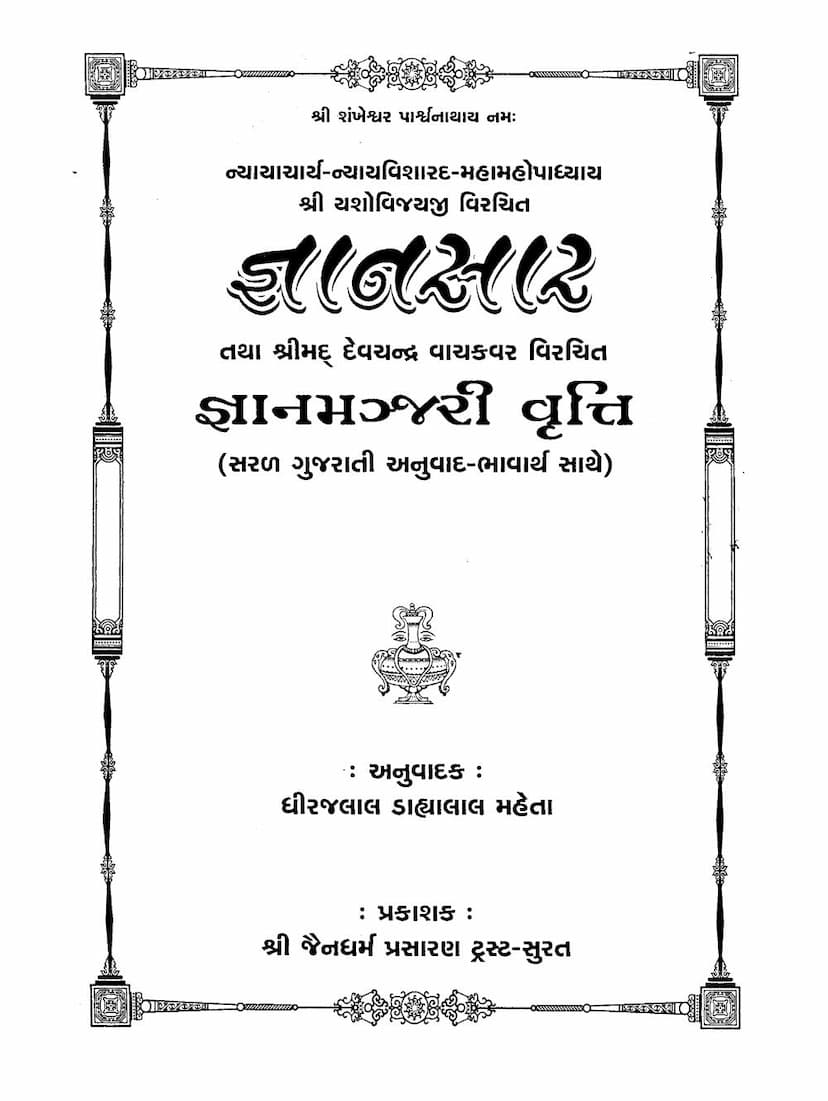

Gyansar Astak Tatha Gyanmanjari Vrutti Part 2

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Certainly! Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Gyansar Astak tatha Gyanmanjari Vrutti Part-2," focusing on the content of the provided pages:

Book Title: Gyansar Astak tatha Gyanmanjari Vrutti Part-2 Author: Dhirajlal D Mehta (for the translation/commentary), originally attributed to Shri Yashovijayji and Shri Madhudevachakvar for the primary texts. Publisher: Shri Jain Dharm Prasaran Trust-Surat

This text is part of a larger work, likely a commentary or translation of foundational Jain philosophical texts. The provided excerpt primarily focuses on the "Indriyajayaashtak" (Eight Verses on Sense-Control) and then transitions into the "Tyagastak" (Eight Verses on Renunciation) and briefly touches upon "Kriyastak" (Eight Verses on Action) and "Nihspruhashtak" (Eight Verses on Desirelessness) and "Maunashtak" (Eight Verses on Silence) and "Vidyashtak" (Eight Verses on Knowledge).

Here's a breakdown of the key themes and concepts covered:

I. Indriyajayaashtak (Chapter 7: Verses on Sense-Control)

- The Obstacle to Peace (Shama): The primary impediment to achieving a state of mental peace (Shama) is the intense desire for the objects of the five senses. The stronger the craving for sensory pleasures, the greater the attachment and aversion to desirable and undesirable objects, leading to the decline of equanimity.

- Victory Over Senses is Essential for Peace: To attain and maintain a state of mental peace, victory over the senses and their desires is paramount. This section aims to elaborate on the eight verses dedicated to this victory.

- The Nature of the Soul (Jiva) and Senses (Indriyas):

- Indra (Soul): The soul is referred to as "Indra" due to its inherent, boundless spiritual wealth and omnipotence, akin to the celestial king Indra.

- Indriyas (Senses): The senses are considered the "linga" (sign or indicator) of the soul. Just as the physical senses functioning correctly indicate the presence of life in a body, the senses are the signs of the soul's existence and its capacity to know.

- Proof of Soul's Existence: The senses' ability to perceive objects (like form, sound, smell, taste, touch) validates the soul's "jnayakatva" (knower-nature). This, in turn, supports the Jain principle that "Uvayo lakkhano jivo" (the soul is characterized by consciousness/cognition).

- Types of Senses:

- Dravya Indriya (Material Senses): These are the physical, material structures of the senses, made of subtle matter. They are further divided into:

- Nivritti Indriya (Sensory Organs): The physical structures of the senses formed by the results of specific karmic dispositions (like Angopanga Nama Karma and Nirmannama Karma). These are the observable parts like eyes, ears, nose, etc. They are further classified as:

- Bahya Nivritti (External Senses): The outward structures.

- Antar Nivritti (Internal Senses): The more subtle, internal mechanisms, minute parts of the body that are crucial for sensory function. The text uses the analogy of a sword (internal) and its sheath (external) where the sheath protects the sword but doesn't perform the cutting action.

- Upakarana Indriya (Instrumental Senses): The subtle supportive energies or faculties within the soul that aid the material senses without being directly consumed or destroyed by the act of perception. These are like the sharpness of a sword, enabling it to cut.

- Nivritti Indriya (Sensory Organs): The physical structures of the senses formed by the results of specific karmic dispositions (like Angopanga Nama Karma and Nirmannama Karma). These are the observable parts like eyes, ears, nose, etc. They are further classified as:

- Bhava Indriya (Modal Senses): These are the soul's inherent cognitive faculties.

- Labdhi Bhava Indriya (Potential Faculty): The potential or capacity to perceive sensory objects, arising from the partial removal (kshayopashama) of obstructing karmas like sensory-obstruction, specific-knowledge-obstruction, visual-perception-obstruction, non-visual-perception-obstruction, and energy-obstruction. This is like the skill to wield a sword.

- Upayoga Bhava Indriya (Actual Use/Perception): The actual process of knowing the sensory object, which is the fruit or result of the faculty. This is like the act of wielding the sword.

- Dravya Indriya (Material Senses): These are the physical, material structures of the senses, made of subtle matter. They are further divided into:

- The True "Subject" of Sensory Experience: The "subject" (vishaya) is not the object itself (like color or sound) but the subsequent mental modification (moha-parinati) of attachment (ishta) or aversion (anishta) towards it, driven by ignorance and passions. Knowledge is an attribute of the soul and not inherently binding. It is the attitude towards the object of knowledge (ishta-anishta buddhi) that creates bondage.

- The Goal: Conquest of Sensory Objects (Indriya Vishaya Jaya): The victory is over the desire and attachment/aversion to sensory objects, not the knowledge itself. This conquest leads to the mastery of the senses and the prevention of negative consequences stemming from unregulated sensory engagement.

- Types of Conquest:

- Dravya Jaya (Material Conquest): Involves physical restraint, controlling the senses, withdrawing from sensory indulgence, closing eyes, covering the body, etc. This is about controlling the external manifestations.

- Bhava Jaya (Modal Conquest): Involves directing the soul's consciousness and energy solely towards self-contemplation and the realization of its true nature, keeping it completely away from external influences. This is the internal victory.

- The Importance of Effort: The text emphasizes the need for immense effort ("sphārapauruṣam") to achieve victory over the senses, likening sensory pleasures to deadly poison (halāhala). It quotes Uttaradhyayana Sutra, highlighting how sensory desires lead to downfall.

- The Nature of Desire (Trushna): Desire is portrayed as an insatiable force, like rivers filling an ocean that remains unfulfilled. It's depicted as a poisonous tree growing from desires fueled by craving, offering the deadly fruit of delusion.

- The Unquenchable Thirst: Even Mount Kailash made of gold and silver wouldn't satisfy the greedy person; their desire is limitless like the sky. The text warns that sensory pleasures, repeatedly enjoyed and discarded by the wise, are merely refuse that the desire-filled soul still craves.

- The Futility of Sensory Gratification: The senses can never be satisfied. Just as a sea cannot be filled by thousands of rivers, the senses remain perpetually wanting. True contentment comes only from the soul's inherent qualities (shama and santosha).

- The Path to True Contentment: Contentment is achieved by turning inward, realizing one's own pure, blissful soul nature, and abandoning reliance on external, fleeting pleasures. The text warns against attachment to external things that lead to delusion and wandering in the cycle of birth and death.

- The Seven Perspectives (Nayas) on Sensory Control: The text outlines how different philosophical perspectives (Nayas) view sensory control, from the potentiality of physical form (Naigamanaya) to the actual realization of the soul's potential (Evambhuta-naya).

- Mati-Shruta Knowledge and its Role: The text connects the senses to the development of knowledge (Mati-Shruta). It states that the control of senses helps reveal the true nature of knowledge, which is an attribute of the soul, not an external object.

- The True Enemy is Moha (Delusion): The ultimate aim is not to conquer knowledge, but the delusion (moha) that arises from attachment and aversion to the objects of knowledge.

- The Analogy of Poisoned Milk: Just as pure milk is beneficial, but poisoned milk is harmful, knowledge mixed with delusion becomes a cause for transmigration and is considered a "vishaya" (subject) to be conquered.

- Examples of Sensory Attachment Leading to Doom: The text cites examples of moths drawn to flames (sight), fish to bait (taste), bees to fragrances (smell), elephants to she-elephants (touch), and deer to music (sound), all perishing due to a single sensory attachment. If one sense attachment is fatal, the consequence of attachment to all five is unimaginable suffering.

- The Importance of Self-Control and Inner Wealth: The text contrasts external sensory gratification with the inner wealth of the soul. True happiness lies in spiritual contentment and self-realization, not in fleeting worldly pleasures.

- The Power of Renunciation and the Goal of Liberation: The ultimate aim is liberation (moksha). This can only be achieved by renouncing sensory desires and focusing on the soul's true nature.

II. Tyagaashtak (Chapter 8: Verses on Renunciation)

- Renunciation as the Foundation of Victory: The conquest of the senses is achieved through renunciation. Therefore, the text moves to discuss renunciation as the next crucial step.

- Defining Renunciation (Tyaga): Tyaga means giving up or relinquishing. It is the abandonment of all "parabhava" (external states or substances) that leads to happiness.

- The Self is Eternal and Untouched: The soul's true nature (svadharma) is described as eternal, unchanging, and distinct from all external substances (pudgala). This true nature, though inherent, may be obscured by ignorance and attachment.

- The Concept of "Upadana" (Worthwhile) and "Heya" (To be Abandoned): The soul's true nature is "upadana" (worthwhile to pursue and realize), while all else is "heya" (to be renounced).

- Renunciation of External vs. Internal:

- Dravya Tyaga (Material Renunciation): Giving up external possessions, wealth, family, and even the physical body. This is a preparatory step.

- Bhava Tyaga (Modal Renunciation): The crucial renunciation of internal states like attachment, aversion, delusion, and all passions (kashayas). This is the true essence of renunciation.

- The Stages of Renunciation: The text outlines a progression:

- Abandoning negative external influences (like wrong beliefs, teachers, and paths).

- Renouncing beneficial external influences (like good associations, gurus, scriptures) once their purpose is served, as they are still external aids.

- Ultimately, renouncing even the subtle internal attachments and tendencies (vibhava) that veil the soul's pure nature.

- The Goal: Achieving Pure Soul Nature: The ultimate aim is to realize the soul's pure, unadulterated, and blissful nature, which is self-reliant and untouched by external influences.

- Analogy of the Sword and Sheath: The text uses the analogy of a sword (soul's potential) and its sheath (material senses) to illustrate the difference between the inherent potential and the external mechanism.

- The Seven Nayas (Perspectives) on Renunciation: Similar to the previous section, the text explains how different philosophical perspectives view the concept of renunciation.

- The Inner vs. Outer Self: The text distinguishes between the external self (bahiratma) – one who identifies with the body and worldly possessions – and the internal self (antaratma) – one who realizes the soul's true, pure nature. The journey from bahiratma to antaratma is a path of renunciation.

- The Ultimate State: Siddha (Liberated Soul): The ultimate goal is to become a Siddha, fully liberated from all karmic bondage, experiencing infinite bliss and consciousness.

- The Analogy of Poisonous Milk: Just as pure milk is nourishing, but poisoned milk is deadly, external pleasures, when mixed with attachment and delusion, lead to spiritual harm.

- The Unquenchable Fire of Desire: The text reiterates that desire is never satisfied. Even the greatest wealth cannot quench it. True satisfaction comes from within.

- The Examples of Renunciation: The text uses the examples of King Nami, Gaj Sukumar, and others who renounced worldly pleasures and power for spiritual liberation, demonstrating the profound impact of renunciation.

- The Need for Renunciation for Spiritual Growth: The ultimate aim is to attain the state of "Dharma Sanyasa," which is the renunciation of all external and internal attachments that hinder spiritual progress.

- The Analogy of the Lamp and Oil: Just as a lamp needs oil to burn, even the most knowledgeable person needs continuous spiritual practice (kriya) to maintain their spiritual state.

- The Nature of True Happiness: True happiness is found in the soul's self-realization and contentment, not in fleeting sensory pleasures.

- The Goal: Union with the Soul's True Nature: The journey of spiritual development involves shedding external identifications and embracing the soul's inherent, pure, and blissful nature.

III. Kriyashtak (Chapter 9: Verses on Action)

- Action (Kriya) as the Means to Liberation: The text emphasizes that purposeful action (kriya) is essential for spiritual liberation, stemming from the soul's own nature.

- The Role of Knowledge and Action: Liberation is achieved through the combined power of right knowledge (jnana) and right action (kriya).

- The Cycle of Samsara and its Cessation: The cycle of birth and death (samsara) is perpetuated by impure actions arising from delusion. Pure actions, like those leading to self-restraint (samvara) and karmic shedding (nirjara), are necessary to end this cycle.

- Types of Action:

- Dravya Kriya (Material Action): Physical actions, including those driven by pure intention and those driven by impure intentions (like harming others or seeking external benefits).

- Bhava Kriya (Modal Action): The intention and mental state behind the action. The soul's own effort and energy (virya) manifesting in action.

- The Nayas (Perspectives) on Action: Similar to previous sections, different Nayas are used to understand action, from the initial intention (Naigamanaya) to the actual realization of the soul's pure potential (Evambhuta-naya).

- The Importance of Right Intention: Actions are judged by their intention. Pure intentions (like devotion, study, penance) lead to positive results, while impure intentions (driven by ego, greed, or hatred) lead to further bondage.

- The Analogy of the Flame: The lamp's flame is inherently light-giving, but it requires fuel (oil) to continue burning. Similarly, even profound knowledge requires continuous practice and action to sustain and manifest its true potential.

- The Analogy of the Scratched Record: The text implies that actions, even those performed with pure intent, can be influenced by subtle karmic imprints, requiring constant vigilance and purification.

- The Ultimate Action: Realizing the Soul's True Nature: The highest form of action is the soul's complete absorption in its own pure, unchanging nature, transcending all external influences and desires.

IV. Nihspruhashtak (Chapter 10: Verses on Desirelessness)

- Nihspruha (Desirelessness) as the Reinforcement of Indriya-Nirodha (Sense-Control): The state of being untouched by external influences (Nirlepata) is strengthened by desirelessness (Nihspruhatva).

- Defining Nihspruhatva: The absence of desire for external objects or states, the eradication of longing.

- Types of Desirelessness:

- Nama Nihspruha: The mere utterance or thought of "desirelessness."

- Sthapana Nihspruha: Representing desirelessness through symbols or images (e.g., of renunciates).

- Dravya Nihspruha: Involves outward renunciation of possessions, wealth, and sensory comforts, often driven by a desire for future benefits or a misunderstanding of true renunciation.

- Bhava Nihspruha: The genuine absence of desire, rooted in the realization of the soul's true, self-contained bliss, which arises from understanding the nature of reality (Tattva) and the soul's inherent joy.

- The True Nature of Contentment: True contentment comes from within, from the soul's innate bliss, not from external possessions or sensory pleasures.

- The Insatiability of Desire: The text reiterates that worldly desires are never satisfied and lead to suffering.

- The Analogy of the Poisonous Tree: Desire is compared to a poisonous tree that yields only misery.

- The Wisdom of Renunciation: The wise abandon all worldly attachments and find true happiness in the soul's self-realization.

- The Importance of Discernment (Viveka): The text highlights the necessity of discerning between the real (soul) and the unreal (external), the permanent and the impermanent, to achieve true liberation.

- The Analogy of the Ant and the Mountain: The small ant is content with its meager existence, while the mighty elephant craves more. True contentment lies not in the quantity of possessions but in the quality of inner realization.

- The Futility of External Purity: The text warns against the illusion of achieving purity through external means like washing the body, as the soul's true purity comes from inner purification of thoughts and intentions.

- The Ultimate Source of Bliss is the Soul: True, lasting happiness and contentment originate from within the soul, not from external objects or sensory experiences.

V. Maunashtak (Chapter 11: Verses on Silence)

- The True Meaning of Silence (Mouna): Beyond mere abstention from speech, true silence (Mouna) lies in the stillness of the mind, the cessation of internal chatter, desires, and the control of sensory impulses (mind, speech, and body).

- The Soul's True Nature is Silence: The soul's inherent state is one of peace and stillness, free from the fluctuations of external desires and passions.

- The Power of Internal Silence: The text emphasizes that inner silence, the cessation of mental agitation and desires, is more profound and conducive to spiritual realization than mere external silence.

- The Goal: Stillness of Mind: The aim is to achieve a state of mental stillness, where the mind is not swayed by external sensory objects or internal passions.

- The Analogy of the Flame: Just as a flame flickers and wavers in the wind but remains steady when protected, the soul's consciousness, though tossed by passions, can find stillness through spiritual practice.

- The Importance of Restraining the Mind: The text stresses the need to control the mind's wandering tendencies and to direct its focus inward towards the soul's true nature.

- The Analogy of the Ocean: The mind is compared to the ocean, which can be calm and reflective or turbulent and agitated. True silence is like a calm, undisturbed ocean.

- The Path to True Silence: Achieving true silence involves detachment from external desires, controlling the senses, and cultivating inner peace through meditation and self-reflection.

- The True Mounī (Silent One): A true Mounī is not just one who abstains from speech but one who has achieved mastery over their mind, senses, and passions.

VI. Vidyashtak (Chapter 12: Verses on Knowledge)

- Knowledge as the Key to Liberation: The text emphasizes the crucial role of right knowledge (Vidya) in achieving liberation.

- Differentiating True Knowledge from False Knowledge: The text distinguishes between superficial or illusory knowledge (Avidya) and true spiritual knowledge (Vidya).

- The Nature of True Knowledge: True knowledge involves understanding the soul's true, eternal, and pure nature, differentiating it from the impermanent and impure external world.

- The Obstacles to True Knowledge: Delusion (Moha), ignorance (Avidya), and attachment to external objects are the primary obstacles to realizing true knowledge.

- The Path to True Knowledge: This involves discernment (Viveka) between the self and the non-self, introspection, study of scriptures, following the teachings of enlightened beings (gurus), and consistent spiritual practice.

- The Analogy of the Jewel Hidden in Mud: Just as a jewel hidden in mud retains its inherent brilliance, the soul's true nature remains untarnished by karmic impurities, awaiting rediscovery through knowledge.

- The Importance of Discernment (Viveka): The text highlights that the ability to distinguish between the real and the unreal, the permanent and the impermanent, is crucial for spiritual progress.

- The Path to Self-Realization: Through right knowledge and discernment, one can shed attachments to external, fleeting things and realize the soul's inherent, eternal bliss.

- The "Six Helpers" (Shatkarkas): The text delves into the philosophical concept of the six grammatical cases (Karta, Karma, Karna, Sampradana, Apadana, Adhikarana) as applied to the soul, illustrating how the soul is the agent, object, instrument, recipient, origin, and abode of its own actions and experiences.

- The Goal: Attaining the Pure Soul: The ultimate aim is to realize the soul's pure, unadulterated, and blissful nature, which is free from all karmic contaminations and eternal.

Overall Themes:

Across these "ashtakas," the overarching themes in the Jain tradition are evident:

- Self-Control: The paramount importance of controlling the senses and desires to achieve inner peace.

- Renunciation: The necessity of relinquishing attachments to external objects and internal passions for spiritual liberation.

- Right Action: The significance of performing actions with pure intentions, guided by right knowledge and ethical conduct.

- True Knowledge: The distinction between superficial and profound spiritual knowledge, with the latter leading to liberation.

- Desirelessness: The understanding that true contentment and happiness arise from within, not from external acquisitions.

- Silence/Stillness: The value of inner mental quietude and stillness for spiritual insight.

- Discernment: The critical ability to differentiate the eternal soul from the transient physical world.

- The Soul's True Nature: The inherent purity, bliss, and eternal nature of the soul, which is obscured by karma and delusion but can be rediscovered through spiritual practice.

The text, through its methodical explanation of these "ashtakas," aims to guide the reader towards a path of self-purification, detachment, and ultimately, liberation. The Gujarati translation and commentary make the complex philosophical concepts more accessible.