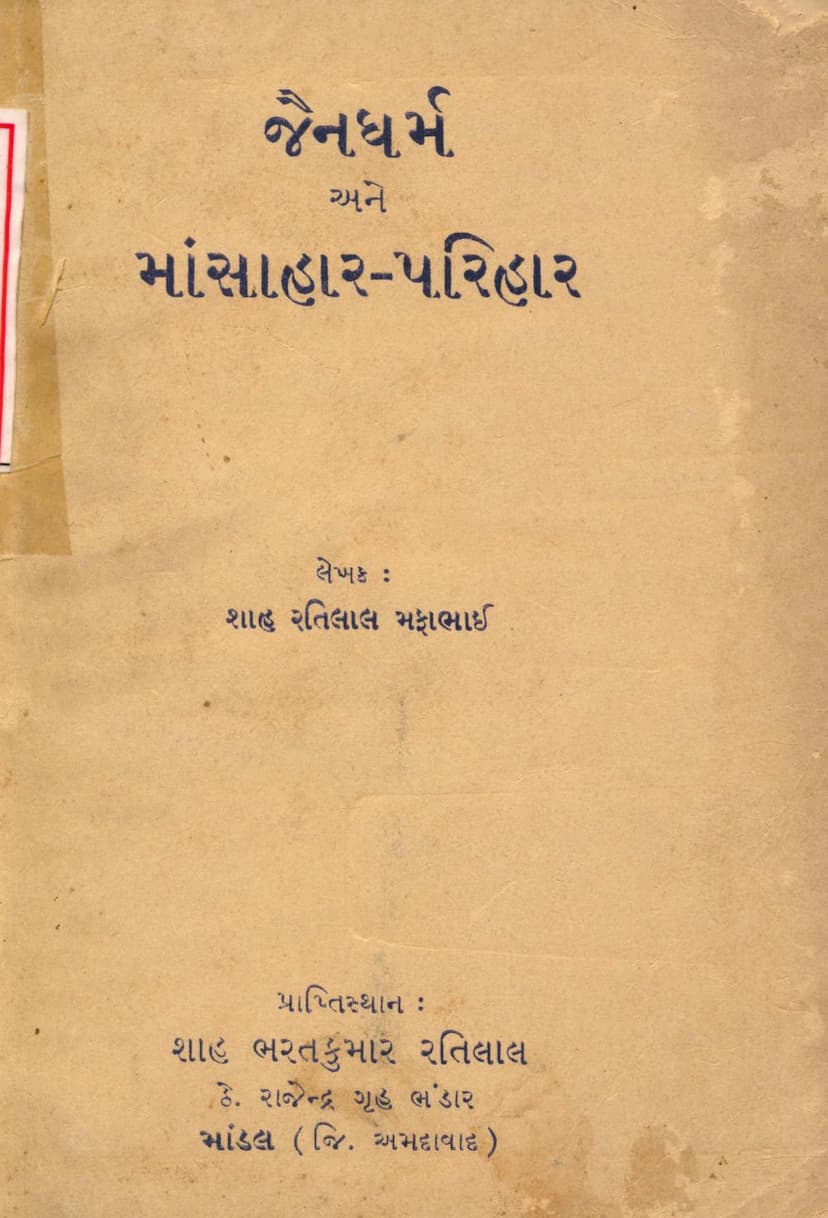

Jain Dharm Ane Mansahar Parihar

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jain Dharm Ane Mansahar Parihar" by Ratilal Mafabhai Shah, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Jain Dharm Ane Mansahar Parihar (Jainism and the Avoidance of Non-vegetarianism) Author: Ratilal Mafabhai Shah Publisher: Ratilals Mafabhai Shah Publication Year: 1967 (VS 2023) Price: Two and a half rupees

Core Argument and Purpose: The book aims to address and clarify the complex issue of meat-eating (mansahar) within Jainism, particularly in relation to Lord Mahavir. The author's primary goal is to present a historically and contextually accurate understanding of the scriptures, arguing against the interpretation that Jain scriptures permit or even describe meat-eating by Tirthankaras or their followers in a positive light. The author believes that seemingly problematic passages are either misunderstandings of ancient language, context-specific exceptions during dire times, or later interpolations. The book seeks to defend the purity and integrity of Jain principles, especially Ahimsa (non-violence), and highlight the glorious, albeit often misunderstood, history of Jainism.

Key Themes and Chapters (as per the index):

-

Introduction (Vishayaram): The author sets the stage by stating his intention to research the topic of meat-eating in Jainism with an open mind, free from prejudice. He refers to his previous book, "Bhagwan Mahavir ane Mansahar," and emphasizes the need for clarification due to scholarly debates.

-

Suspicious Passages (Shankaspad Patho): This section is crucial as it delves into specific verses from Jain scriptures (like Dashavaikalik, Acharaanga, and Bhagavati Sutra) that have been interpreted by some scholars to suggest meat-eating. The author intends to analyze these passages critically.

-

Commentaries of Acharyas (Acharyoni Tikao): The author examines the interpretations provided by prominent Jain commentators like Haribhadrasuri and Shilaankacharya, noting how their interpretations might have contributed to the controversy and exploring the reasons behind their views.

-

The Great Famine (Bhayankar Dushkal): This chapter likely details a severe famine that occurred in ancient India, a period of immense hardship that may have led to exceptions or changes in monastic practices, influencing scriptural interpretations.

-

The First Jain Council (Pratham Bhikshu Sangiti): This section probably discusses the early councils where scriptures were compiled and organized. The author may suggest that events during or after these councils, possibly due to the famine and the need to preserve the tradition, led to some of the ambiguities.

-

A Miracle Created (Sarjela Chamatkar): This chapter title is intriguing and suggests the author will present a narrative or an argument that resolves the apparent contradiction by explaining how the "problematic" passages or interpretations were ingeniously managed, perhaps through a "miracle" of interpretation or reconciliation.

-

The Proportion of Meat-Eating (Mansahar nu Pramanu): This chapter likely quantifies or analyzes the extent to which meat-eating might have been discussed or permitted in specific, perhaps misunderstood, contexts within Jainism.

-

Is it a Stipulated Passage or a Passage of Salvation? (Vidhaan Paath ke Uddhar Paathi): The author questions whether certain passages were meant as general injunctions or as specific exceptions for the salvation/upliftment of practitioners in difficult circumstances.

-

A Fault is Also a Virtue (Dosh e pan ek Sagun chhe): This philosophical point suggests that perhaps even perceived "faults" or exceptions in scriptures had a deeper purpose or led to a greater virtue, such as the preservation of the tradition or the upliftment of practitioners.

-

Achieved Nationwide Great Victory (Prapta Karelo Rashtravyapi Mahavijay): This chapter likely highlights the successful spread and establishment of Jainism across India, attributing this success to the adaptability and profound spiritual strength of the tradition, perhaps even in the face of challenges and misinterpretations.

-

Based on the Teachings of Shri Bhadrabahuswami (Shri Bhadrabahuswami ne Aadhar): This signifies an appeal to the authority of a respected Jain acharya, Bhadrabahuswami, whose interpretations or works are used to support the author's arguments.

-

Imagination Regarding Scriptures (Shastro vishe Bandheli Kalpana): The author addresses how misinterpretations or "imaginations" about the scriptures have led to the current debate.

-

Superstitious Beliefs and Religious Fervor (Vahemi Manyatao ane Dharmaghelchao): This chapter likely discusses how unfounded beliefs and blind adherence to certain interpretations have perpetuated the controversy.

-

Brief Summary of the Essay (Nibandh ne Tuck Saar): A concise recap of the main points.

-

Reasons for the Problem Becoming Complex (Samasya Jatil Banva na Karano): An analysis of why the issue has remained contentious for so long.

-

A Humble Request to Scholars (Pandito ne Namra Vinanti): An appeal to scholars for a thoughtful and critical re-examination of the scriptures.

-

Conclusion (Upsanhaar): The author's final thoughts and reiteration of his stance.

-

Appendix (Parishisht): Supplementary materials, likely containing scriptural references or scholarly discussions.

-

Final Statement (Antim Nivedan): A concluding remark from the author.

Key Arguments and Examples Presented in the Text:

- Linguistic Ambiguity: The author argues that ancient Prakrit and Sanskrit words had broader meanings than their modern interpretations. For instance, the word "maans" (meat) might have referred to fruits, grains, or other edible plant matter in certain contexts.

- Contextual Interpretation: Passages are often misinterpreted because their historical and situational context is ignored. The author highlights that even in the time of Lord Buddha, exceptions for survival during severe famines were discussed, but this does not imply condoning meat-eating.

- The Role of Acharyas: The author analyzes commentaries by prominent Acharyas like Haribhadrasuri and Shilaankacharya. While acknowledging they interpreted some passages in a meat-related context, the author suggests they also noted opposing views and kept the door open for further research, recognizing their own limitations as "chhadmastha" (unenlightened beings).

- The Great Famine (12 years): This period of extreme hardship is presented as a key factor. The text describes the desperate measures people took to survive, including consuming leaves, plants, and even animals. The author argues that any exceptions made by a few monks during such times were for survival and not a departure from core principles. The text also notes the loss of scriptures and the disorganization of the Sangha during this era, which contributed to subsequent misinterpretations.

- The First Jain Council: The council was convened to compile and standardize scriptures after the famine. The author suggests that during this council, to accommodate weakened monks or to reconcile differing views, some new rules or interpretations might have been introduced, leading to the "dual-meaning" passages.

- Bhadrabahuswami's View: The author cites Bhadrabahuswami, a respected acharya, who in his Kalpa Sutra and commentary suggests that while the ninefold delicacies (including meat) should generally be avoided, exceptions were permissible for the sick, weak, or those with strong cravings, but always with strict limitations and under the guidance of elders. This is presented not as permission for meat-eating but as an "Uddhar Path" (path to salvation/upliftment) for those struggling.

- Lord Mahavir's Strictness: The author strongly emphasizes Lord Mahavir's unwavering commitment to Ahimsa, citing his refusal of sesame seeds in a desert due to potential harm to tiny organisms and his strict adherence to principles even when facing death. This is contrasted with Lord Buddha's reported flexibility in certain situations.

- The "Uddhar Path" vs. "Vidhaan Path": The author posits that passages seemingly related to meat are "Uddhar Path" (paths for upliftment/exceptions) rather than "Vidhaan Path" (stipulated rules). These exceptions were meant for specific, dire circumstances and for the gradual upliftment of those with strong lingering desires, not as a license for regular meat consumption.

- Historical Context of Language: The author points out that language evolves, and words change meaning over time. The use of words like "maans" or "matsya" in ancient scriptures might not carry the same restrictive meaning of animal flesh as they do today.

- The Glorious History of Jainism: Despite the textual ambiguities and challenges, the author highlights the immense success of Jainism in spreading its message of Ahimsa, vegetarianism, and ethical conduct across India and even beyond, attributing this to the resilience and dedication of the monks and the inherent strength of the principles. He showcases the influence of Jainism on other religions and rulers like Emperor Ashoka and Kharavela.

- Criticism of Scholars: The author implicitly criticizes scholars like Dharmanand Kosambi for relying on isolated passages without considering the broader context, historical evolution of language, and the fundamental principles of Jainism. He defends the Jain tradition against allegations of meat-eating by highlighting the strict adherence to non-violence and the numerous instances of asceticism and self-sacrifice.

Author's Tone and Approach: The author adopts a scholarly yet passionate tone. He is clearly dedicated to defending Jainism and Lord Mahavir from what he considers unfair accusations. He uses historical analysis, linguistic arguments, and scriptural interpretation to support his claims. While acknowledging the existence of seemingly contradictory passages, he consistently frames them within a context of historical hardship, linguistic evolution, or specific allowances for the weak, all ultimately aimed at preserving the core principles of Ahimsa.

Overall Message: "Jain Dharm Ane Mansahar Parihar" argues that Jainism, as taught by Lord Mahavir, is fundamentally and unequivocally against all forms of meat consumption. The perceived scriptural references to meat are attributed to linguistic nuances, historical exigencies like famine, the need for gradual spiritual upliftment of followers, and misinterpretations by later scholars. The book aims to reassure Jains of their tradition's purity and to equip them with reasoned arguments to counter external criticisms, emphasizing the glorious history of Jain ascetics who spread the message of non-violence despite immense challenges.