not as places of eternal reward or punishment.

- Ajiva (Non-living): The five categories of Ajiva are explained:

- Dharmastikaya, Adharmastikaya, Akashastikaya: Substances that facilitate movement, rest, and space respectively, existing only within the Lok (universe).

- Pudgalastikaya: Matter, which is composed of atoms and is the basis of physical existence, including the eight types of Varganas (categories of matter) that form bodies, speech, mind, and karma.

- Kala (Time): Considered a substance in Jainism, though often seen as a flux or mode of existence.

- Punhya and Pap (Merit and Demerit): The karmic consequences of actions, leading to happiness (Punhya) and suffering (Pap). The text lists 42 types of merit-producing karmas and 82 types of demerit-producing karmas. The concept of Anubandhi (connections) is introduced, explaining how meritorious acts can lead to further merit or demerit, and vice-versa.

- Asrava (Influx of Karma): The channels through which karmas enter the soul, primarily driven by the senses, passions, and actions.

- Samvara (Stoppage of Karma): The means to prevent the influx of new karmas, achieved through controlling senses, passions, and actions. This section details the 5 Samitis, 3 Guptis, 10 Yati-dharmas (virtues for ascetics), 12 Bhavanas (contemplations), 22 Parishahas (endurances), and 5 Charitras (conducts).

- Nirjara (Shedding of Karma): The process of eradicating existing karmas, primarily through austerities (Tapas), both external and internal.

- Bandha (Bondage of Karma): The process by which karmic particles attach to the soul due to passions and actions. The text explains the four types of bondage: Prakriti (type), Sthiti (duration), Rasa (intensity), and Pradesha (quantity).

- Moksha (Liberation): The ultimate goal of Jainism, the state of the soul when all karmas are destroyed, leading to omniscience, infinite bliss, and eternal existence at the apex of the universe. The book discusses the process of attaining Moksha and the various types of liberated souls.

Chapter 3: 14 Gunasthanaka (Stages of Spiritual Development) (Page 64-76)

- The Progression of the Soul: This chapter details the fourteen stages of spiritual progress, starting from Mithyadrushti (wrong belief) and progressing through various stages of partial and full spiritual development, culminating in Moksha.

- Karanas (Processes): The three crucial processes (Yathapravritta, Apurva, Anivartika) that lead a soul from delusion to right belief are explained.

- Types of Samyakdarsan: The three types of right perception (Upashama, Kshayosapama, Kshayika) are described in relation to the Gunasthanas.

- Vow-taking: The stages involving the adoption of minor vows (Anuvratas) by householders and major vows (Mahavratas) by ascetics are outlined.

- The Path to Omniscience: The chapter progresses through the stages of partial omniscience (Sayogi Kevali) and culminates in the state of omniscience (Ayogi Kevali), leading to liberation.

- The Nature of Karma and its Shedding: The Gunasthana progression is intrinsically linked to the modification and eventual shedding of karmas.

Chapter 4: Karma Sambandh Charcha (Discussion on Karma) (Page 77-104)

- The Role of Karmas: This section delves deeper into the eight types of karmas (Jnana-avaraniya, Darshana-avaraniya, Vedaniya, Mohaniya, Ayushya, Nama, Gotra, Antaraya) and their classifications.

- Binding Causes: The text reiterates the four main causes of karmic bondage: Mithyatva (false belief), Avirati (non-restraint), Kashaya (passions), and Yoga (activities of mind, speech, and body).

- Detailed Karma Descriptions: Each of the eight karmas is explained in detail, including:

- Jnana-avaraniya (Knowledge-obscuring): How it obstructs the soul's innate knowledge.

- Darshana-avaraniya (Perception-obscuring): How it obstructs the soul's innate perception. The text differentiates between general perception (Darshan) and specific knowledge (Jnana).

- Vedaniya (Feeling): Karma that results in pleasant (Sata) or unpleasant (Asata) feelings.

- Mohaniya (Delusion): Karma that creates attachment and aversion, clouding judgment. This is further divided into Darshan Mohaniya (affecting right belief) and Charitra Mohaniya (affecting right conduct).

- Ayushya (Lifespan): Karma that determines the duration of life in a particular existence.

- Nama (Body-determining): Karma that shapes the physical form, senses, and qualities. This is extensively detailed with classifications like Pind Prakriti and Pratyek Prakriti.

- Gotra (Status-determining): Karma that influences one's birth into higher or lower social strata.

- Antaraya (Obstruction): Karma that blocks the soul's inherent qualities like generosity, gain, enjoyment, etc.

- The Mechanics of Karma: The text explains how karmas are bound, how their duration, intensity, and quantity are determined, and how they can be modified through various processes (Sankraman, Udartana, Apavartana, Udhirana, Upashama, Nidhriti, Nikachana).

Chapter 5: Anekantavada and Syadvada (Page 105-114)

- The Doctrine of Manifold Aspects: This chapter explains the philosophical cornerstone of Jainism – Anekantavada, the principle that reality has multiple facets, and Syadvada, the doctrine of conditional predication (speaking from a particular perspective).

- Nitya and Anitya (Eternal and Transient): The concept that all substances have both an eternal (Dravya) and a transient (Paryaya) aspect is central. The example of gold transforming from a bracelet to an earring illustrates this.

- Rejection of Absolutism: Jainism critiques other philosophical schools for their "ekantavada" (one-sided views), emphasizing that a complete understanding requires considering multiple perspectives.

- The Blind Men and the Elephant Analogy: This classic parable illustrates how each perspective, though incomplete, contributes to a fuller understanding of the whole.

- The Seven Nayas (Perspectives): The seven modes of understanding reality are introduced (Naigamanaya, Sangrahanaya, Vyavaharana, Rujusutranaya, Shabdhanaya, Samabhirudhanaya, Evambhutaanaya), highlighting how different viewpoints lead to different valid conclusions.

- The Five Samavayi Karana (Concurrent Causes): The idea that every effect arises from the interplay of five factors: Time, Nature, Destiny, Karma, and Effort. The text critiques the overemphasis on any single factor, advocating for a balanced approach where human effort (Purushartha) is emphasized for spiritual growth.

Glossary (Page 115-148):

The book concludes with a detailed glossary of Gujarati terms with their meanings, making it easier for readers to comprehend the philosophical and religious vocabulary.

Overall Tone and Audience:

The author's tone is didactic and encouraging, aiming to educate and inspire readers towards spiritual progress. The book is written in accessible Gujarati, with the glossary aiding understanding, making it suitable for a broad audience interested in Jain philosophy. The introductory note about the lectures in America and London suggests a desire to spread Jain teachings globally.