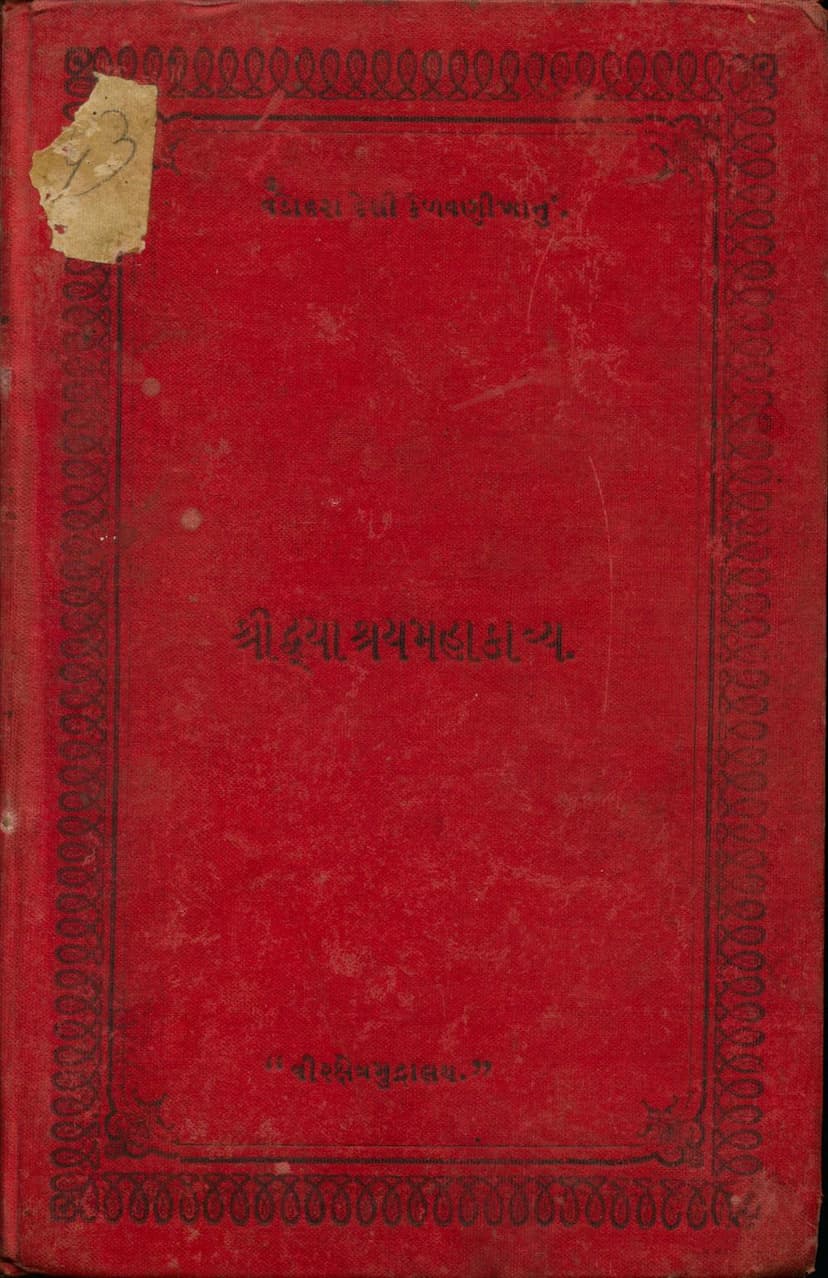

Dwashray Mahakavya

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Certainly, here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Dwāśray Mahākāvya" by Manilal Nabhubhai Dwivedi, based on the provided text:

Dwāśray Mahākāvya: A Summary of the Jain Text

The "Dwāśray Mahākāvya" is a significant Jain work translated and annotated by Manilal Nabhubhai Dwivedi. This summary is based on the introductory and summary sections of the provided text. The work itself, originally in Sanskrit, was commissioned by His Highness Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad, reflecting a commitment to promoting education and disseminating valuable ancient literature through regional languages.

Background and Purpose:

The project to translate and study rare and useful manuscripts from the Jain Bhandar in Patan was initiated by the Maharaja during a visit to the region. Recognizing the power of regional languages in spreading education, the Maharaja ordered the translation of important Sanskrit and English books into Marathi and Gujarati, or the creation of original works based on them. "Dwāśray Mahākāvya" was identified as one such significant text from the Patan Bhandar for translation. Manilal Nabhubhai Dwivedi was entrusted with this task and compensated for his work.

Summary of the "Dwāśray Mahākāvya":

The text is a vast historical epic, primarily focusing on the history and lineage of the Chaulukya (Solanki) dynasty, who ruled Gujarat. The summary provided outlines the content of its sixteen cantos (Sargs), highlighting key events, characters, and societal aspects:

-

Canto 1: Begins with praise for Syādvāda (Jain philosophy) and invokes blessings for the Chaulukya dynasty. It details the origin of the term "Chaulukya," linking it to the mythical birth of a hero from a handful of water (chuluka). The canto then delves into the history of Vikramānkadēva. It also touches upon the origin of the Paramara dynasty, linking them to warrior clans generated in conflicts. The lineage is traced back to the Sāma Vansh, and it's suggested that Bhāradvāja might be an ancestor. The canto primarily describes the capital city of Aṇahillapur and the early ruler Mūlarāja. The legend of the city's founding, linked to an Ahir named Aṇahilla, is presented, along with the tradition of establishing settlements in places frequented by cows.

-

Canto 2: The story of Mūlarāja continues. He receives a divine vision from Shankara instructing him to confront Grahari-pu (likely a ruler or demon tormenting the region of Saurashtra) who is hindering pilgrims to Prabhas Tirtha. The interpretation of "Grahari-pu" is discussed, with Forbes suggesting it might be a nickname. Mūlarāja, after waking and performing his rituals, summons his ministers Jabak and Jehul. He discusses his divine mandate to defeat Grahari-pu, citing the latter's atrocities against pilgrims and his own subjects. Jehul details Grahari-pu's cruel actions, including killing Brahmins and forcing women into concubinage. The ministers emphasize the need to eliminate him, highlighting his strong fortifications, the sea moat, and the support of allied kings and his powerful brother Lakṣarāja. Convinced, Mūlarāja prepares for a personal campaign.

-

Canto 3: Describes the onset of autumn, deemed suitable for military campaigns. The raja holds court, receives blessings from Brahmins, praises from bards, and auspicious ceremonies from women. After distributing alms, the king departs with his army, accompanied by several allied kings (Gōḍagrāma, Khallatika, Amadeśa, Śripēṇa, Harisiṁha). Rōhiṇīpēṇa leads the vanguard, with Śatabhiṣkṣēna and Punarvasusen on the flanks. The army camps on the banks of the Jambumālī river. The presence of Mūlarāja restores fearlessness to the people of Saurashtra.

-

Canto 4: Begins with the arrival of Kuṇas, a clever envoy of Grahari-pu, who questions Mūlarāja's purpose. Mūlarāja responds with righteous indignation, stating that he acts to alleviate the suffering of his subjects and protect dharma. He condemns Grahari-pu's actions, including hunting pregnant deer and consuming beef, declaring him an enemy who must be destroyed. The envoy relays this to Grahari-pu, who prepares his army, including powerful kings like Lakṣarāja of Kutch and Sindhurāja. Despite unfavorable omens, Grahari-pu advances to the Bhādar river, where Mūlarāja, advised by his Brahmin minister, also prepares to engage.

-

Canto 5: This canto details the battle. Kings like Rēvatī of Śilaprastha and Gāṁgama of Gaṁgadvāra, along with Bhilla and Kaśēna armies, fight on Mūlarāja's side. Kāśīrāja crosses the enemy lines, and Paramāra Arbhaśvara of Śrīmāla fights valiantly. Grahari-pu, seeing his army retreat, fights personally and pushes back Mūlarāja's forces. The battle rages for two days. Finally, Mūlarāja confronts Grahari-pu directly. Mūlarāja breaks Grahari-pu's mace with his śakti and destroys his arrow with a shot. Grahari-pu attacks Mūlarāja on his elephant with a sword, but Mūlarāja throws him down and binds him with the elephant's rope. Lakṣarāja intervenes but is defeated. Grahari-pu's wives plead for mercy, and Mūlarāja spares him after he cuts off his own little finger. Grahari-pu goes to Prabhas, worships Śankar, and returns to Aṇahillapur.

-

Canto 6: Concludes Mūlarāja's reign. He had a virtuous and brave son named Cāmuṇḍa. During a court session, various gifts arrive from different regions, including chariots, elephants, jewels, gold, and unique flowers. A fierce elephant sent by the king of Laṭa is presented, but Cāmuṇḍa declares it inauspicious. Mūlarāja, feeling insulted, orders the elephant back, and Cāmuṇḍa volunteers to fight Laṭa. Mūlarāja decides to accompany him. They cross the Sabarmati and Narmada rivers, causing panic in Bharuch. The kings of various regions (Puragāvana, Kēṭaravana, Sārikādhana, etc.) are sent to face Cāmuṇḍa. Mūlarāja, worried about his son fighting alone, follows. He sees the kings return unharmed, which he finds contemptible. However, they report that Cāmuṇḍa alone defeated Laṭa. Mūlarāja is overjoyed and upon Cāmuṇḍa's arrival, he proclaims his wish for the country's welfare, comparing it to the well-being of cows and their calves. Mūlarāja then abdicates in favor of Cāmuṇḍa, retires to Śr̥thaḷa on the banks of the Sarasvati, and immolates himself.

-

Canto 7: Details the reigns of Cāmuṇḍa and his sons Vallabharāja, Durlabharāja, and Nāgarāja. The text states Cāmuṇḍa reigned for ten years, but provides little detail about his reign. Forbes's account, based on Muslim historians, mentions Mahmud of Ghazni's destruction of Somnath, a fact not alluded to by Hemachandra. Forbes also suggests Cāmuṇḍa was licentious. The commentator on Dwāśray supports this by mentioning that Cāmuṇḍa's sister Vāvaṇīdēvī deposed him due to his misconduct and installed Vallabharāja. Cāmuṇḍa likely went to Kashi for penance, was robbed, and ordered Vallabha to attack Malwa. Vallabha died of illness during the campaign, his death kept secret by his commander. Durlabharāja then ascended the throne. He is noted for accepting Jainism and Syādvāda, refuting Ekāntavāda. Durlabharāja went to Marwar for his sister Durlabhadēvī's swayamvara, accompanied by his brother Nāgarāja. Forbes's account of Durlabharāja marrying his sister is not supported by Dwāśray. Durlabhadēvī rejected suitors like Angarāja, Kāśīrāja, Avantis, Cēdirāja, Kururāja, etc., choosing Durlabharāja. Mēha married Nāgarāja. On their return, they fought and defeated the aforementioned kings.

-

Canto 8: Narrates the prowess of Bhima, son of Nāgarāja. Astrologers predicted Bhīma's greatness. Durlabharāja offered the kingdom to Bhīma for spiritual pursuits, but Bhīma refused, questioning why he should be given the throne while his father was alive. Nāgarāja also refused, and together they enthroned Bhīma. Bhīma subdued the entire country, pacified enemies, and his dominion extended to the Yamuna and Magadha. He enforced strict laws, including punishing adultery. Spies reported that Sindhurāja and Cēdirāja were his enemies, plotting to kill him, and had gathered a large army. Bhīma, unable to tolerate this, consulted his ministers and marched with his army, halting at the river Pañcanada. He built a bridge, crossed, fought Sindhurāja in a duel, captured him, and returned.

-

Canto 9: Begins with Bhīmadēva's march towards Cēdi. Cēdirāja, upon hearing of Bhīma's approach, decided on a treaty. Bhīma's envoy, Dāmodara, arrived with a small army and was welcomed. He praised Cēdirāja's prosperity and righteousness, inquiring about their friendship. Cēdi King Karna decided it was proper to greet such a valiant king but was constrained by the custom of not crossing the Narmada. He sent gifts and a proposal of friendship through the envoy. Bhīma's ministers accepted the treaty. Bhīma entered the city, and later had two sons, Kṣēmarāja and Karṇa. Kṣēmarāja later had a son, Tribhuvanpāla. As Bhīma grew old, he offered the kingdom to Kṣēmarāja, who refused. The kingdom was then given to Karṇa, and Bhīma retired, eventually dying. Kṣēmarāja became a forest-dweller at Maṇḍukēśvara, and his son Tribhuvanpāla cared for him. Karn received the village Dhadhisthali near Maṇḍukēśvara. A painter showed Karṇa a portrait of Mayaṇallā, daughter of Jayakēśī of Candrapura (also called Mīṇaḷadēvī). The king fell in love, and Jayakēśī's people brought gifts to Karṇa's court. Jayakēśī sent his daughter, and Karṇa married her.

-

Canto 10: The king and Mayaṇallā had no children for many years. He performed severe austerities for Lakshmi's blessings. Lakshmi appeared, granting him dominion over all realms, but he asked for a son. Lakshmi granted his wish. Forbes claims Mayaṇallā was unattractive, and the king favored a dancer, only having a son due to a minister's trick. Hemachandra, however, describes the king and queen's mutual affection and the birth of their son.

-

Canto 11: Describes the birth of Simha (Jayasimha). Karṇa married Mayaṇallā, and their son Jayasinha was born. Astrologers predicted a bright future for him. He became skilled in warfare. Karṇa offered him the kingdom and intended to retire, but Jayasinha refused. Ultimately, Karṇa handed over the kingdom to Jayasinha, instructing him to care for Devaprasāda. Karṇa died, and Devaprasāda, with his son Tribhuvanpāla, also died shortly after, immolating himself on the Sarasvati bank. Jayasinha treated Tribhuvanpāla as his equal.

-

Canto 12: Brahmins from Siddhapura complained that demons had destroyed a charitable rest house built on the Sarasvati. The king, regretting his oversight, set out with his army. The demon king Babar, with a fierce army, attacked, throwing stones and trees. Jayasinha's army initially retreated but regrouped after the Pratihāras' encouragement and Jayasinha's personal intervention. Jayasinha confronted Babar, and though his sword broke, he subdued and captured him in hand-to-hand combat. Babar's wife pleaded for mercy, promising his reformation. Jayasinha released him, appointing him guardian of the place.

-

Canto 13: Jayasinha was out at night and overheard a conversation across the Sarasvati: one person would not live without the other and would follow them into a well. Jayasinha intervened, comforted the speaker, Kankachuda (son of Ratnachuḍa, loved by Vasuki), and inquired about his sorrow. Kankachuda explained a bet with his fellow student, Daman, over seeing Lōvli in winter. He lost his wife, and Daman was to go to Hul'uḍa, a Naga favored by Varuna, who threatened to drown the netherworld annually if not appeured. Kankachuda's task was difficult due to Kashmir's snowy climate. He sought Uṣa from a well to free himself from the bet, but his beloved wife wanted to accompany him. Jayasinha provided Uṣa and sent Kankachuda and his wife to Pātāla with his loyal attendant Babar.

-

Canto 14: Jayasinha encountered Yoginis during his night rounds, whom he aimed to defeat as they troubled the populace. The Yoginis advised him to appease Yashovarma of Avanti and make offerings. Jayasinha vowed to defeat Yashovarma and marched with a large army. He was met by Bhil soldiers. They camped near Avanti (Ujjain) and prepared to attack the fort. One night, Jayasinha saw the Yoginis creating an effigy of himself and performing rituals to ensure his defeat. He then attacked, defeating the Yoginis, including Kalika, who took various forms. Kalika, pleased, declared Jayasinha to be Vishnu and prophesied his victory over Yashovarma. Yashovarma fled to Dhara, but Jayasinha captured both Dhara and Avanti, imprisoning Yashovarma.

-

Canto 15: Concludes Jayasinha's reign. After defeating Yashovarma, he subdued many other rulers. He then initiated religious activities, repairing the Kedar route and constructing the Rudramahālay (Rudra-mal) in Siddhapura, along with a Jain temple. He visited Somnath on foot, worshipped there, and meditated in the temple, where Shankara appeared, granted him golden riches, and the epithet "Siddha." Shankara revealed that Kumārapāla, the son of Jayasinha's brother, would succeed him. After this, he passed away. Devaprasāda also immolated himself on the Sarasvati banks. Jayasinha treated Tribhuvanapāla, Devaprasāda's son, with great respect, considering him his equal.

-

Canto 16: Begins the history of Kumārapāla. Jayasinha did not indicate Kumārapāla as his successor, despite historical accounts suggesting otherwise. Kings from various regions, including Ānarta, planned to attack Gujarat. Ballala of Avanti conspired with southern kings to attack Gujarat when Kumārapāla was engaged with Ānarta. Key figures from Ānarta included rulers Baldi and Urden. Spies informed Kumārapāla of the impending invasion. He mobilized his army, including kings from Karkaṭaka, Pāṭaliputra, Mallavāste, etc., to face Ballala. He sent his general Kāka (a Brahmin) to fight Ballala with kings from Sāṁkāśya, Phālgūnīvah, Nāndīpura, and Vātānunnath. Kumārapāla himself marched towards Ānarta, joined by kings from Arāvat, Atri, Sāra, Darṣi, Sthala, Dhūma, Trigarta, Garta, etc. In Mâthu, he met his cousin Vikramasimha Parmār, who delayed him. Kumārapāla camped on the Banās river. The rest of the canto describes the seasons.

-

Canto 17: Continues describing the army's journey, focusing on their enjoyment of the seasons and water activities.

-

Canto 18: The march towards Ānarta resumes. Ānarta prepares to resist. An old minister advises against conflict with a former ally, but Ānarta, led by Govindarāja, decides to fight. Kumārapāla arrives. Ānarta emerges with long spears, like tall trees. The battle ensues. Ānarta's forces retreat, and he begins throwing chakras. Kumārapāla deflects them with arrows and brings his elephant close to Ānarta's. Kumārapāla strikes Ānarta with his śakti, causing him to fall. Kumārapāla spares him, taking his horses and elephants.

-

Canto 19: Continues the narrative. Kumārapāla remains on the battlefield to tend to the wounded. An envoy from Ānarta arrives, apologizes profusely, and requests Kumārapāla to maintain the friendly relationship his ancestors had. The envoy offers his daughter Jaṇā, along with her dowry and priest, for marriage. Kumārapāla accepts and requests the bride be brought to Aṇahillapur. He then releases prisoners and holds celebrations. The marriage ceremony takes place. Just as it concludes, a messenger from Kākasēnāpati arrives with news that Kākasēnāpati's generals, Vijaya and Kr̥ṣṇa, were defeated by Ballala through Abhijitya and Śāvitya. Kumārapāla's army retreated, but after the general's encouragement, they regrouped. The five kings accompanying Ballala defeated and killed him before the general could intervene. Hearing this, the king grants the messenger an award and takes the bride to his palace. He subjugates all his enemies.

-

Canto 20: Kumārapāla witnesses a man dragging dying goats to sell to a butcher. He condemns meat consumption and rebukes his father's legacy, believing people engage in such violence due to his own lack of discernment. He orders the punishment of those who break oaths, committing adultery, and causing violence to living beings. This decree is announced throughout the kingdom, even reaching Lanka. Those harmed are compensated with food for three years. He also prohibits alcohol consumption. In sacrifices, goats are replaced with grains. One night, hearing someone weeping, he finds a beautiful woman crying. She reveals she is the wife of a wealthy merchant whose husband and son died, leaving her property to the king, making her life meaningless. The king comforts her, promises not to confiscate her property, and advises her to perform religious duties. He then issues a decree to the same effect throughout the kingdom, pleasing the populace. A messenger informs him that King Khsa had let the Kedara temple fall into disrepair. Kumārapāla reprimands Khsa and orders his minister Vābhaḍ to repair the Somnath temple at Devapattana and the Pārśvanātha temple in Aṇahillapur. He receives a dream from Śambhu, who wishes to reside in his son. Consequently, he builds a temple for Kumārapāleśvara Mahādēva. Hemachandra's narrative in Dwāśray concludes here, with a blessing for Kumārapāla.

Special Observations:

- Historical Value: The text is considered invaluable for historical research, with its narrative being a primary source for Sir Alexander Kinloch Forbes's "Rāsamālā." The author highlights discrepancies between Forbes's and Hemachandra's accounts, emphasizing the need for accurate translations of Jain texts related to Gujarati history.

- Mahmud of Ghazni's Invasion: The author notes the absence of any mention of Mahmud's raid on Somnath in Hemachandra's work, contrasting it with Forbes's account, which relies on Muslim historians. The author speculates that the silence might be due to a desire to protect the reputation of the dynasty's heroes. He also points out that the mention of Somnath's destruction by Allāuddin during Karan Vaghela's time, as described in "Kāṇḍadēva Prabandha," suggests a potential second destruction. He concludes that definitively establishing the facts requires further illumination.

- Territorial Extent: The kingdom's borders appear vast, extending to Kolhapur in the south, Kashmir in the north, and Magadha beyond the Yamuna and Ganges in the east. Saurashtra was under its control, as was a portion of Sindh and Punjab. The names of many rulers are mentioned, but their identities are not always clear.

- Societal Norms and Practices: Dwāśray provides insights into the customs and practices of the time, including the political structure, the relationship between kings and subjects, the role of ministers, and the respect given to scholars. Warfare involved various weapons, and kings engaged in nightly patrols and employed spies. The text also details philosophical discussions and enumerates thirty-six types of knowledge. Military formations and alliances were common. The practice of keeping monkeys in stables for horses' eye health is mentioned, as is the use of swords made by embedding iron in a bird's egg. The education of princes included weaponry, wrestling, and archery. Kshatriyas were primarily weapon-wielders, but Brahmins also held positions of authority and engaged in warfare. Taxation methods and village administration are described, as are various festivals like Holi (explained through a demoness story), Bali Mahotsava, Navaratri, and Seemalanghana. The text also mentions games like Pañchikā and Chutamanjika.

- Religious Harmony: The text indicates the coexistence of Vedic and Jain religions, with worship of Vishnu, Shiva, Shakti, and Jinas. While religious debates occurred between Jain and Vedic followers, no king was shown to be fanatically attached to one religion over others. Kumārapāla, who promoted non-violence and adopted Jain practices, did not reject Vedic deities.

- Language and Style: The language is Sanskrit, described as pure but containing many regional words in both the text and its commentary. The text is considered difficult to understand without the commentary, and Hemachandra's poetic skill is noted as being of a lighter nature.

- Hemachandra's Biography: The author provides biographical details about Hemachandra, his birth, his initiation into Jainism, his rise to prominence, and his notable works. His death is attributed to various legends, but his scholarship as a grammarian and poet during the reigns of Siddharāja and Kumārapāla is undisputed.

In essence, "Dwāśray Mahākāvya" serves as a rich tapestry of history, philosophy, religion, and societal life during the Chaulukya period, making it an invaluable resource for understanding ancient Indian culture and governance.