Gyansar Astak Tatha Gyanmanjari Vrutti Part 3

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, broken down by the octets (Astak) discussed:

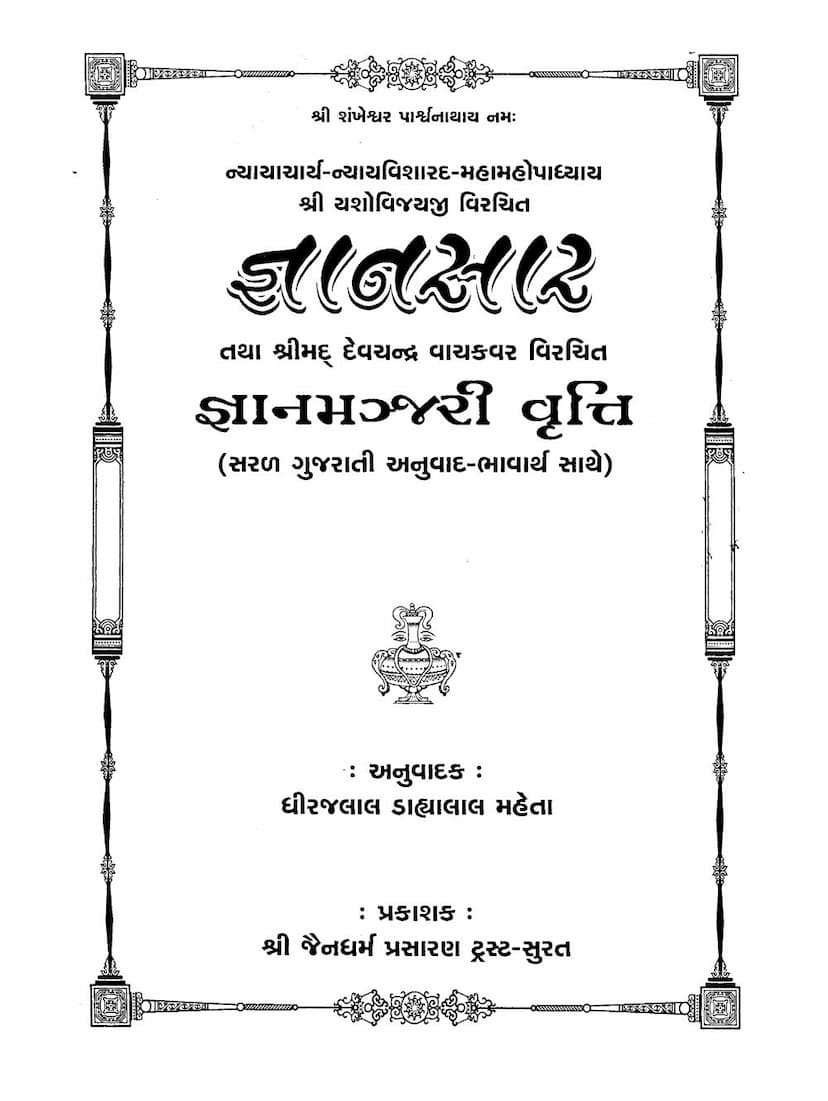

The text is part 3 of "Gyansar Astak tatha Gyanmanjari Vrutti" authored by Dhirajlal D Mehta, published by Shri Jain Dharm Prasaran Trust-Surat. It includes the commentary "Gyanmanjari Vrutti" by Shri Madhushri Devchandra Vachakvar on the works of Nyayacharya Shri Yashovijayji.

The provided pages focus on the "Madhyastha Astak" (Octet of Equanimity/Neutrality) and the beginning of the "Nirbhaya Astak" (Octet of Fearlessness) and the "Tattvadrishti Astak" (Octet of Vision of Truth).

I. Madhyastha Astak (Octet of Equanimity/Neutrality) - Astak 16

This section defines and elaborates on the concept of equanimity, a crucial virtue in Jain philosophy for achieving right meditation (Dharma Dhyana).

-

Definition: Equanimity is defined as a state of being unaffected by the combinations of auspicious and inauspicious situations, achieved by the discerning soul that has transcended attachment and aversion. A wise individual, through discriminative knowledge, does not develop attachment or aversion towards material substances or beings.

-

Four Types of Meditation (Dharma Dhyana): The text outlines four types of meditative states that form the basis of equanimity:

- Maitri (Friendship/Benevolence): Wishing that no living being commits sins, no living being suffers, and that the entire world be free from sins and suffering.

- Pramod (Appreciation/Joy): Having a profound sense of appreciation and joy towards the virtues of great souls who have eradicated all defects and possess insight into the true nature of reality.

- Karuna (Compassion): Having a disposition to help those who are helpless, distressed, frightened, or pleading for their lives.

- Madhyastha (Equanimity/Neutrality): Maintaining an attitude of indifference or detachment towards those who engage in cruel deeds, condemn deities or gurus, or praise themselves. This is not about apathy but about refraining from developing hatred.

-

Context from Yoga Shastra: The verses (118-121) defining these four states are attributed to Yoga Shastra.

-

Practical Application: It is emphasized that one should not develop attachment (Raga) towards auspicious qualities (like pleasant colors of matter) and aversion (Dvesha) towards inauspicious qualities. Instead, one should remain neutral. This applies to both pleasant and unpleasant situations arising from the interactions of beings.

-

Nishchaya Naya (Ultimate Truth Perspective): From the perspective of ultimate truth, equanimity means not being attached or averse to beings or substances that are inherently auspicious or inauspicious in their permutations.

-

Types of Equanimity:

- Dravya Madhyastha (Substantial Equanimity): Remaining neutral without engaging the soul's faculty of consciousness, devoid of seeking or means.

- Bhava Madhyastha (Modal Equanimity): The equanimity of a mendicant, achieved through a state of equanimous realization.

- Equanimity in Different Epistemological Standpoints (Naya): Equanimity is considered a substantial aspect when viewed from the first four standpoints (Nayavada) and a modal aspect when viewed from the last three pure standpoints.

-

Equanimity in Stages of Spiritual Progress (Gunasthana):

- Stages 6-12: These stages of practice involve meditative equanimity.

- Stages 13-14: These are stages of liberation, where the fully liberated souls (Siddhas) exhibit perfect equanimity (A-rakta-dvishtata - non-attachment and non-aversion) towards all beings and substances, which is the ultimate ideal.

-

Ethical Imperative: The text strongly advises against clinging to one's own viewpoint with prejudice (Kutarkas) and engaging in futile arguments or "childish mischief" (Balachapalya). Such debates lead to bitterness, animosity, and increased karmic bondage. Instead, one should strive for equanimity, detachment, and inner peace.

-

Mental Equanimity: The mind is likened to a calf following its mother (truth/logic) and a monkey pulling back the cow (truth/logic) with its tail due to stubbornness and prejudice. A balanced mind follows the path of truth, while a prejudiced mind distorts logic to support its own dogma.

-

Role of Nayavada (Viewpoints): All perspectives (Nayavada) are considered true within their own limited scope but false when they negate others. A wise sage maintains equanimity amidst these diverse viewpoints, understanding the relative truth of each without attachment.

-

Seven Nayavadas: The text begins to elaborate on the seven Nayas (Naisgama, Sangraha, Vyavahara, Rujusutra, Shabda, Samabhirudha, Evambhuta), categorizing the first four as Dravya Nayas (concerned with substance) and the last three as Bhava Nayas (concerned with modes). The explanation of Naisgama focuses on its ability to grasp both general and specific aspects of reality, often relating to the common understanding of the world.

II. Nirbhaya Astak (Octet of Fearlessness) - Astak 17

This section transitions to the concept of fearlessness, highlighting its connection to equanimity and the true nature of the self.

-

Foundation: Fearlessness is stated to arise from equanimity. A mind disturbed by emotions (fear, delusion) becomes restless. The true self, being pure consciousness and indestructible, is inherently fearless.

-

Types of Fearlessness:

- Nama & Sthapana Nirbhaya: Easy to understand (e.g., naming something "fearless" or creating an image representing it).

- Dravya Nirbhaya: Being free from seven types of fear.

- Bhava Nirbhaya: Being free from karmic bondage and emotional disturbances that lead to new karmic inflow and obscure the soul's true nature. These disturbances are considered the greatest fear as they obstruct the soul's innate qualities.

-

Fearlessness in Different Nayas:

- Naisgama: All substances are inherently fearless due to their permanent nature.

- Sangraha: The existence (Satta) of all things is eternal and indestructible, thus leading to fearlessness.

- Vyavahara: For the patient and calm individual unaffected by karmic results, fearlessness is observed.

- Rujusutra: For the mendicant (Nirgrantha) who has renounced all external possessions and attachments, fearlessness prevails.

- Shabda: The yogi absorbed in meditation, gradually destroying delusion, achieves fearlessness.

- Samabhirudha: The Kevalin (omniscient) is free from all delusions and thus fearless.

- Evambhuta: The liberated soul (Siddha) is inherently fearless, possessing all qualities in their pure, indestructible form, free from all eight types of karma.

-

True Source of Fearlessness: True fearlessness is achieved by those who understand their true self (Aatma) as pure consciousness and are detached from the results of their karma (audayika bhava). This understanding leads to the realization of fearlessness and ultimately to liberation.

-

Ethical Principles:

- Verse 1: Fearlessness leads to stability. Renounce childish arguments and cling to truth.

- Verse 2: Material pleasures (Samsara Sukha), tainted by numerous fears, are like ashes. True, unending happiness lies in the bliss of knowledge.

- Verse 3: The enlightened one, knowing their true self, has nothing to hide, claim, give away, or fear. Their knowledge is self-sufficient.

- Verse 4: The yogi with knowledge of the self as pure consciousness, unassailable by the "army of delusion," wielding the "weapon of knowledge," is like a king elephant in battle, fearless and triumphant.

- Verse 5: If the mind's vision (Jnana Drishti) roams freely in the "forest of the mind," like a peacock, the "serpents of fear" cannot coil around the "tree of bliss."

- Verse 6: He who wears the "armor of knowledge" that renders the "weapons of delusion" ineffective is untouched by fear or defeat in the "battle of karma."

- Verse 7: The ignorant, tossed by the "winds of fear," are like lightweight cotton; the wise, grounded in knowledge, remain unshaken.

- Verse 8: The yogi whose mind is characterized by faultless character (Charitra), fearlessly residing in the "kingdom of unbroken knowledge," possesses true fearlessness.

III. Tattvadrishti Astak (Octet of Vision of Truth) - Astak 19

This section emphasizes the importance of realizing the true nature of the self (Tattva) to overcome self-praise and achieve genuine spiritual progress.

-

Purpose: The text highlights that without the "Tattvadrishti" (vision of truth), one cannot overcome self-praise or the desire to hear it. This vision helps in eradicating ego and achieving inner peace.

-

Understanding Tattva: Tattva refers to the true nature of reality. For the soul (Jiva), Tattva is its essence of infinite consciousness. For non-soul substances (Ajiva), Tattva is their non-conscious nature. Tattva is the accurate, unbiased understanding of reality, free from partial viewpoints (Syadvada).

-

True Self: The ultimate Tattva for the soul is its pure, conscious form, which is unchanging, blissful, and possesses infinite knowledge and perception, unhindered by any external conditioning.

-

Types of Tattvadrishti (Based on Naya): Similar to equanimity, Tattvadrishti is explained through the lens of the Nayas, varying in depth:

- Naisgama: Sees the soul as fundamentally part of all things, capable of encompassing vastness.

- Sangraha: Focuses on the essential existence (Satta) of the soul, recognizing its omnipresence.

- Vyavahara: Perceives the soul through its mundane activities and experiences, seeing it as the experiencer of actions.

- Rujusutra: Sees the soul in its present existence, focusing on the immediate moment.

- Shabda: Perceives the soul through linguistic expressions and classifications.

- Samabhirudha: Recognizes the distinct meanings and nuances of different terms related to the soul.

- Evambhuta: Perceives the soul in its true, liberated state, embodying all its perfect qualities.

-

Practical Wisdom: The text contrasts external vision (Bahya Drishti) with the vision of truth (Tattvadrishti).

- Bahya Drishti: Gets deluded by external appearances (beauty, wealth, status, physical body, worldly possessions). It sees beauty in the external world and becomes attached.

- Tattvadrishti: Sees the true, unadorned nature of the soul. It perceives the physical body as a collection of impure elements (flesh, bones, fluids) and detached from the soul's essence. It finds bliss in the inner self, not in external glamour.

-

The Nature of Reality: External objects (like villages, gardens, beautiful forms) are perceived as sources of attachment and delusion by the worldly-minded but as objects of detachment and renunciation by the wise. Similarly, physical beauty is seen as divine by the unenlightened but as a mere vessel of impurities by the enlightened.

-

The Importance of Inner Vision: The text underscores that true richness lies not in external possessions (like chariots, elephants, royal courts) but in the inner qualities of the soul. The yogi, detached from external circumstances, possesses an inner wealth that surpasses any worldly grandeur.

-

The Yogi's Perspective: A yogi, grounded in spiritual knowledge, sees the soul's true nature as pure consciousness. They are not swayed by external appearances or worldly riches. Their inner state is likened to heavenly realms, while the worldly are deluded by temporary pleasures.

-

Self-Realization vs. External Achievements: The text emphasizes that true greatness comes from inner qualities (knowledge, equanimity, detachment) rather than external accomplishments or physical austerities. True sages are recognized by their inner wisdom and detachment, not by outward displays.

-

Critique of External Asceticism: The text critiques mere external practices like tonsuring the head, chanting mantras, or living in forests without inner transformation. True spiritualism lies in inner purity, knowledge, and equanimity.

-

The Goal: The ultimate goal is to transcend all external dependencies and attachments, realizing the soul's true, unadulterated nature, leading to liberation and eternal bliss.

IV. Sarva Samruddhi Astak (Octet of All-Pervading Prosperity) - Astak 20

This section discusses various forms of prosperity, ultimately pointing towards the ultimate spiritual wealth of the soul.

-

Definition of Prosperity: Prosperity (Samruddhi) is defined as comprehensive wealth. It encompasses mundane wealth (like wealth, kingdom, physical attributes) and supra-mundane spiritual attainments.

-

Types of Prosperity:

- Nama & Sthapana Samruddhi: Based on naming or symbolic representation.

- Dravya Samruddhi: Material wealth, kingdoms, and worldly powers achieved through virtuous deeds (Puṇya). This includes both Laukika (worldly, like Indra, Chakravarti) and Lokottara (supra-mundane, like the 16 Siddhis achieved by mendicants).

- Bhava Samruddhi: Spiritual wealth, the realization of the soul's inherent infinite qualities, achieved through shedding karma and attaining the ultimate state of liberation (Kshaya Labbhi).

-

The Sixteen Siddhis (Labbhis): The text lists sixteen types of spiritual powers or attainments, including various healing powers (Amrutosadhi, etc.), powers of movement (Charana Labbhi), knowledge of others' minds (Manaparyaya), omniscience (Kevalajnana), and royal powers like becoming Tirthankara, Chakravarti, Baladeva, Vasudeva.

-

Nayas and Prosperity: The text explains how each of the seven Nayas perceives prosperity:

- Naisgama: Sees prosperity in the potential causes and means for spiritual attainment.

- Sangraha: Recognizes prosperity in the inherent existence and potential of the soul.

- Vyavahara: Sees prosperity in the active pursuit and engagement in spiritual practices.

- Rujusutra: Focuses on present spiritual efforts and attainments.

- Shabda: Perceives prosperity through the correct use of spiritual terms and scriptures.

- Samabhirudha: Understands prosperity through the precise meaning and application of spiritual concepts.

- Evambhuta: Sees true prosperity in the fully actualized, liberated state of the soul, free from all karma.

-

Inner Wealth vs. Outer Wealth: The text contrasts worldly prosperity (like wealth, kingdoms, palaces) with the soul's inherent spiritual wealth (knowledge, bliss, equanimity). While worldly prosperity is dependent on external factors and subject to decay, spiritual prosperity is inherent, eternal, and self-sustaining.

-

Analogies:

- Indra's Prosperity: Indra's worldly enjoyments (Nandanvan, Vajra weapon, Indrani, Mahavimana) are compared to the yogi's inner spiritual wealth (Samadhi, Patience, Equanimity, Knowledge). However, Indra's wealth is external and fleeting, while the yogi's is internal and eternal.

- Chakravarti's Prosperity: The yogi, through detachment and spiritual discipline, surpasses the worldly might of a Chakravarti. While a Chakravarti uses outer shields (Charma Ratna, Chhatra Ratna) against external enemies (like Moha), the yogi employs inner spiritual qualities (knowledge, equanimity) to overcome inner enemies like delusion.

- Mahadeva's Analogy: The yogi, rooted in spiritual realization, adorned with the jewels of knowledge, patience, and equanimity, is likened to Lord Shiva, finding bliss in the divine realms of the self, unperturbed by worldly matters.

- Krishna's Analogy: The yogi, possessing the "eyes" of knowledge and perception (like the Sun and Moon), and having conquered the "hell of karmas," immersed in the "ocean of bliss," is no less than Lord Krishna.

-

The Ultimate Prosperity: The ultimate prosperity is the realization and embodiment of the soul's infinite, inherent qualities – Pure Knowledge, Pure Perception, Infinite Bliss, and Infinite Power – achieved through the shedding of all karmic obscurations. This is the true "Sarva Samruddhi."

This summary covers the key themes, definitions, analogies, and practical implications discussed within the provided text, highlighting the progression from equanimity to fearlessness and ultimately to the vision of truth and the realization of true spiritual prosperity.