Jain Darshannu Tulnatmak Digdarshan

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary in English of the Jain text "Jain Darshannu Tulnatmak Digdarshan" by Hiralal R. Kapadia, based on the provided pages:

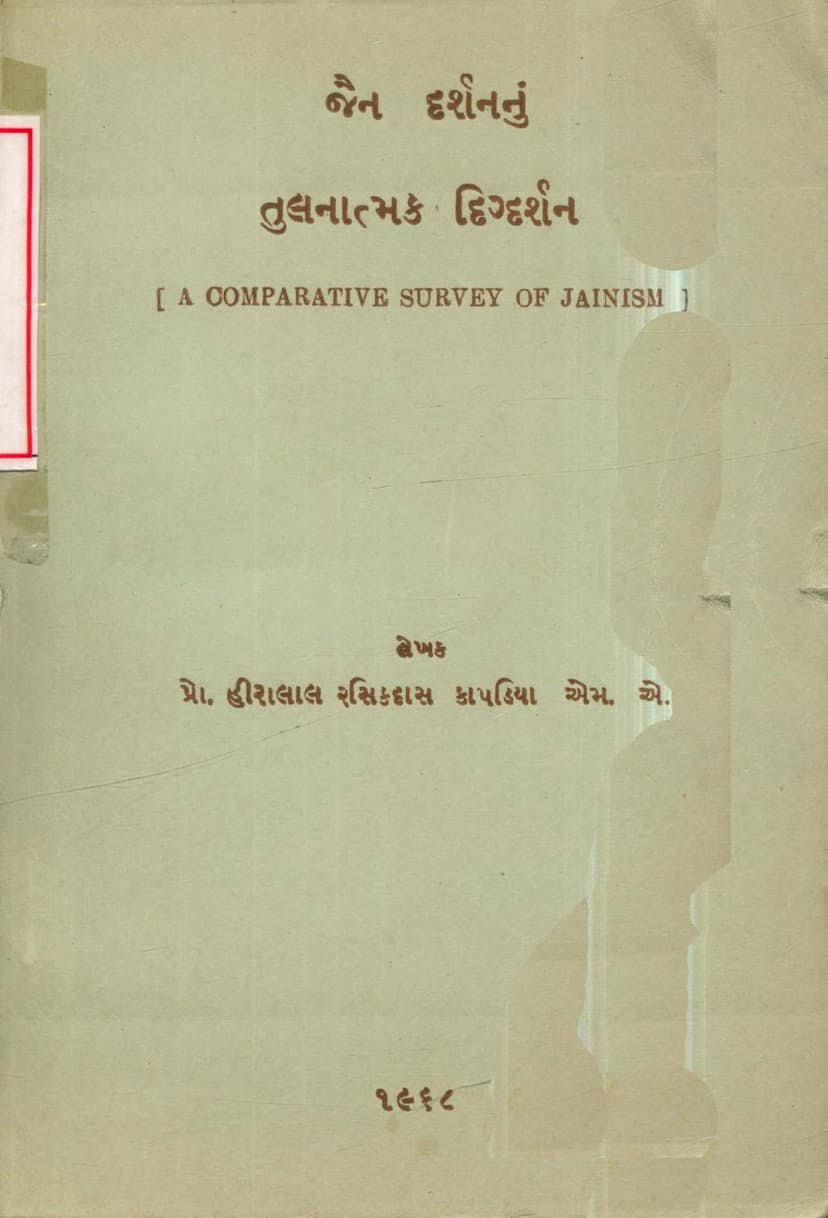

Book Title: Jain Darshannu Tulnatmak Digdarshan (A Comparative Survey of Jainism) Author: Prof. Hiralal R. Kapadia, M.A. Publisher: Shri Nemi Vigyan Kastursuri Gyanmandir Year of Publication: 1968 (Veer Samvat 2484)

Overview:

"Jain Darshannu Tulnatmak Digdarshan" is a foundational work that aims to provide a comparative overview of Jain philosophy. Authored by Prof. Hiralal R. Kapadia, a respected scholar, the book presents Jain tenets in a structured, sutra-based format, drawing heavily from classical Jain scriptures. Its primary objective is to make Jain philosophy accessible to a wider audience, particularly in contemporary times when in-depth study of large texts might be challenging. The book also seeks to highlight Jainism's distinctiveness and its place within the broader spectrum of Indian philosophical traditions.

Key Themes and Content:

The book is structured around 141 sutras, each followed by a commentary that elucidates Jain principles and often draws comparisons with other Indian philosophical schools (Darshanas) such as Sankhya, Vaisheshika, Nyaya, Mimamsa, Vedanta, and Buddhism.

Core Jain Concepts Covered:

-

The Nature of Reality (Sutras 1-3):

- The universe (Jagat) is considered eternal and uncreated, without beginning or end.

- The world is understood as the totality of substances (Padarth).

- Substances are characterized by origination, destruction, and permanence (Utpadavyaya-dhrauvyayuktam Sat).

-

Substances and Their Components (Sutras 4-6):

- Substances (Padarth) are composed of permanent (Guna) and transient (Paryaya) aspects. Dravya is the substance that undergoes change, and Paryaya is its modification.

- Substances are categorized into sentient (Jiva/Chetana) and non-sentient (Ajiva/Jada).

- Jivas are inherently conscious (Bodha), a quality that is self-illuminating and illuminating of others.

-

The Jiva (Soul) (Sutras 7-10):

- The Jiva is defined by consciousness (Bodha).

- Jivas are classified as embodied (Samsari) and liberated (Mukta).

- Embodied Jivas are further divided into those with passions (Saraga) and those without passions (Vitaraga).

- The soul's consciousness is described as self-revealing and other-revealing.

-

Knowledge (Jnana) (Sutras 11-15):

- Jainism recognizes five types of knowledge: Mati (sensory/inferential), Shruta (scriptural), Avadhi (clairvoyance), Manahparyaya (telepathy), and Kevala (omniscience).

- Mati and Shruta are considered indirect (Paroksha), while Avadhi, Manahparyaya, and Kevala are direct (Pratyaksha).

- Kevala Jnana, omniscience, is considered perfect and attained by the Vitaraga beings.

- Shruta is divided into the Twelve Angas (Dvadashangi) and other scriptural texts.

-

Categories of Beings and Life Forms (Sutras 18-26):

- Beings are classified based on the number of senses they possess, from one-sensed (Ekendriya) to five-sensed (Panch-endriya).

- One-sensed beings include earth-bodied, water-bodied, fire-bodied, air-bodied, and plant-bodied souls.

- Plant-bodied souls are further divided into individual (Pratyeka) and communal (Sadharana).

- The concept of Nigoda (subterranean beings) is introduced, with beings existing in subtle and gross forms.

- Five-sensed beings are categorized into humans, celestial beings (Deva), hellish beings (Naraka), and some animals (Tiryancha).

-

The Mind (Manas) (Sutras 27-31):

- The mind is considered an internal sensory organ, present throughout the body, and capable of perceiving both gross and subtle matters.

- The mind is divided into material (Dravya-mana) and substantial (Bhava-mana) aspects.

- Only beings with "Sampradharana-sanna" (discriminating consciousness) possess a fully developed mind.

- Births are classified as oviparous (Garbha) and spontaneous (Sammurchhim) for humans and animals, and divine (Aupapatika) for celestial and hellish beings.

-

Non-Sentient Substances (Ajiva) (Sutras 32-41):

- The non-sentient substances are Akash (Space), Pudgala (Matter), Dharma (Medium of Motion), and Adharma (Medium of Rest). Digambaras also include Kala (Time), while Shvetambaras consider it a formal substance.

- Pudgala possesses touch, taste, smell, and color, and is the only substance with these attributes.

- Sound, darkness, shadow, heat, and light are considered Paugdgalika (material).

- Matter is ultimately composed of indivisible atoms (Paramanu), each having one color, taste, smell, and two types of touch.

- Dharma and Adharma are ubiquitous, eternal, and assist in motion and rest respectively.

- All substances, except for the entirety of space, possess multiple spatial units (Pradesha).

-

Karma Theory (Sutras 42-70):

- The Jiva's size contracts and expands like a flame.

- Karmic matter (Karma-vargana) adheres to the soul, influencing its state.

- Actions (Yoga) in body, speech, and mind lead to the influx of karma (Asrava).

- Karma binding is driven by passions (Kashaya) and actions (Yoga).

- Four aspects of karma are formed: Nature (Prakriti), Duration (Sthiti), Intensity (Rasa), and Quantity (Pradesha).

- Karmas are broadly classified as Obscuring (Ghati) and Non-Obscuring (Aghati).

- Obscuring karmas (Mohaniya, Jnanavaran, Darshanavaran, Antaray) hinder the soul's inherent qualities.

- Mohaniya (delusion) karma is the greatest enemy, further divided into Darshan-Mohaniya (affecting right faith) and Charitra-Mohaniya (affecting conduct).

- The nine Nókashayas (secondary passions) like laughter, pride, etc., are also discussed.

- The five types of Jnanavaran (knowledge-obscuring) and nine types of Darshanavaran (perception-obscuring) are detailed.

- The five types of Antaray (obstacles) are explained.

- Non-obscuring karmas (Vedaniya, Nama, Gotra, Ayushya) affect the physical and circumstantial aspects of the soul.

- Vedaniya karma causes pleasure (Sata) and pain (Asata).

- Nama karma determines the soul's rebirth circumstances.

- Gotra karma determines social standing.

- Ayushya karma determines lifespan.

- The distinction between meritorious (Punya) and demeritorious (Papa) karmas is made, with specific karmic activities classified under each.

- Karma operates impersonally; no external deity is needed to administer its fruits.

- The nature of karma binding and the possibility of transmigration of karmic seeds (Sankramana) are explained.

-

The Path to Liberation (Moksha Marga) (Sutras 71-141):

- Bodies: Five types of bodies are described: Audarika (gross), Vaikriya (transformable), Aharaka (transmigratory), Taijasa (luminal), and Karmana (karmic).

- Perfections (Paryapti): Souls achieve perfections in nourishment, body, senses, breath-activity, speech, and mind.

- Vitalities (Prana): Ten vitalities are listed, including senses, strength, breath, and lifespan.

- The Three Jewels (Trividha Marga): Right Faith (Samyakdarshana), Right Knowledge (SamyakJnana), and Right Conduct (SamyakCharitra) are the path to liberation.

- Seven Realities (Tattva): Jiva, Ajiva, Asrava, Bandha, Samvara, Nirjara, and Moksha.

- Means of Knowledge (Pramana): Perception (Pratyaksha) and Inference (Paroksha).

- Standpoints (Naya): Different perspectives for understanding reality, including Dravyarhtika (substance-oriented) and Paryayarhtika (state-oriented) nayas, with their sub-categories (Naigama, Sangraha, Vyavahara, Rjushutra, Sampratyay, Sambhi-rudha, Evambhuta).

- Syadvada (Anekantavada): The doctrine of conditional predication, emphasizing that reality is multifaceted and can be viewed from various perspectives. It is presented as a tool for reconciling differing philosophical views and upholding non-violence (Ahimsa).

- Causes of Action (Nimitta): Time, nature, destiny, past karma, and self-effort (Purushakara).

- Modes of Classification (Nikshepa): Nama (name), Sthapana (representation), Dravya (substance), and Bhava (state).

- Jainism's Identity: The term "Jain" derives from "Jina" (victor), signifying one who has conquered passions. The book discusses the "Jinas" (Tirthankaras) and the six philosophical systems (Shad Darshana) as their "limbs."

- Ahimsa (Non-Violence): Emphasized as the paramount vow. Violence is defined as destruction of life due to negligent activity (Pramatta Pravritti).

- Mahavratas and Anuvratas: The five great vows for ascetics and the five minor vows for householders.

- Austerities (Tapa): External and internal austerities are crucial for purification.

- Samvara and Nirjara: Samvara is the stoppage of karmic influx, and Nirjara is the shedding of accumulated karma.

- Liberation (Moksha): The ultimate state of soul liberation from all karmas. It is attained through the destruction of Obscuring karmas, leading to omniscience, infinite perception, bliss, and power.

- Tirthankaras: Highly virtuous beings who establish the Jain order; they are not considered avatars but liberated souls who manifest the Dharma.

- Human Birth: Emphasized as a rare and precious opportunity for spiritual advancement and liberation.

- Free Will vs. Destiny: Jainism rejects fatalism, emphasizing the role of self-effort (Purushakara) alongside other causes.

Key Aspects Highlighted by the Author and Commentators:

- Accessibility: The book aims to simplify complex Jain doctrines, making them understandable for the common reader who may not have access to voluminous texts.

- Comparative Approach: The comparative analysis with other Indian philosophies is a significant feature, highlighting Jainism's unique contributions and perspectives.

- Scholarly Rigor: The author's extensive research and reliance on original Jain scriptures are evident. The foreword by Muni Jambuvijayji notes the use of Tattvartha Sutra and the critique of certain interpretations, suggesting a dedication to accuracy.

- Jainism as a Way of Life: The introduction emphasizes that Jainism is not just a doctrine but a philosophy for living, offering guidance for a successful life.

- Non-Sectarianism: The text implicitly promotes a spirit of respect for other traditions while clearly articulating Jain principles.

Significance:

"Jain Darshannu Tulnatmak Digdarshan" serves as an invaluable resource for anyone seeking a structured and comprehensive understanding of Jain philosophy. It bridges the gap between ancient Jain texts and the modern reader, offering a clear, systematic, and comparative exposition of its core tenets. The book's approach makes it a valuable tool for students, scholars, and practitioners interested in comparative Indian philosophy and Jainism in particular.