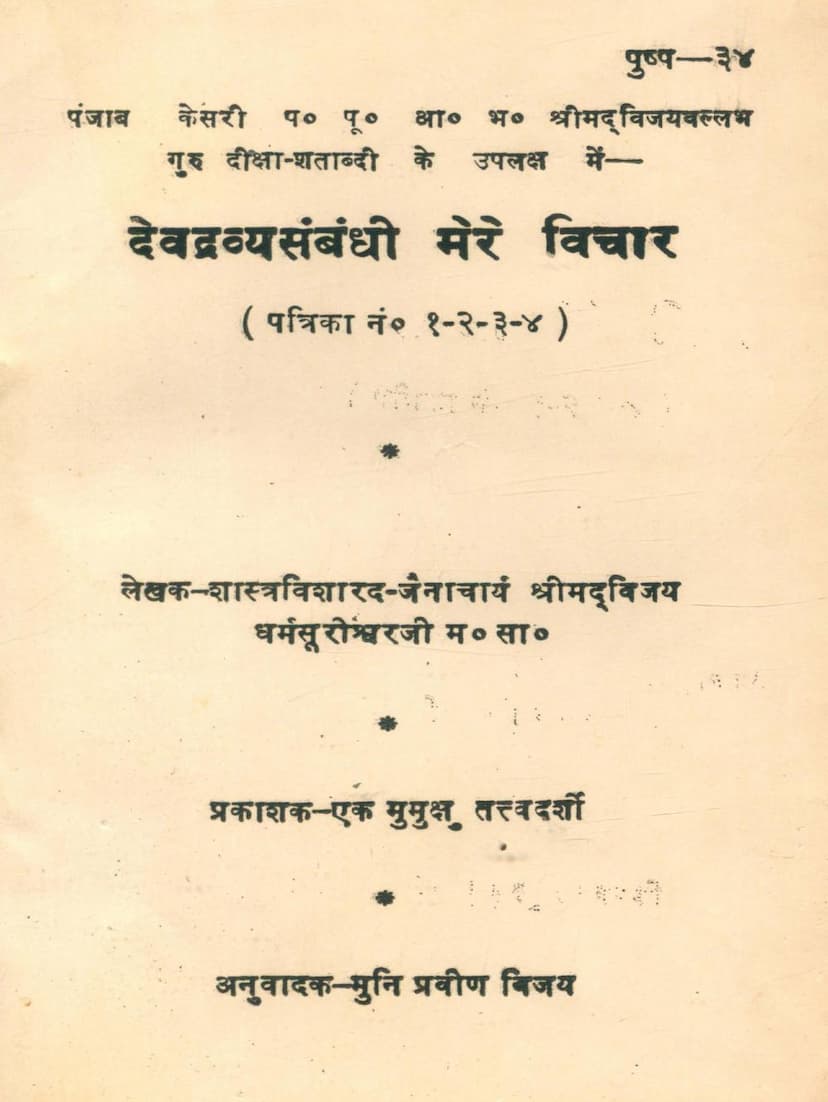

Devdravya Sambandhi Mere Vichar

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Devdravya Sambandhi Mere Vichar" (My Thoughts on Devadravya) by Acharya Shri Vijay Dharmasuri, translated by Muni Praveen Vijay:

Overall Theme:

This book, presented in a series of articles (patrikas), is a detailed discourse on the concept of "Devadravya" (wealth dedicated to deities) within Jainism. The author, Acharya Shri Vijay Dharmasuri, aims to clarify the nature of Devadravya, address the controversies surrounding its management and use, and propose a more rational and beneficial approach to its utilization for the welfare of the Jain community and its principles.

Key Arguments and Discussions:

Patrika No. 1: Introduction and the Problem of Devadravya Disputes

- The Problem: The author begins by lamenting the discord and disputes that have arisen within the Jain community regarding Devadravya. He observes that what should be a matter of spiritual devotion has become a source of conflict.

- Core Principle of Devadravya: The fundamental argument is that Devadravya is intrinsically linked to the "Murti" (idol or image of the deity). Any item offered with a spirit of devotion to the Murti constitutes Devadravya. Items not offered with such intention are not Devadravya.

- Historical Context: The author refutes the notion that ancient Jain temples were not in cities or lacked doors, citing historical descriptions of numerous temples in cities like Vaishali.

- Mismanagement and Misuse: A significant concern is the mismanagement of Devadravya. Trustees and "religious fanatics" are criticized for not adhering to the responsibilities associated with Devadravya, leading to its misuse in unrighteous activities.

- Unwise Practices: The book highlights the unauthorized lending of Devadravya on interest, which is against scriptural injunctions. If lending is unavoidable, it should be against collateral like ornaments.

- Cause of Disputes: The author identifies the excessive accumulation of Devadravya as a primary cause of disputes, leading to lack of transparency and accusations of misuse.

- Proposed Solution for Accumulation: To prevent this, the author suggests that any accumulated Devadravya should be judiciously spent on the renovation and maintenance of old temples. He notes that there are numerous temples in dire need of such work, which could absorb all collected Devadravya.

- Critique of Current Practices: The author criticizes the practice of diverting funds to business or earning interest, or even using them for appeasement of certain individuals, rather than for necessary upkeep.

- Re-evaluation of "Boli" (Bidding) Funds: A central proposal is to reclassify the income from "boli" (bidding for religious services like Aarti, Pujas, etc.) from Devadravya to a "Sadharan Khata" (general fund). This is because "boli" funds are not inherently dedicated to the idol or temple in the same way as directly offered items.

Patrika No. 2: The Flexibility of Religious Customs and the "Boli" Funds

- Change is Natural: The author emphasizes that customs and traditions evolve with time. Natural laws remain constant, but human-made customs can and should change based on circumstances.

- Changes in Jain Practices: He provides several examples of changes in Jain practices over time, such as the adoption of colored robes for monks (to distinguish from the lax), changes in the timing of Chaturmas based on Gurudev's orders, the shift from monks reading the Kalpa Sutra to it being read before the Sangha, and the change in the material of monks' staffs.

- "Boli" as a Human Invention: The author strongly argues that the practice of "boli" for religious acts is not a scriptural mandate but a custom introduced by the Sangha (community) for specific reasons.

- Purpose of "Boli": The primary purpose of "boli" was to prevent disputes and ensure smooth conduct of religious ceremonies, allowing the highest bidder to perform the first puja. This was to prevent conflict between individuals based on status or wealth.

- "Boli" is Not Devadravya by Definition: The author asserts that the funds generated from "boli" are not inherently Devadravya. He cites the example of offerings made during Anga Rachana (decoration of the idol), where ornaments are temporarily placed on the deity and then taken back, indicating a lack of permanent dedication.

- Reclassifying "Boli" Funds: Given that "boli" is a human-made custom and not intrinsically linked to Devadravya, the author reiterates that the Sangha can decide to transfer these funds to the Sadharan Khata.

- Benefits of Sadharan Khata: Funds in the Sadharan Khata can be used for all seven areas of religious expenditure, including supporting the needy, while Devadravya is strictly for temple and idol-related activities.

- Need to Strengthen Sadharan Khata: The author stresses the current need to strengthen the Sadharan Khata to support various community needs, especially in times of hardship.

- Historical Precedents for Change: The author provides numerous examples of how various religious income streams and practices have been reclassified or altered over time by the Sangha, demonstrating the permissibility of such changes.

- "Boli" funds as "Sadharan Dravy": He suggests that funds from "boli" can be considered "Sadharan Dravy" (general wealth) and used for the broader welfare of the community.

- Rejection of Fear of "Bhav-bhraman" (Cycle of Rebirth): The author dismisses the fear that changing customs will lead to negative karmic consequences, arguing that the spirit of the law and the context should be considered.

Patrika No. 3: How to Increase Devadravya

- The Basis of Devadravya is Intent: The author reiterates that the classification of wealth as Devadravya depends on the donor's intent at the time of offering. If an item is offered with the firm intention of dedicating it to the deity, it becomes Devadravya.

- Necessity of Devadravya: Devadravya is essential for the upkeep of idols and temples, including construction, renovation, ornamentation, and removal of any disrespect towards the deities.

- Scientific Methods of Increasing Devadravya: The author cites scriptural texts that describe various ways to increase Devadravya, such as offering new items, maintaining existing ones, investing judiciously, and avoiding activities that lead to its destruction or misuse.

- Importance of Righteous Means: It is emphasized that Devadravya should be increased through righteous means, avoiding illegal or unethical practices.

- Examples of Devadravya Increase: The book mentions practices like offering garlands, ornaments, new clothes, and lighting lamps as ways to increase Devadravya.

- Caution Against Misuse: The author strongly warns against using Devadravya for activities contrary to Jain principles or for personal gain. He cites scriptural verses that condemn such misuse, leading to negative karmic consequences.

- Distinction Between Devadravya and Sadharan Dravy: While Devadravya is strictly for temple-related purposes, Sadharan Dravy can be used for the seven areas of Jain expenditure, including supporting the needy. The author stresses that Sadharan Khata needs strengthening.

- The Concept of "Utsarpan": The author extensively analyzes the word "Utsarpan" from the Shraddhavidhi text. He argues that its meaning is related to offering, donating, or increasing wealth, not to "boli" or competitive bidding. He provides linguistic and scriptural evidence to support this interpretation and refutes the claim that "Utsarpan" implies "boli."

- "Boli" is not Scriptural: He reiterates that the practice of "boli" is a community-generated custom and not a scriptural injunction.

Patrika No. 4: Conclusion and Final Appeal

- Summary of Key Points: The author summarizes his main arguments: Devadravya is linked to the Murti and offered with specific intent. The practice of "boli" is a man-made custom, not scriptural, and its funds can be reclassified to the Sadharan Khata for broader community welfare.

- Addressing Criticism: He addresses criticisms against him, stating that his intention is not to abolish Devadravya but to ensure its proper utilization and to address community issues.

- Emphasis on "Samayagna" (Awareness of Time and Context): The author repeatedly stresses the importance of understanding the time, place, and specific circumstances when applying religious principles.

- Call to Action: He urges the Jain community, particularly the Sanghas in villages and cities, to make informed decisions, re-evaluate traditions, and prioritize the strengthening of the Sadharan Khata. He encourages the use of accumulated Devadravya for temple renovations.

- The Power of Intent: The core message is that the ultimate determinant of any wealth's classification and karmic consequence is the donor's intent.

- Openness to Discussion: The author expresses his willingness to change his views if presented with irrefutable scriptural evidence.

- The Importance of Sadharan Khata: He concludes by emphasizing that strengthening the Sadharan Khata is crucial for the Jain community's welfare and its ability to propagate the teachings of Lord Mahavir.

In essence, the book is a call for a more rational, scripturally grounded, and community-oriented approach to managing Jain religious funds. It challenges unquestioned adherence to traditions and advocates for change when necessary, prioritizing the welfare and spiritual growth of the Jain populace.