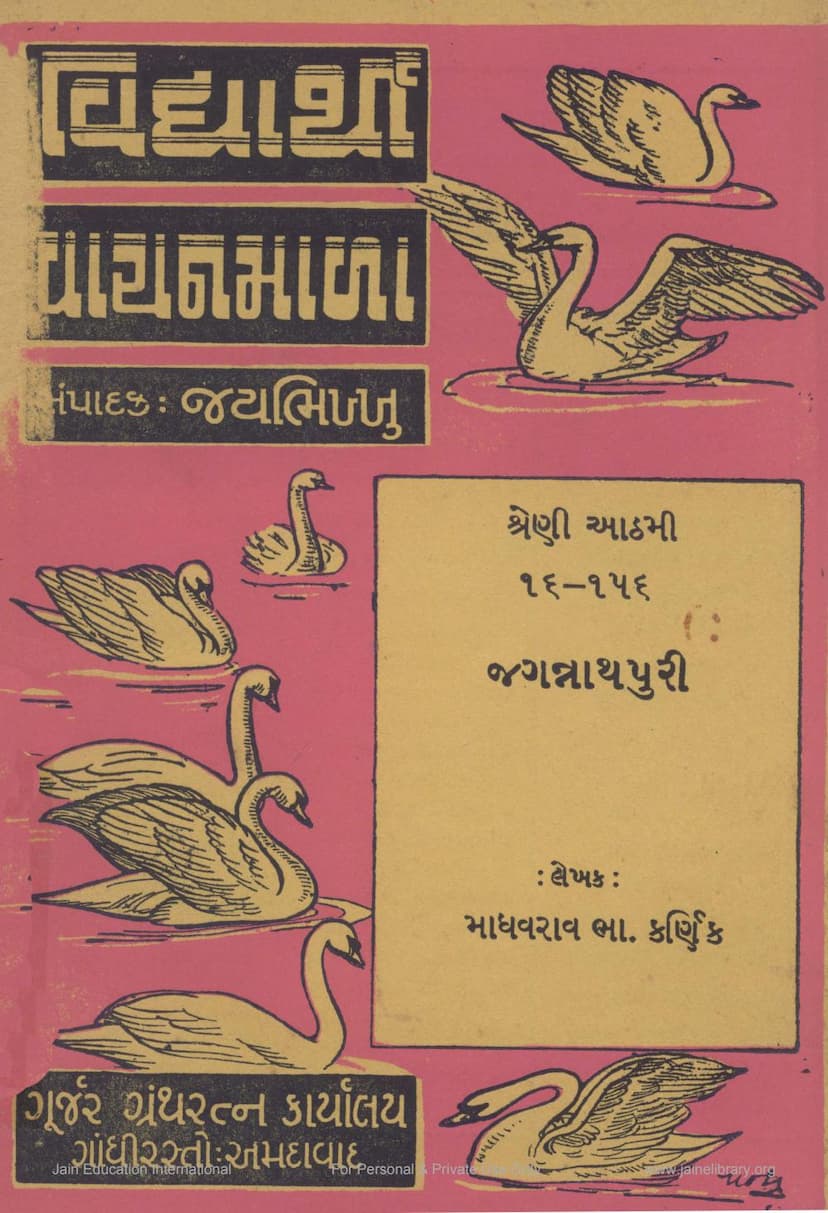

Jagannathpuri

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Jagannathpuri" by Madhavrav B. Karnik, edited by Jaybhikkhu, based on the provided pages:

Overview of the Book and Series:

The book "Jagannathpuri" is part of the "Vidyarthi Vachanmala" (Student Reading Series), specifically within the eighth series (catalog number 16-156). The publisher is Vidyarthi Vachanmala, and it is distributed by Gurjar Grantharatna Karyalaya in Ahmedabad. The series aims to provide educational and inspirational content for children, adolescents, and young adults, covering a wide range of topics including history, biography, mythology, and moral stories. This particular volume focuses on the historical and cultural significance of the Jagannathpuri temple and its associated town.

Jagannathpuri: A Sacred Pilgrimage Site and Its History:

The book introduces Jagannathpuri as one of the four dhams (sacred pilgrimage sites) in Hinduism, strategically located on the eastern coast of India, in the direction of the rising sun. It is also identified as one of the seven holy cities of India.

The historical account of Jagannathpuri begins with evidence suggesting its origins in the Rigvedic period, when a group of Vishnu devotees arrived in the region (Utkal). They established the first sacred site and a sacrificial altar. Later, around 5,000 years ago (3,000 years BCE), the Pandavas also visited this sacred altar.

Initially, the area was ruled by the Shavara tribe, whom the Aryans considered untouchable. However, the Shavaras were described as civilized and had a strong kingdom. Over time, religious conflicts arose in India, leading to a decline in Hinduism and a rise in Buddhism, which was considered a branch of Hinduism. During this period, the importance of Jagannathpuri diminished.

Following the decline of Buddhism and its internal schisms, the importance of the Jagannath temple decreased further, with the Shavara priests maintaining it in a rudimentary state. Subsequently, Brahmin priests from Puri revived Vedic Hinduism in the region. They did not ostracize the Shavaras but rather reformed them, bestowing upon them the sacred thread and initiating them into Brahmanical rituals, thereby restoring the temple to its former glory.

The prestige of Jagannathpuri spread throughout India, attracting thousands of pilgrims. The text mentions King Harshavardhana conquering the Utkal region during this time. In approximately 245 CE, a Chinese general named Raktavahu invaded Utkal. During this invasion, a neighboring king named Shivgupta of the area took the idols of Jagannathpuri and hid them in the forests of Shonpur.

After Raktavahu's invasion, the Jagannath temple lost its grandeur, and devotees experienced great disappointment. It was around the 9th century that the kings of the Simha (Kesari) dynasty of Puri restored the Jagannath idols. They rebuilt the temple with significant expense and brought the idols back from Shonpur, reinstating them with the help of Brahmin priests.

Following the Kesari dynasty, the Ganga dynasty conquered Utkal and significantly enhanced the importance of Jagannath. They dedicated all their kingdom's revenue to the temple, considered themselves the gatekeepers of Jagannath, and would sweep the path ahead of the deity's procession with brooms. King Bhima of this dynasty rebuilt the Jagannath temple in 1196 CE at a cost of 4 million rupees, a structure that still stands today.

After the Ganga dynasty, the Surya dynasty ruled Utkal. They donated numerous villages to the temple and presented a large Sudarsana Chakra (discus), which is still present in the temple. Around 153 CE, the renowned saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu visited Jagannathpuri and spent his entire life there, greatly enhancing the temple's fame.

Challenges and Persecutions:

Despite facing various adversities, the temple's significance remained largely unaffected until the time of Maharaja Pratapadra. From 1503 CE onwards, Muslim invasions of Orissa began with the objective of destroying the Jagannath temple and its idols. The Muslim general Kala Pahar, a former Bengali Brahmin, wreaked havoc.

Kala Pahar conquered Orissa and marched towards Puri. Upon hearing this, a massive gathering of about a million people assembled at the temple to protect their beloved deity. A fierce battle ensued, but due to being outnumbered, the Hindus were defeated. Kala Pahar entered the temple with his sword, intending to destroy the idols.

As Kala Pahar entered, the priests fled with the idols towards Chilka Lake. Kala Pahar pursued them. With no other means of escape, the devotees placed the idols in a pot, set it ablaze, and then threw it into the Mahanadi River when the Muslims tried to seize it. A devotee rescued the burning idols and hid them in a craftsman's house in Kunjag village.

Twenty years later, during the reign of King Ramachandra Dev of Orissa, the idols were restored and re-consecrated. At this time, Emperor Akbar showed great devotion and provided protection to the site. Akbar's generals, Raja Jaysingh and Raja Mansingh, donated hundreds of rupees to the temple, enhancing its glory in 1592 CE.

Later, Raja Dyrsinh ascended the throne. During his reign, Emperor Aurangzeb, driven by religious fanaticism, sent a large army under the command of Pir Muhammad to demolish the temple. King Dyrsinh, lacking the strength to resist Aurangzeb, cunningly saved the idols. He built a new shrine and placed a large, jeweled idol of Jagannath there. Dyrsinh personally met Pir Muhammad and informed him that he had no objection to the idols being broken. They went to the temple, where Pir Muhammad was led to the assembly hall. He broke the large idol and sent the broken pieces along with two diamonds from the idol's eyes to Aurangzeb. Before Aurangzeb could uncover this deception, he died, and shortly thereafter, the Marathas invaded.

The Maratha warriors brought peace and order to Orissa, donated one million rupees to the temple, and restored its reverence with immense faith and devotion. They replaced the collapsed Garuda pillar at the temple's entrance with a stone pillar that remains to this day.

In 1804 CE, the British took control of Orissa from the Marathas and began administering the temple. However, Christian authorities, being anti-idolatry, found it difficult to manage a Hindu temple. Due to their opposition, the British government relinquished administrative control and handed it over to the local Raja of Jagannathpuri. This administration continued until the merger of princely states. The text uses this history as an example of the consequences when people engage in internal strife and lose their country.

Architecture of the Jagannath Temple:

The present-day Jagannath temple is situated on a beautiful sea coast. The area was originally known as Nilachal. The current temple is divided into four parts. The temple courtyard measures approximately 665 feet east-west and 664 feet north-south. It is surrounded by a strong, 24-foot high wall made of black stone, built during the reign of Raja Purushottam Dev. The wall has four gates: Simhadwar, Khadadwar, Hastidwar, and Arudwar. Simhadwar is made of black stone with magnificent lion sculptures on either side, showcasing excellent craftsmanship. The entrance features statues of the gatekeepers Jaya and Vijaya. Opposite the gate stands the 44-foot high Arun Stambh. Khadadwar has no sculptures. Hastidwar features two elephants, and Arudwar has two pot designs.

Entering through the eastern gate, one gets a magnificent and vast view of the temple, which is described as dazzling. To the left are the idols of Shri Kashi Vishwanath and Shri Ramachandra. After climbing twenty-two steps and descending, one enters the inner courtyard, which is approximately 400 feet east-west and 278 feet north-south. In the center of this courtyard stands the grand and imposing temple of Jagannath, surrounded by numerous other temples dedicated to various deities.

The temple of Lord Jagannath has four sections:

- Jagannathji's Temple (westernmost)

- Mohan Mandir (in front of it)

- Natya Mandir (in front of Mohan Mandir)

- Bhoga Mandap (in front of Natya Mandir)

The Bhoga Mandap is about 58 feet east-west and 56 feet north-south. Above its entrance are beautiful sculptures of the nine planets. It has four entrances, but since it's where offerings are placed, all doors except the western one remain closed.

Behind the Bhoga Mandap is the Natya Mandir, which is 80 feet long and wide, with four doors. The eastern door features the idols of Jaya and Vijaya. Behind the Natya Mandir is the Mohan Mandir, which is 50 feet above ground level. Its walls are 120 feet high, and its appearance is like a tent or pyramid. Behind it is the main temple of Jagannathji. The original sanctuary, which exists today, was built by Maharaja Chodaganga, a king of the Ganga dynasty. This temple covers 80 feet of ground and has an artistic dome that is 192 feet high, visible from a great distance.

Pilgrims enter the temple through the Simhadwar. After having darshan there, they proceed to the Natya Mandir, then to the Mohan Mandir, and finally worship the Gada Murtis. From there, they reach the Mahadi. The Mahadi is 16 feet long and 4 feet high. To the south of the Mahadi are the idols of Balarama, followed by Subhadra, then Jagannathji (Lord Shri Krishna), and finally Sudarshana. In front of these idols are gold idols of Lakshmiji, a silver idol of Vishvadhatri, and a brass idol of Shri Krishna.

Darshan of the idols must be performed from a specific spot between the chamber with the idols and the Mohan Mandir. The temple is dark, with only two oil lamps burning, allowing for only indistinct glimpses of Jagannathji.

Daily Rituals and Festivals:

The temple has daily rituals, including morning arati (worship with lamps), adorning the deities, and different types of shringars (decorations) throughout the day:

- Aram Shringar (rest decoration) after arati.

- Dwiprahar Shringar (afternoon decoration).

- Chandan Shringar (sandalwood decoration) around 4 PM.

- Shayan Shringar (nighttime decoration).

Each time, the idols are dressed in new clothes, presented to the public in that form. Sometimes, during the dressing, the idols are given the forms of Damodar, Vamana, etc.

The day begins with the blowing of trumpets by drummers, accompanied by the Mangal Arati. This is followed by rituals like washing the face, bathing, offering balbhog (morning food), and pratahbhog (early morning food), which includes items like yogurt, puffed rice, and fruits. In the afternoon, lunch offerings are made. Around 4 PM, the deities are awakened with jalebi offerings. This is followed by Sandhya Naivedya (evening offerings) of various sweets and then Mahashringar Bhog, which includes the sweet dish Gopalvallabh, sent by the Raja of Puri. Each offering is preceded by worship and followed by arati.

The rice offered to the deity is called Mahaprasad. This prasad is prepared by an untouchable Shavar, and it is consumed by every Hindu, from Brahmins to Bhangis, regardless of caste. At the holy Jagannathpuri, all Hindus are considered equal. This is the daily routine of the Jagannathji temple, in addition to other festivals.

The main festivals celebrated are:

- Chandan Yatra (22 days from Akshaya Tritiya in Vaishakh month), where idols are taken for a boat ride in the nearby Narendra Sarovar.

- Pratishtha Mahotsav (on Vaishakh Sud Ekadashi), commemorating the first consecration of the idols by Maharaja Indradyumna.

- Rukmini Haran and Marriage Ceremony (on Jeth Maas Sud Ekadashi) at the nearby Gudicha temple.

- Snana Yatra (on Jeth Maas Purnima), where idols are taken to the lake for a ritualistic bath. For fifteen days afterward, the idols are kept in seclusion, believed to be suffering from the exertion of the bath. During this period, worship, offerings, and darshan are suspended.

- Ratha Yatra (on Ashadh Sud Bije), the most significant festival. Three new chariots are built annually for this. Jagannathji's chariot is 48 feet high, 35 feet long and wide, with 16 iron wheels of 7-foot diameter. The chariot is called Garuda Dhwaj Ratha. Balarama's chariot is 44 feet high and 34 feet long and wide, marked with a palm symbol, called Tala Dhwaj Ratha. Subhadra's chariot is 43 feet high and 32 feet long and wide, with 12 wheels of 6-foot diameter, and a lotus symbol at its apex, called Kamala Dhwaj Ratha. On Ratha Yatra day, the idols' hands and feet are joined with gold and silver limbs. The Raja of Puri, dressed in royal attire, sweeps the path in front of the chariots with a jeweled broom, performs worship, and pulls the silken rope of the chariot alone. After the Maharaja initiates the process, 4,200 laborers and pilgrims assist in pulling the chariots. This festival lasts for eight days.

- Trimurti Swayan (on Ashadh Ekadashi), where the idols are placed on a palanquin in a sleeping posture, known as Shayano Festival.

- Hindola Festival (from Shravan Maas Sud Ekadashi to Purnima), where idols are placed on a swing in a decorated hall with singing and dancing.

- Janmotsav (on Shravan Vad Athme), celebrating the birth of the deity. A dancer takes on the role of Devaki, and a priest takes on the role of Vasudeva.

- Kaliyadaman Festival (on Shravan Vad Ekadashi) at the nearby Markandeya Sarovar.

In total, twenty-one festivals are celebrated.

Surrounding Attractions and the City:

The book mentions numerous other temples and sacred lakes in and around the Jagannathpuri temple and the city, including Markandeya Sarovar, Indradhumna Sarovar, Chakrateerth Sarovar, and temples like Dharmeshwar, Shvetaganga, Kapalmachan, and Loknath.

The city of Jagannathpuri itself is not particularly notable, although it has seen recent improvements with new constructions. Along the seashore, there are government buildings like the Collectorate, and British officials visit during the summer for a change of air. The language spoken here is Oriya. The province is called Orissa or Utkal. According to the Indian Government Act of 1935, Orissa became a separate province.

Climate and Visitor Amenities:

The climate of Jagannathpuri is described as not very good. However, lakhs of people visit annually for pilgrimage. The fame of Jagannath is widespread throughout India. For pilgrims, there are ample facilities like charitable dispensaries and dharamshalas (rest houses). The text highlights that millions of Hindus, divided by the caste system in India, come here and forget their caste distinctions. They eat the Mahaprasad of Jagannathji, embracing the ideal that all Hindus are one, with no one being untouchable or higher or lower. However, it is lamented that upon returning home, they forget the message of equality from this holy land of Shri Krishna.

Origin of Jagannath Idols:

The stories related to the idols of Jagannathji are found in various Hindu scriptures such as the Brahmavaivarta Purana, Narada Purana, Skanda Purana, Padma Purana, and others. The essence of these stories is as follows:

In ancient times, there was a king named Maharaja Indradyumna. One day, he was sleeping on his jeweled bed, with his queen fanning him. Suddenly, a beautiful Vimana (celestial chariot) descended, and from it emerged a divine, radiant, and majestic male figure. This was Lord Vishnu, who had come to grant the king a boon due to his devotion.

The king asked for a boon to benefit the world and uplift the Aryans. Lord Vishnu told him that the next day, he would see a divine tree on the sandy plains by the sea in Nilachal. From the wood of this tree, the king should create his idol. Vishnu assured him that he would reside in the idol, making the place eternal. With these words, Lord Vishnu departed to heaven.

The next morning, before sunrise, Maharaja and Maharani went to the seashore. In the vast sandy expanse, they found a beautiful, flourishing divine tree (Devdar). The Maharaja began cutting the tree with an axe and took its central portion. He placed the trunk in the sacrificial hall and ordered the state sculptors to carve idols from the wood.

The sculptors began their work, but their tools became blunt, and many tools were rendered useless as they could not make a single mark on the sacred wood. When the Maharaja learned of this, he gathered hundreds of sculptors from across the country, but none could work with the wood.

One day, a worried Maharaja sat contemplating how the idols would be made. Suddenly, an old, trembling sculptor approached him, requesting to be entrusted with the task of carving the idols. The Maharaja, shocked by the appearance of the ancient sculptor, but as a last resort, agreed.

The sculptor stated that he needed to carve the idols in complete darkness and requested that the door to the room be kept shut for twenty-one days without opening it. The Maharaja agreed, had the sculptor placed inside, and then locked the door, posting guards.

The Maharaja eagerly awaited the completion of the idols. After fifteen days, the queen remembered the sculptor. Worried whether he was alive or dead, she persuaded the Maharaja to check. They went to the sculptor's room, where the guards were posted, and the locks were intact. The Maharaja unlocked the doors and entered.

Inside, the sculptor was gone. There were three unfinished idols on three thrones. They were incomplete, as if a skilled artisan had left mid-work. The idols of Shri Krishna and his elder brother Balaram had two hands but no fingers. The idol of Subhadra, Shri Krishna's sister, had no hands at all. The divine wood had vanished from the spot. The Maharaja then built a grand temple on the seashore where the divine tree had appeared and consecrated the idols there. These idols, in one form or another, have been preserved to this day.

Conclusion:

The book provides a detailed historical and architectural overview of the Jagannathpuri temple, its spiritual significance, and the various rituals and festivals associated with it. It also touches upon the historical challenges and transformations the temple has undergone. The narrative emphasizes the unifying aspect of the Mahaprasad and the ideal of equality that the temple represents, while also acknowledging the societal realities that often fall short of these ideals. The inclusion of the mythological origin story of the idols adds a layer of religious narrative to the text.