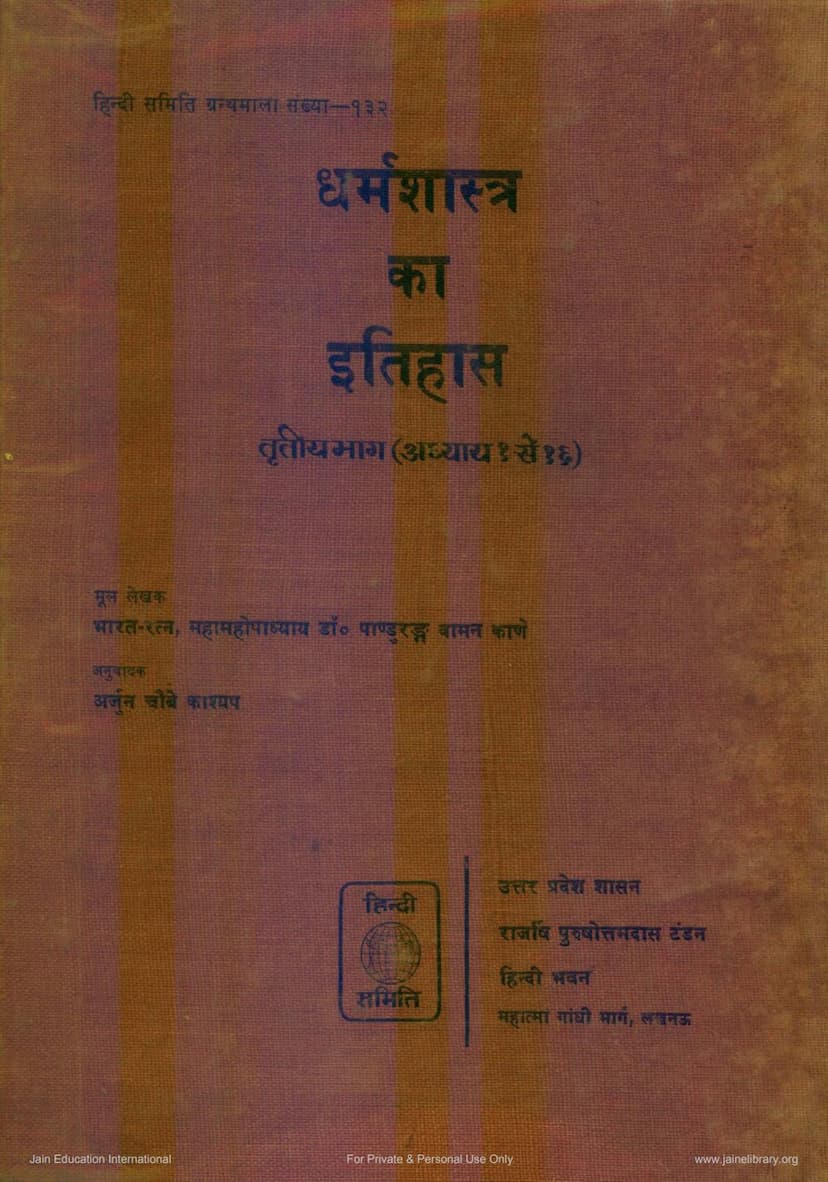

Dharmshastra Ka Itihas Part 3

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Dharmashastra ka Itihas Part 3" by Pandurang Vaman Kane, translated by Arjun Chaube Kashyap.

Overall Context:

The text is the third volume of a monumental work on the history of Dharmashastra, authored by the renowned scholar Pandurang Vaman Kane and translated into Hindi. This particular volume focuses on specific aspects of Dharmaśāstra, including sins (Pātaka), atonement (Prāyaścitta), the consequences of actions (Karma Vipāka), funerary rites (Antya Karma), impurity (Aśaucha), purification (Śuddhi), śrāddha rituals, and the significance of pilgrimage (Tīrtha). The book, published by Hindi Bhavan, Lucknow, is a detailed exploration of these themes within the context of ancient Indian legal and religious literature.

Key Themes and Chapters Covered:

The summary is structured around the chapters mentioned in the table of contents provided in the text:

-

Chapter 1: Pātaka (Sin/Crime):

- The chapter begins by acknowledging the diverse interpretations of "sin" across different religions, eras, and cultures. 0 It defines sin (Pātaka) as an act that violates divine law or goes against divine will, often expressed in sacred texts.

- The text traces the concept of sin in Vedic literature, noting the early awareness of wrongdoing and the desire to be sinless.

- A significant portion is dedicated to explaining the Vedic concept of Ṛta, which encompassed natural order, ritualistic correctness, and moral conduct. Violating Ṛta was seen as going against cosmic and moral law.

- Various Vedic deities like Mitra, Varuna, Surya, Agni, and Soma are discussed in relation to their roles as upholders or protectors of Ṛta.

- The Vedic understanding of sin evolved, with terms like āgas, enas, agha, durita, duṣkṛta, aṃhas, and vṛjina being used to denote different types of transgressions.

- The text notes the emergence of early classifications of sins, citing the Rigveda's mention of seven boundaries of wrongdoing and the Nirukta's enumeration of sins like theft, adultery with the guru's wife, drinking liquor, killing a Brāhmaṇa, etc.

- The concept of sin influencing one's actions and leading to negative consequences in this life or the next is explored, hinting at the later development of the theory of Karma and rebirth.

- The text also touches upon the philosophical question of the origin of sin in the human mind, referencing concepts like desire, anger, and greed, and the influence of the three Guṇas (Sattva, Rajas, Tamas) from Sāṅkhya philosophy.

- It highlights the human tendency to be conscious of their wrongdoings, even without fully grasping the philosophical underpinnings of sin's origin.

-

Chapter 2: Means to Reduce the Fruits of Sin (Pātaka-phalon ko kam karne ke sadhan):

- This chapter delves into the methods prescribed in Hindu scriptures to mitigate the consequences of sinful acts.

- Self-confession (Ātmāparādha-svīkaraṇa) is presented as a significant step towards purification, as described in the Apastamba Dharma Sutra and other texts, where confession was part of expiatory rituals.

- Remorse (Anutāpa) is emphasized as a crucial internal cleansing process, although it's noted that remorse alone might not be sufficient without external penances.

- Penance (Prāyaścitta) itself is discussed, with its etymology and various interpretations, signifying acts of atonement.

- Various penitential practices (Tapas) are listed, including fasting, repetitive recitation of Vedic mantras (Japa), performing Homa (fire rituals), and giving Dāna (charity).

- The text mentions the importance of Japa, particularly of Vedic hymns and mantras, as a means of purification, with emphasis on mental recitation (mānasa japa) being the most potent.

- Homa is presented as a ritualistic offering to deities to appease them and seek forgiveness, thereby purifying the individual.

- Charity (Dāna) is highlighted as a significant means of expiation, with various forms of donations like gold, cows, land, and grains being prescribed.

- Pilgrimage (Tīrthayātrā) is recognized as a spiritual journey that purifies sins, especially by bathing in sacred rivers like the Ganga.

- The chapter also touches upon the principle of Karma and Rebirth, where actions in this life determine future births and experiences, emphasizing that neither good nor bad karma can be escaped without its due fruition.

-

Chapter 3: Prāyaścitta (Atonement/Penance): Its Origin, Etymology, and Meaning:

- This chapter explores the term prāyaścitta and its historical evolution from Vedic literature.

- The Vedic term prāyaścitti and later prāyaścitta are discussed, with their meanings evolving from general atonement for ritual errors to a more specific concept of expiation for moral and ritual sins.

- The text analyzes the etymology of prāyaścitta, suggesting connections to terms like prāyaḥ (penance/austerity) and citta (mind/resolution), signifying a mental resolve for atonement through penance.

- The chapter discusses the debate on whether prāyaścitta can absolve sins committed intentionally (kāmataḥ) or only unintentional ones (akāmataḥ), referencing various scriptural opinions.

- The role of the king and learned assemblies (pariṣad) in prescribing and overseeing penances is highlighted.

- The text explains the concept of different types of punishments, including fines, physical punishment, and expulsion from society (jāti-daṇḍa), often intertwined with prāyaścitta.

- It acknowledges the vastness of literature on prāyaścitta, with entire chapters in Sutras and detailed discussions in later Smṛtis and Nibandhas.

-

Chapter 4: Specific Atonements for Specific Sins (Viśiṣṭa pāpoṁ ke viśiṣṭa prāyaścitta):

- This extensive chapter details the expiations prescribed for major sins (Mahāpātaka) and minor sins (Upapātaka).

- Mahāpātaka (Great Sins): The text elaborates on the five cardinal sins:

- Brāhmaṇahatya (Killing a Brāhmaṇa): Discussed extensively with various penances, including dwelling in the forest for years, carrying a skull, living on alms, and performing specific sacrifices. The severity of penance varied based on the Brāhmaṇa's knowledge and status.

- Surāpāna (Drinking Liquor): Differentiated based on the type of liquor and the caste of the drinker. For Brāhmaṇas, especially those versed in Vedas, drinking certain types of liquor was considered a great sin with severe expiatory requirements, sometimes even involving self-immolation in boiling liquor.

- Steya (Theft): Specifically highlighted is the theft of gold from a Brāhmaṇa, which constituted a Mahāpātaka. The value of the stolen gold and the caste of the owner determined the severity of the sin and the required penance.

- Gurutalpagamana (Adultery with Guru's Wife): Defined broadly to include relationships with the mother, wife of a spiritual teacher, daughter, and other close female relatives. The penances were severe, sometimes involving self-disfigurement or death.

- Association with Mahāpātakīs (Association with Great Sinners): Discussed the concept of guilt by association, where prolonged association with those who have committed Mahāpātakas could also lead to similar sinfulness, with varying degrees of penance based on the duration and nature of the association.

- Upapātaka (Minor Sins): A long list of minor sins is presented, including killing animals other than Brāhmaṇas, abandoning Vedic rituals, accepting a livelihood from prohibited sources, improper sexual relations, performing sacrifices for ineligible persons, selling forbidden items, neglecting duties, and various forms of dishonesty. The expiations for these sins were generally less severe than for Mahāpātaka.

- Other Sins: The text also touches upon sins like theft of other than gold, killing of forbidden animals, and various social transgressions, detailing their prescribed atonements.

-

Chapter 5: Names of Atonements (Prāyaścitta ke naam):

- This chapter provides a categorized list of various forms of penance and atonement described in the Dharmaśāstras.

- It details specific penances like Kṛcchra, Atikṛcchra, Cāndrāyaṇa (lunar penance), Parāka, Prāṇāyāma (breath control), Mahāsāntapana, Taptakṛcchra (penance involving consuming heated substances), and Śiśukṛcchra (penance for children).

- The text explains the methodologies and duration for performing these penances, often involving dietary restrictions, fasting, specific prayers, and ritualistic acts.

- It also mentions the concept of Pratyāmnāya, where alternative forms of penance, like donations of cows or money, were allowed for those unable to perform the prescribed austerities.

-

Chapter 6: Consequences of Not Performing Atonement (Prāyaścitta na karne ke parinaam):

- This chapter elaborates on the severe consequences for not performing the prescribed atonements.

- It emphasizes the belief in Naraka (hell), with detailed descriptions of various hellish realms and the tortures inflicted upon sinners based on their deeds.

- The concept of reincarnation is linked to unexpiated sins, stating that individuals are reborn into lower forms of life (animals, plants) or as humans with physical deformities and diseases as a result of their karma.

- The chapter discusses the Vedic and later Hindu understanding of the afterlife, the judgment by Yama, and the cyclical nature of birth, death, and rebirth (saṃsāra) driven by karma.

- It highlights the belief that unexpiated sins lead to suffering not only in this life but also in future lives.

-

Chapter 7: Antya Karma (Funerary Rites):

- This chapter begins by addressing the profound human question about life after death and the various beliefs surrounding it across cultures.

- It details the Vedic understanding of the post-mortem journey, the role of deities like Yama, and the importance of funeral rites.

- The text describes the various rites performed for the dying and the deceased, including the removal of the body from the deathbed, the purification of the body, the journey to the cremation ground, and the cremation itself.

- The importance of specific mantras and rituals associated with these rites is highlighted, with references to Rigvedic hymns (especially hymns from Mandala 10, Chapters 14-18) which are still recited during funeral ceremonies.

- The chapter discusses the practice of śrāddha offerings to the deceased ancestors and the concept of Prajāpati and Pitr̥ as divine figures associated with these rituals.

- It also delves into the complexities of funeral rites for different categories of people, such as āhitāgni (those maintaining sacred fires), women, children, and samnyāsins (renunciates).

- The practice of cremation (śmaśāna) and later burial (samādhi) are mentioned, with emphasis on the rituals performed at the cremation site.

- The text briefly touches upon the rituals for the deceased who died in foreign lands or under unfortunate circumstances.

-

Chapter 8: Śuddhi (Purification):

- This chapter focuses on the extensive concept of purification in Hindu Dharmaśāstra, covering various aspects of impurity and cleansing.

- It discusses Āśaucha (impurity/mourning period), which arises from birth (janma-āśaucha) and death (mṛtyu-āśaucha or śāva-āśaucha). The duration of impurity varied based on caste, the deceased's status, and the proximity of the relationship.

- The text details the rules for maintaining purity, including dietary restrictions, avoiding social contact, and specific ablutions.

- It covers the purification of the body, water, utensils, and places (homes, land).

- The varying opinions on purification methods, the role of time (kāla), place (deśa), and intent (hetu) are discussed.

- The chapter also acknowledges the emergence of practical relaxations in strict purity rules due to societal needs, particularly in the context of festivals or emergencies.

- The concept of Sadyah-śuddhi (immediate purification, often by bathing) is explained as an exception to the longer impurity periods in certain situations or for specific individuals like kings or those performing essential rituals.

-

Chapter 9: Śrāddha:

- This chapter is a significant and detailed exploration of śrāddha rituals, which are offerings made to deceased ancestors.

- It begins by defining śrāddha as an act of reverence towards ancestors, emphasizing the importance of śraddhā (faith/devotion) in its performance.

- The text traces the evolution of śrāddha from Vedic rituals like Pitr̥-Yajña and Ashṭakā to more elaborate forms described in later Smṛtis and Purāṇas.

- The concept of Pitṛ (ancestors) and their various categories (Kāvya, Barhiṣad, Agniṣvātā, etc.) and their perceived powers and influence on the living are discussed.

- The chapter explains the purpose of Śrāddha: to satisfy the ancestors, ensure their well-being in the afterlife, and invoke their blessings for the descendants (longevity, progeny, prosperity, spiritual progress).

- Eligibility for Performing Śrāddha: It details who is eligible to perform śrāddha, prioritizing sons, grandsons, great-grandsons, and then other male relatives, with specific rules for daughters' sons and even kings or priests in the absence of family.

- Eligibility of Brahmins for Hosting Śrāddha: A considerable portion is dedicated to the qualifications and disqualifications of Brahmins invited to partake in śrāddha feasts, emphasizing the importance of Vedic knowledge, virtuous conduct, and adherence to prescribed rules.

- Śrāddha Times: The auspicious times for performing śrāddha are discussed, including Amāvasyā (new moon day), Mahālaya, Ashṭakā, Anvaṣṭakā, Yugādi days, and Pitra-paksha (the fortnight dedicated to ancestors).

- Prohibited and Permitted Foods: The text lists various foods that are considered suitable or forbidden for śrāddha offerings, often highlighting the symbolic significance of certain items.

- The Role of Ritual Actions: The meticulous rules for performing śrāddha are described, including the preparation of the site, the making of pindas (rice balls), the offerings of water (arghya), the use of darbha grass, and the rituals involving Brahmins.

- Different Types of Śrāddha: The chapter differentiates between Pārvaṇa Śrāddha (performed on specific lunar days like Amavasya, involving multiple ancestors) and Ekoḍdiṣṭa Śrāddha (performed for a single deceased person, typically on their death anniversary or during mourning periods). It also mentions Vr̥ddhi Śrāddha (performed on auspicious occasions) and Sapiṇḍīkaraṇa (a ritual to unite the deceased with ancestors).

- The Concept of Sapiṇḍīkaraṇa: This crucial ritual, performed typically after the initial mourning period, aims to integrate the deceased into the lineage of ancestors, thereby uniting them in a common spiritual realm.

- Variations and Regional Practices: The text acknowledges that śrāddha practices varied geographically and across different Vedic śākhās (branches) and traditions.

- Modern Relevance: The author subtly hints at the gradual simplification and changing practices of śrāddha in modern times, noting that many complex rituals are no longer performed.

-

Chapter 10: Classification of Śrāddha (Śrāddhon ka vargīkaraṇ):

- This chapter seems to delve deeper into the categorization of śrāddha rituals, likely building upon the distinction between Nitya, Naimittika, and Kāmya śrāddha.

- It likely details specific types of śrāddha performed for different occasions or purposes, such as those for fulfilling specific desires or those performed on particular lunar days or constellations.

-

Chapter 11: Distribution of Śrāddha:

- This chapter focuses on the practical aspects of performing śrāddha, including the distribution of offerings and the sequence of rituals.

- It discusses the order of inviting Brahmins, the seating arrangements, the offering of arghya (water), the presentation of food (bali), and the final visarjana (farewell) rituals.

- The text might also address the order of precedence among different types of ancestors (e.g., paternal vs. maternal lineage) and the rituals associated with them.

Overall Significance:

Pandurang Vaman Kane's work, as represented by this volume, is an invaluable resource for understanding the historical development and systematic exposition of Dharmaśāstra. It meticulously details the evolution of concepts, the nuances of ritual practices, and the philosophical underpinnings of Hindu law and tradition. The translation into Hindi makes this vast knowledge accessible to a wider audience interested in the intricacies of Indian religious and legal history. The book highlights the comprehensive and evolving nature of Dharmaśāstra, reflecting societal changes and philosophical interpretations over centuries.