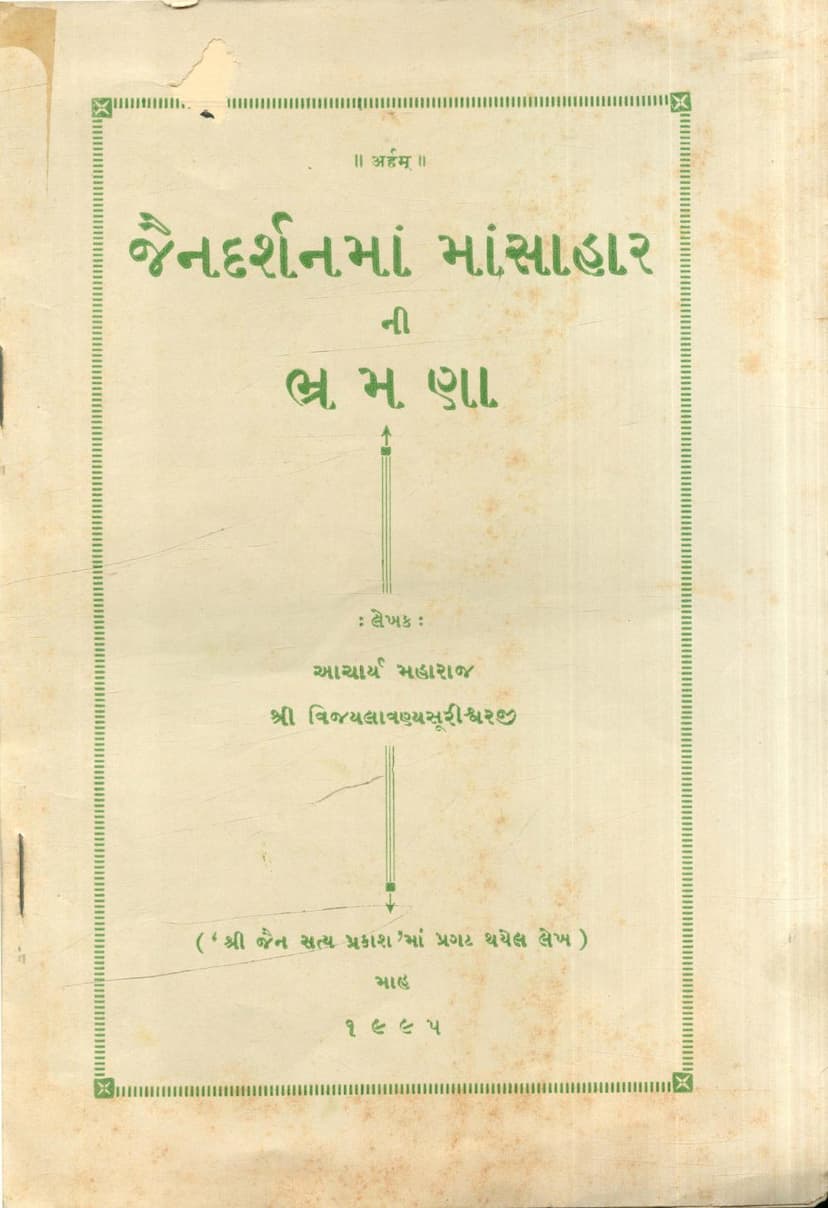

Jain Darshanma Mansaharni Bhramna

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This Jain text, "Jain Darshanma Mansaharni Bhramna" (The Illusion of Non-Vegetarianism in Jain Philosophy) by Acharya Vijaylavanyasuri, published by Jain Satya Prakash, is a detailed rebuttal to an article by Gopaladas Jivabhai Patel. The author, Acharya Vijaylavanyasuri, addresses the claims made by Patel, which are presented as distorting Jainism and suggesting the acceptance of non-vegetarianism within Jain principles.

The core of the text is a point-by-point refutation of Patel's arguments, which are summarized by the author as follows:

- Jainism did not play a significant role in promoting vegetarianism during its early stages.

- Jainism played a significant role in promoting vegetarianism much later, after the time of the commentators who maintained the meaning of "meat."

- Before the promotion of vegetarianism, non-vegetarianism was prevalent and unrestricted in Jainism.

- Lord Mahavir consumed non-vegetarian food.

- Ancient commentators interpreted the word "meat" as meat and "fish" as fish.

- Even if some ancient commentators interpreted the word as referring to plants, the author (Patel) has retained the meaning of "meat" wherever it can be found in any ancient commentator's interpretation.

Acharya Vijaylavanyasuri systematically refutes each of these points, drawing upon Jain scriptures and logic:

- Refuting Point 1 & 2 (Jainism's early role and timing): The author emphasizes that Jainism is a philosophy dedicated to detachment and liberation (Moksha). It cannot promote any particular type of diet. However, for those who must eat, Jainism advocates for a purely vegetarian diet to minimize harm. This principle was not absent during the time of Lord Mahavir; rather, it was strongly propagated. The author highlights that Lord Mahavir, along with his disciples and followers, disseminated these teachings extensively, as evident in the Jain scriptures.

- Refuting Point 3 (Prevalence of non-vegetarianism): The author strongly refutes the claim that non-vegetarianism was prevalent and unrestricted in Jainism. He asserts that this is due to gross ignorance, as Jain scriptures repeatedly condemn non-vegetarianism as a cause of great suffering and a path to hell.

- Refuting Point 4 (Lord Mahavir's non-vegetarianism): The author emphatically denies that Lord Mahavir consumed non-vegetarian food, citing his profound compassion, austerity, and fearlessness. He states that Patel's claims are based on misinterpretations.

- Refuting Point 5 & 6 (Interpretation of "meat"): The author clarifies that the original texts do not contain the words "meat" or "fish." Instead, they use words like "mansa" or "maccha." He criticizes Patel for taking liberties with these words and forcing a meat interpretation. He cites the commentary of Acharya Haribhadrasuri, a highly respected ancient commentator, who interprets these words as specific types of fruits. The author argues that Patel's reliance on isolated interpretations from some commentators while ignoring others (like Haribhadrasuri) is driven by a desire to prove his point about non-vegetarianism. He also questions Patel's methodology in selecting his preferred interpretations.

The text then moves to a lengthy critique of Patel's attempt to equate Lord Mahavir with Goshala, a leader of the Ajivika sect, and to suggest that Mahavir consumed meat based on interpretations of the Bhagavati Sutra.

-

Critique of Goshala's equivalence to Mahavir: The author meticulously deconstructs Patel's claims about Goshala and the Ajivikas. He argues that Goshala was not a Tirthankar (a spiritual conqueror and founder of a spiritual lineage) in Jainism, nor was the Ajivika sect as significant as Jainism, Buddhism, or Brahmanism, as evidenced by its eventual disappearance. He also challenges the interpretation of certain passages in the Bhagavati Sutra, explaining that terms like "tejo-leshya" (a type of spiritual power) and other descriptions are being misinterpreted by Patel.

-

Detailed analysis of the Bhagavati Sutra passages: A significant portion of the text is dedicated to dissecting specific verses from the Bhagavati Sutra (15th Shatak) that Patel uses to support his claims. The author painstakingly analyzes the original Prakrit and Sanskrit words, exploring their various meanings (etymological, medical, contextual, and common usage). He argues that words like "kashaya," "sharira," "marjala," "kritaka," "kukkuta," and "mamsaka" do not inherently mean meat or fish. Instead, they can refer to specific plants, fruits, or even colors and qualities when understood in their proper context.

- He provides detailed explanations of each problematic word, referencing ancient lexicons, medical texts (like Sushruta Samhita), and other Jain scriptures.

- He argues that the context of the Bhagavati Sutra passage, which describes Lord Mahavir's illness and the preparation of food, points towards vegetarian items like plantains and citron fruit preparations, not meat. He uses the example of the word "mamsaka" which, in medical contexts, refers to the pulp of fruits like citron, not animal flesh.

- He refutes the idea that Lord Mahavir would have consumed or sanctioned the consumption of meat, emphasizing Jainism's absolute prohibition of violence and non-vegetarianism. He highlights the purity of food accepted by Jain monks and the concept of "dana" (charity) being associated with pure, vegetarian offerings.

- The author also addresses the concept of "alaukik" (supernatural) in relation to the illness and cure, arguing that the explanation provided in the Bhagavati Sutra for Mahavir's recovery involves a medicinal preparation, which is ultimately a worldly and natural remedy.

-

Reference to Professor Jacobi's views: The author includes a translated excerpt from Professor Hermann Jacobi, a Western scholar who initially interpreted certain passages in the Acharanga Sutra as potentially allowing for non-vegetarianism but later revised his views. Jacobi's revised understanding supports the interpretation of these passages as referring to plant-based foods or metaphorical concepts rather than actual meat. The author uses Jacobi's revised stance to further strengthen his argument against Patel's claims.

-

Rejection of false equivalencies in violence: The author strongly rejects Patel's argument that eating plants is as violent as eating meat. He explains the fundamental difference between the violence involved in harming plant life and the severe violence of killing sentient, five-sensed beings for food, emphasizing the Jain principle of minimizing harm.

In conclusion, "Jain Darshanma Mansaharni Bhramna" is a robust defense of Jain vegetarianism. Acharya Vijaylavanyasuri meticulously dissects and refutes the arguments presented by Gopaladas Jivabhai Patel, using scriptural evidence, linguistic analysis, and logical reasoning to demonstrate that Jain philosophy strictly prohibits non-vegetarianism and that the interpretations suggesting otherwise are erroneous and based on misreadings of sacred texts. The text highlights the profound commitment of Jainism to non-violence (ahimsa) and the purity of diet.