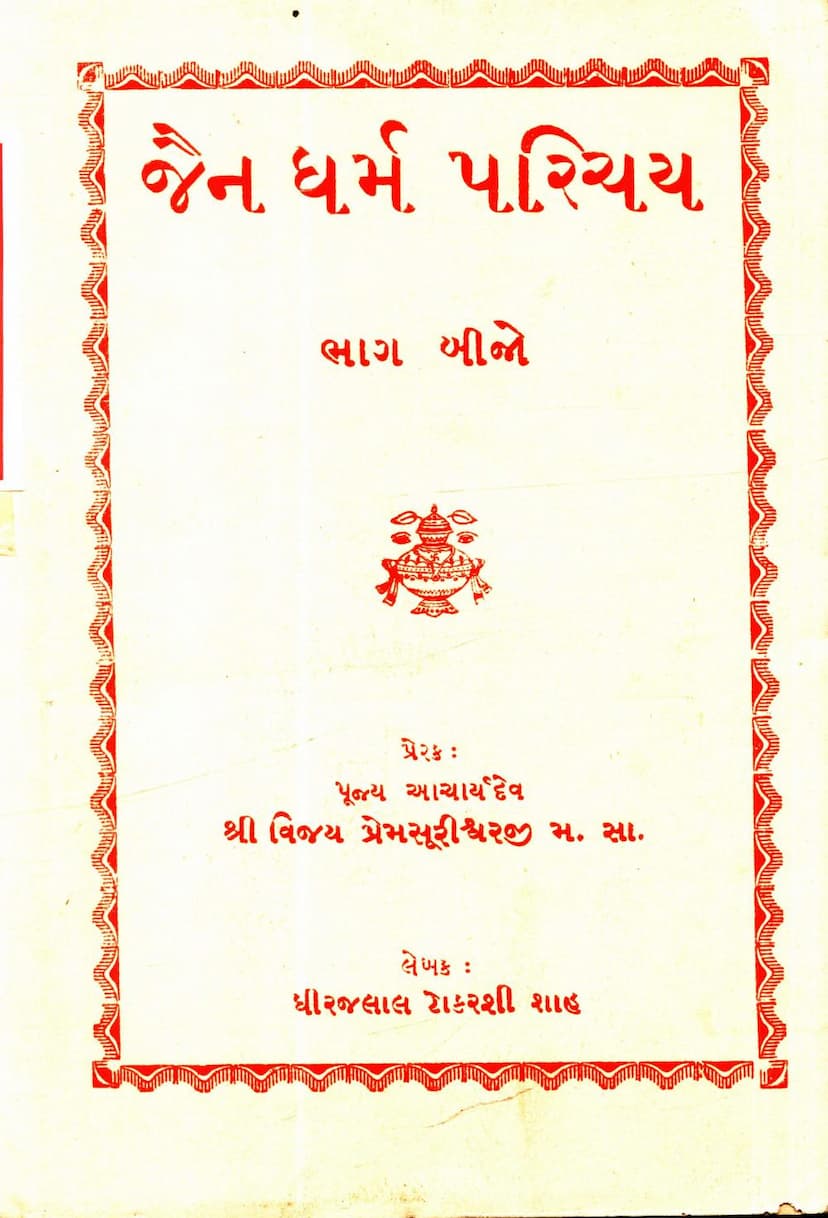

Jain Ddharm Parichay Part 02

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This document is the second part of a book titled "Jain Dharma Parichay" (Introduction to Jainism) by Dhirajlal Tokarshi Shah and published by Vanechandbhai Avichal Mehta. The book aims to provide an accessible introduction to Jain principles for a wider audience, particularly those who may not be familiar with the original Jain scriptures written in older languages.

Here's a summary of the key themes and content covered in the provided pages, organized by chapter as indicated in the table of contents:

Overall Purpose: The book aims to explain the fundamental concepts of Jainism in Gujarati, making them understandable to children and those curious about Jain philosophy. It emphasizes that knowledge of Jainism is essential for spiritual advancement and liberation.

Chapter-wise Summary:

-

Chapter 1: Ātmāno Vikaskram (The Soul's Evolutionary Process)

- This chapter establishes the existence of the soul (Ātmā) by drawing analogies with observable phenomena like wind and electricity, whose existence is inferred from their effects.

- It refutes materialistic viewpoints that deny the soul, arguing that observed phenomena like consciousness and will cannot be explained by mere material combinations.

- The chapter then delves into the nature of the soul, discussing its existence, its subtle (anū) or all-pervading (mahata) nature, and its eternality.

- It asserts that the soul is the doer of its actions and the enjoyer of their fruits.

- The concept of liberation (moksha) is presented as an achievable goal, and the existence of means (upāya) to achieve it is affirmed.

- The core Jain principles are introduced through six foundational statements (Siddhāntas): the existence of the soul, its eternality, its role as the doer and enjoyer of karma, the certainty of liberation, the existence of means to liberation, and the importance of righteous conduct.

- The chapter outlines the fourteen stages of spiritual progress (Guṇasthānas), describing the soul's journey from ignorance (mithyādarśti) through various stages of spiritual development, culminating in omniscience (kevalajñāna) and liberation. It differentiates between souls that can achieve liberation (bhavyātmā) and those that cannot (abhavyātmā).

-

Chapter 2: Yoga Sadhana (Yoga Practice)

- This chapter clarifies that yoga is not exclusive to Vedic traditions but is an integral part of Jainism, with Tirthankaras being referred to as "yogishwar" (masters of yoga).

- It presents the Jain definition of yoga, emphasizing the purification of the soul and connection to liberation through various spiritual practices.

- The core of Jain yoga lies in the five categories of righteous conduct (sthānādi dharma vyāpār): physical posture (sthānāgata), scriptures (vigata), meaning of scriptures (arthāgata), contemplation of the self (ālambana gata), and contemplation without external support (ālambana rahita).

- The chapter explains the purpose of attaining mastery in these practices, highlighting their role in achieving karma-less states essential for liberation.

- It details the types of meditation: Ārtya Dhyāna (sorrowful meditation) and Raudra Dhyāna (fierce/anger-driven meditation) as inauspicious and to be abandoned, and Dharma Dhyāna (righteous meditation) and Shukla Dhyāna (pure/white meditation) as auspicious and conducive to liberation.

- The chapter also touches upon the eight limbs of yoga as described in Vedic traditions (Yama, Niyama, Āsana, Prāṇāyāma, Pratyāhāra, Dhāraṇā, Dhyāna, Samādhi) and explains how Jain practices, while sometimes differing in approach, align with the underlying principles of self-discipline and spiritual focus. It emphasizes the importance of ethical conduct (Yama and Niyama) as a foundation for yoga, highlighting Jain equivalents like the five great vows (Mahāvratas) and the three safeguards (Guptis).

- The discussion on Āsana focuses on the Jain practice of Kāyotsarga (standing in meditation), detailing the proper posture and the importance of maintaining equanimity and detachment from the body.

- The chapter notes that while external Prāṇāyāma (breath control) is considered less essential in Jainism, its internal, mental aspect is embraced.

- The chapter highlights the importance of Adhyātma (self-contemplation) and Bhāvanā (meditation/contemplation) as key practices in Jainism that lead to the desired state of mental clarity and spiritual progress.

-

Chapter 3: Ahimsā (Non-violence)

- This chapter defines Ahimsā as the paramount principle in Jainism, described as "Prāṇātipāta Viramaṇa Vrata" (abstinence from harming life).

- It explains that harm (prāṇātipāta) encompasses the destruction or injury of the ten vitalities of a living being (five senses, mind, speech, body, breath, and lifespan).

- The chapter emphasizes that Jainism recognizes the existence of life in all forms of existence, including plants (Vanaspati Kāya), water (Ap Kāya), fire (Agni Kāya), air (Vāyu Kāya), and earth (Pṛthvī Kāya), in addition to mobile beings (Trasa).

- It distinguishes between different levels of violence, stressing that harming beings with more senses is considered more serious.

- The chapter advocates for minimizing harm in all activities, even those essential for survival. It criticizes ritualistic sacrifices involving animal slaughter and highlights the philosophical inconsistencies in such practices.

- The text strongly condemns hunting and animal cruelty, emphasizing that all beings desire life and happiness.

- It clarifies that violence can be mental, verbal, or physical, and true Ahimsā extends to all three.

- The chapter contrasts the detrimental effects of materialism and violence (leading to war, destruction, and fear) with the peace and well-being promoted by Ahimsā, citing its universal applicability and the profound impact it has on individual and societal harmony.

- It explains how Jain monks and nuns strictly adhere to Ahimsā, employing practices like carrying a broom (Rajoharaṇa) to avoid stepping on insects and a cloth mask (Muhapatti) to prevent harming microscopic organisms in their breath. The chapter provides examples of the extreme dedication of Jain ascetics to Ahimsā, even in the face of extreme suffering or death.

- It also addresses the practical application of Ahimsā for householders, outlining their specific vows and restrictions.

-

Chapter 4: Dāna (Charity)

- This chapter highlights the significance of Dāna as one of the four pillars of Jain dharma, alongside Shīla, Tapa, and Bhāva.

- It emphasizes that Dāna leads to spiritual merit and liberation, while hoarding wealth leads to negative karmic consequences and suffering.

- The chapter distinguishes true Dāna from mere giving, stating that it must be done with genuine compassion and without ulterior motives, criticism, or regret.

- It outlines four types of Dāna:

- Abhayadāna (Gift of Fearlessness): Protecting living beings from harm and fear, essentially synonymous with Ahimsā.

- Jñānadāna (Gift of Knowledge): Sharing spiritual or true knowledge with those seeking it.

- Upashṭambhadāna (Gift of Support): Providing essential material needs like food, water, shelter, and medicine to the deserving, especially ascetics and those in need.

- Anukampādāna (Gift of Compassion): Offering help and support to those in distress or suffering, without discrimination.

- The chapter provides historical examples of Jain philanthropists who have made significant contributions to society through their charitable actions.

- It also outlines the qualities of proper giving, such as giving with joy, offering respect, speaking kindly, and avoiding delay or regret.

-

Chapter 5: Shīla (Virtue/Moral Conduct)

- This chapter emphasizes the crucial role of Shīla (virtuous conduct) in achieving liberation. It states that no one has attained liberation without its practice.

- Shīla is described as the protector of virtue, the destroyer of sin, and the enhancer of character, comparable to ornaments that adorn the body.

- The chapter defines Shīla as adherence to vows and disciplines that lead to self-improvement and spiritual discipline.

- It addresses the misconception that strict vows lead to a dull life, arguing instead that they are a means to freedom from bondage and that adherence, even if challenging, yields greater rewards.

- The chapter discusses the importance of controlling sensual desires, using the examples of the five senses and the suffering caused by uncontrolled indulgence.

- It highlights the concept of Brahmacharya (celibacy or chastity) as a central aspect of Shīla, emphasizing its importance for both ascetics and householders.

- The chapter elaborates on the eighteen branches of conduct (Shīla) for ascetics and the principles of virtuous living for householders, emphasizing the importance of controlling passions and desires.

- The story of Vankachula is used to illustrate how adherence to seemingly simple vows can protect individuals from dire consequences and lead to spiritual growth.

-

Chapter 6: Tapa (Asceticism/Austerities)

- This chapter explains that Tapa is essential for the destruction of karma, which is the path to liberation. Tirthankaras have consistently emphasized and practiced Tapa.

- It defines Tapa as both external (bāhya) and internal (abhyantara) practices of self-discipline and renunciation.

- The chapter clarifies that mere physical endurance (like standing in extreme weather or fasting) without proper understanding and mental discipline is not true Tapa and can even lead to harm (himsa).

- It stresses that Tapa must be performed with knowledge and equanimity, not for worldly gains, fame, or mere physical suffering, but solely for the purpose of karma destruction.

- The chapter lists various types of external Tapa, including fasting (anashana), limited intake (unodari), reduced consumption (vritti samkshep), taste renunciation (rasa tyaga), enduring physical discomfort (kaya klesha), and restrained posture (shaleenata).

- It also details internal Tapa, which includes practices like penance (prāyaśchitta), humility and respect for elders/Gurus (vinaya), service to the needy (vaiyāvṛtya), study of scriptures (svādhyāya), meditation (dhyāna), and detachment (utsarga).

- The chapter emphasizes the importance of balance in Tapa, warning against extremes that could harm the body or mind, and advocating for a gradual approach to spiritual practice.

- It lists a comprehensive catalog of 130 different types of Tapa practiced within Jainism, showcasing the extensive disciplinary practices available.

-

Chapter 7: Bhāva (Inner Disposition/Attitude)

- This chapter emphasizes that genuine religious practice requires a pure inner disposition (Bhāva). It uses the analogy of a doctor without logic, a scholar without character, and a religion without inner feeling being subject to ridicule.

- It explains that Bhāva is the essence of thought, emotion, and intention, and that while actions are important, the underlying attitude is paramount in determining karmic outcomes.

- Jainism categorizes Bhāva into auspicious (shubha) and inauspicious (ashubha). Inauspicious Bhāvas lead to karmic bondage, while auspicious Bhāvas lead to karma destruction and liberation.

- The chapter highlights that auspicious Bhāvas are the driving force behind Dāna, Shīla, and Tapa, making them truly effective.

- It uses the examples of Chakravarti Bharat and Ilaichikumara to illustrate how a profound shift in inner disposition (Bhāva) can lead to immediate spiritual realization and liberation.

- The chapter concludes by advocating for the cultivation of auspicious inner states as the key to spiritual progress and the ultimate attainment of liberation.

-

Chapter 8: Panchāchāra (The Fivefold Conduct)

- This chapter explains the five conduct principles essential for spiritual progress:

- Jñānāchāra (Conduct related to Knowledge): Emphasizes the study and correct understanding of scriptures (Śrutajñāna) and the importance of acquiring knowledge from qualified Gurus with proper respect and devotion. It outlines eight disciplines for this study, including time, reverence, respect, preparation, non-concealment, purity of expression, purity of meaning, and purity of both.

- Darshanāchāra (Conduct related to Right Faith/Perception): Focuses on maintaining pure faith in Jain tenets. It outlines eight principles for this, including freedom from doubt, desire for other paths, aversion to objectionable practices, correct perspective, appreciation of virtues, firmness in faith, affection for fellow practitioners, and propagation of the faith.

- Chāritrāchāra (Conduct related to Right Conduct): This refers to the practice of the five great vows (Mahāvratas) and three safeguards (Guptis) for ascetics, and the twelve vows for householders, all performed with mindfulness and diligence.

- Tapāchāra (Conduct related to Austerities): Reiteration of the importance of Tapa, emphasizing that it should be performed without any attachment to its results or worldly intentions, but solely for karma destruction.

- Vīryāchāra (Conduct related to Energy/Effort): Stresses the importance of consistent and vigorous effort in practicing the other four Āchāras, refuting the notion of fatalism and emphasizing self-exertion.

- This chapter explains the five conduct principles essential for spiritual progress:

-

Chapter 9: Sapta Vyasan Tyāga (Abandonment of the Seven Vices)

- This chapter defines "Vyasan" as vices that lead to suffering and spiritual downfall.

- It identifies and elaborates on seven major vices that are strictly prohibited in Jainism:

- Gambling (Jugār): Described as a highly addictive vice that leads to financial ruin, moral decay, and association with negative influences.

- Theft (Chori): Condemned as a grave offense causing harm to others and leading to severe karmic consequences.

- Meat Consumption (Mānsabhakṣaṇ): Explicitly prohibited due to the inherent violence in obtaining meat, and its adverse effects on spiritual development.

- Intoxication (Madirāpāna): Considered a vice that clouds judgment, leads to loss of self-control, and fosters other sinful activities.

- Adultery/Illicit Relations (Parastrī Sevan): Emphasizes fidelity within marriage and condemns relationships outside of it, highlighting the negative social and spiritual repercussions.

- Prostitution (Veśyāgaman): Strongly condemned as a path to degradation and ruin.

- Hunting (Shikār): Also condemned due to the inherent violence and cruelty involved, advocating for compassion towards all living beings.

- The chapter provides strong arguments against each vice, citing their destructive potential and the negative karmic outcomes.

-

Chapter 10: Jin Bhakti (Devotion to the Jinas)

- This chapter emphasizes the importance of devotion to the Jinas (Jain Tirthankaras) as a means to spiritual progress and the ultimate goal of liberation.

- It defines true Mahapurushas (great souls) as those who have conquered their inner selves, achieved self-control, and attained spiritual purity, like the Tirthankaras.

- Devotion to the Jinas is presented as a vital nimitta (instrumental cause) that supports the soul's own effort (upādāna cause) in its spiritual journey.

- The chapter distinguishes between different types of devotion: Tamasic (driven by negativity), Rajasic (driven by desire for worldly rewards), and Sattvic (driven by the aspiration for spiritual liberation), highlighting Sattvic devotion as the highest and most beneficial.

- It explains that devotion can be expressed through various forms of worship, including bowing (Vandan), ritualistic offerings (Pūjā), showing respect (Satkār), and internal reverence (Sammān).

- The chapter details the practice of offering worship to the images (pratimā) or idols of the Jinas, which are seen as representations of the liberated souls. It describes the different materials used for idols and the various stages of the Jinas' lives (birth, renunciation, omniscience, liberation) that are contemplated during worship.

- It lists prominent Jain pilgrimage sites across India, highlighting their historical and spiritual significance.

-

Chapter 11: Ṣaḍāvaśyaka (The Six Daily Duties)

- This chapter emphasizes the importance of performing daily spiritual practices (Āvaśyaka) for purifying the soul and progressing on the path to liberation.

- It defines "Āvaśyaka" as essential, indispensable duties that must be performed daily.

- The six Āvaśyakas are:

- Sāmāyika: Cultivating equanimity and mental stillness, achieved by renouncing all sinful activities and maintaining a state of mental peace and detachment.

- Chaturviṁśatistava: Offering praise and salutation to the twenty-four Tirthankaras, recognizing their role in guiding souls toward liberation.

- Vandan (Guruvandan): Showing reverence and respect to Gurus and elders, acknowledging their role in spiritual guidance.

- Pratikramaṇa (Repentance): Reviewing one's actions from the previous day/period, repenting for any wrongdoings, and seeking forgiveness to purify the soul.

- Kāyotsarga (Body-abandonment): Standing still in meditation, relinquishing attachment to the body and focusing on the soul.

- Pratyākhyāna (Renunciation): Making vows and resolutions to abstain from certain actions or indulgences, thereby purifying the mind and controlling desires.

- The chapter details the significance and practice of each of these six duties, emphasizing their role in karma-binding prevention (saṁvara) and karma-shedding (nirjarā).

-

Chapter 12: Jñāna (Knowledge)

- This chapter elaborates on the concept of Jñāna (knowledge) within Jainism, explaining its paramount importance for liberation.

- It defines knowledge as the soul's capacity to know and understand, and distinguishes between anatma (non-soul) entities and the soul itself.

- The chapter outlines the five types of knowledge (Jñāna):

- Mati Jñāna: Sensory knowledge acquired through the five senses and the mind.

- Śruta Jñāna: Knowledge gained from scriptures and external sources.

- Avadhi Jñāna: Clairvoyant knowledge of subtle matters within a limited scope.

- Manah-paryāya Jñāna: Telepathic knowledge of others' thoughts.

- Kevala Jñāna: Omniscience, the perfect and complete knowledge of all things in the universe, attained after the complete destruction of karmic obscurations.

- It discusses the conditions and means by which each type of knowledge is acquired, emphasizing the role of karma and the process of its destruction.

-

Chapter 13: Sharīra, Indriyo ane Man (Body, Senses, and Mind)

- This chapter provides a detailed description of the physical body (Sharīra) in Jain philosophy.

- It identifies the five types of bodies that a soul can possess: Audārika (gross physical body), Vaikriyik (transformable body), Āhārak (body for acquiring knowledge from distant places), Taijasa (fiery body for digestion and radiance), and Kārmana (karmic body, the subtlest and most pervasive).

- It explains that the Taijasa and Kārmana bodies are with the soul at all times, even during transmigration, while the other bodies are acquired and shed.

- The chapter then discusses the five senses (Indriyo): touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing, explaining their function in perceiving the material world.

- Finally, it touches upon the mind (Man) as a crucial organ for thought, intention, and spiritual development.

-

Chapter 14: Shāstro ane Sāhitya (Scriptures and Literature)

- This chapter provides an overview of the vast body of Jain scriptures, known as Agamas.

- It explains that the Agamas were originally taught by the Tirthankaras and compiled by learned ascetics (Ganadharas).

- The chapter outlines the structure of Jain scriptures, including the Twelve Angas (main scriptures) and Fourteen Purvas (lost early scriptures), and various other supplementary texts like Upangas, Chedasutras, and Mūlasutras.

- It mentions the languages in which these scriptures were originally written (Ardhamāgadhī) and the subsequent commentaries and explanations in Prakrit and Sanskrit.

- The chapter highlights the immense contribution of Jain scholars and saints in preserving and elaborating upon this rich literary tradition through various commentaries, treatises, and literary works in diverse fields like philosophy, logic, poetry, grammar, and science.

- It emphasizes the profound impact of Jain literature on Indian culture and thought.

This comprehensive summary covers the essential aspects of each chapter, providing a good overview of the "Jain Dharma Parichay Part 02."