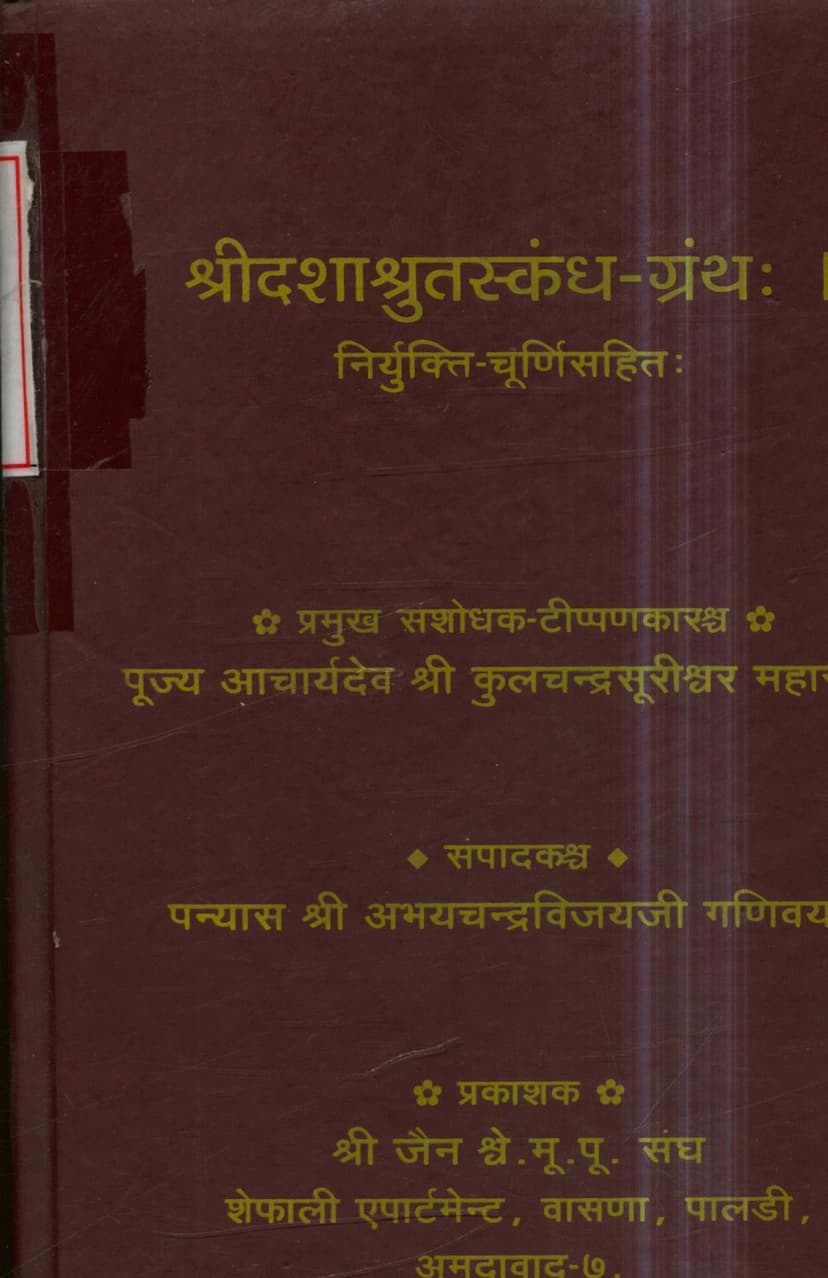

Dashashrut Skandh Granth

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

The provided text is the "Dashashrut Skandh Granth," authored by Kulchandrasuri and Abhaychandravijay, and published by the Jain Shwetambar Murtipujak Sangh. It is a significant Jain text that delves into various aspects of Jain philosophy and practice, structured into ten "Dashas" (sections or stages). The text includes commentary (Niyukti and Churni) and is presented with extensive research and annotations by Acharya Kulchandrasuri.

Here's a summary of the content based on the provided pages:

Overall Structure and Purpose:

The book focuses on the "Dashashrut Skandh," which appears to be a text detailing ten stages or states of human life, particularly from a Jain perspective. The commentary and annotations aim to clarify and elaborate on the original teachings, making them accessible for study and practice. The overall intention seems to be spiritual upliftment and the removal of obstacles in the path of liberation.

Key Themes and Content Breakdown by Dashas (as inferred from the text):

-

Introduction and Gratitude (Pages 1-3): The initial pages express gratitude to the lineage of Acharyas who imparted the knowledge of the six Cheda Sutras and specifically the Dashashrut Skandh. The editor, Panṇyās Abhaychandravijay, expresses his aspiration for spiritual progress and purity of conduct.

-

Dasha 1: Asamādhi-sthāna (States of Non-Equanimity/Disorder) (Pages 4-6, 34-48):

- This Dasha is based on the "Dashashrut Skandh," which outlines ten stages of human life in relation to lifespan. These are described as childhood (Bala), slow development (Manda), playful (Krida), strong (Bala), intelligent (Pragna), weak (Hayani), problematic (Prapancha), stooped by burden (Pragbhara), mumbling (Manmukhi), and inert (Sayani).

- The text clarifies that these are lifespan-related stages. However, the Dasha itself outlines ten stages related to the study (Adhyayana), which are: Asamādhi (non-equanimity), Sabala (strong/mixed character), Ashatanā (disrespect/offense), Gaṇi-guṇa (qualities of a leader/teacher), Manaḥ-samādhi (mental equanimity), Shravaka-pratimā (lay disciple's vows), Bhikshu-pratimā (monk's vows), Kalpa (rules/regulations), Moha (delusion), and Niydān (desires for future gain).

- The first Dasha specifically deals with twenty Asamādhi-sthāna, described by Bhadrabahuswami. These include hastiness in actions, uncleaned conduct, impure conduct, excessive possessions, disrespect towards elders, harming living beings, anger, ego, slander, repeatedly causing distress to others, creating new conflicts, reviving old ones, inappropriate study, impure movements of limbs, hasty speech, creating discord, abusive language, excessive eating, and causing agitation to others. These lead to a mixed or impure character.

-

Dasha 2: Sabala (Mixed Character) (Pages 6-7, 48-52):

- This Dasha deals with twenty-one "Sabala-sthāna," representing various impurities or lapses in conduct. These include improper use of limbs, sexual misconduct, eating at night, consuming ritually impure food (Ādhākarma), accepting money, using things obtained through improper means, repeatedly breaking vows, changing monastic groups within short periods, excessive bathing, deceit, using laypeople's alms, harming the six types of living beings, speaking falsely out of attachment, stealing out of attachment, using impure earth for bedding or sitting, using impure wood, living/sitting/standing on places with living beings or their products, consuming roots, bulbs, bark, fruits, flowers, seeds, leaves, and plants, touching water or crossing rivers excessively, and engaging in anger, pride, deceit, and greed.

- These are described as turning a monk's character into something like a mixed-colored cloth.

-

Dasha 3: Āshatanā (Offenses/Disrespect) (Pages 7-8, 52-59):

- This Dasha details thirty-three offenses or acts of disrespect. These are categorized into those related to avoiding falsehood (Mithyā-varjana-rūpa) and those related to gain (Lābha-rūpa). The latter is further divided into six types.

- Acts of disrespect are elaborated in terms of substance, place, time, and mental state. The text emphasizes that a monk who does not avoid these offenses cannot attain spiritual virtues or liberation.

-

Dasha 4: Gaṇi-sampada (Qualities of a Leader/Monastic Head) (Pages 8-9, 59-69):

- This Dasha discusses the qualities and responsibilities of a spiritual leader (Gaṇi). It outlines eight types of "sampada" (accomplishments/virtues): Āchāra-sampada (conduct), Shruta-sampada (scriptural knowledge), Sharīra-sampada (physical health/appropriateness), Vachana-sampada (speech), Vāchanā-sampada (teaching/recitation), Mati-sampada (intellect), Prayoga-sampada (application/skill), and Sangraha-parinnā (comprehension of collection/management).

- It also details four types of discipline (Vinaya): Āchāra-vinaya, Shruta-vinaya, Vikshepanā-vinaya (broadcasting/propagation), and Dosha-nirghātana-vinaya (removal of faults). Each of these is further broken down into four sub-categories, highlighting the multifaceted responsibilities of a leader in guiding disciples and the community.

-

Dasha 5: Chitta-samādhi-sthāna (States of Mental Equanimity) (Pages 9-11, 69-78):

- This Dasha focuses on achieving mental equanimity, emphasizing its importance as all spiritual activities are futile without it.

- The text describes ten mental states or stages leading to or maintaining equanimity. These are presented in relation to acquiring higher spiritual knowledge and states, including: Dharma-chintā (contemplation of Dharma), Saṁjñī-jñāna (knowing with true consciousness), Svapna-darshana (dream interpretation), Devārchī-darshana (seeing divine beings), Avadhi-jñāna (clairvoyance), Avadhi-darshana (clairvoyant perception), Manaḥ-paryavajñāna (telepathy), Kevala-jñāna (omniscience), Kevala-darshana (omniscience perception), and Kevala-maraṇa (liberation/ultimate death).

- The Dasha includes detailed descriptions of how one attains these stages, often through ascetic practices and the eradication of passions.

-

Dasha 6: Upāsaka-pratimā (Lay Disciple Vows/Stages) (Pages 11-14, 80-90):

- This Dasha elaborates on the eleven stages or vows undertaken by lay disciples (Upāsaka) in Jainism.

- It begins by contrasting the views of Ākriyāvādins (nihilists/atheists) with Kriyāvādins (believers in action and consequence). The Ākriyāvādins are depicted as adhering to extreme materialism, denying the spiritual realm, divine beings, and the fruits of actions.

- The eleven Upāsaka-pratimā are then detailed, outlining progressively stricter observances, including the gradual renunciation of worldly activities, fasting, and celibacy. The text provides specific details on the nature of these vows and their duration.

-

Dasha 7: Bhikshu-pratimā (Monastic Vows/Stages) (Pages 14-18, 90-108):

- This Dasha focuses on the various stages of monastic practice, known as Bhikshu-pratimā.

- It describes twelve such stages, starting with monthly (Māsikā) and extending to various combinations of multi-monthly and nightly observances, culminating in a one-night (Ek Rātrikā) observance.

- The text details the specific rules and practices associated with each pratimā, including dietary restrictions, conduct, methods of contemplation, and the handling of even minor impurities. It emphasizes strict adherence to these rules and the severe consequences of their violation.

-

Dasha 8: Paryuṣaṇā-kalpa (Rules of the Paryuṣaṇā Period) (Pages 18-27, 108-131):

- This Dasha is dedicated to the rules and observances during the Paryuṣaṇā period, the most important festival in Jainism.

- It explains the meaning and origin of the term "Paryuṣaṇā" and its various interpretations.

- A significant portion details the "Kalpasthāpanā" (establishment of rules) regarding the monsoon retreat (Chātumāsā). This includes the concept of "Avagraha" (restraint in terms of distance) in different directions and for different durations.

- The text discusses various reasons for extending or shortening the retreat, such as the condition of the land (muddy), availability of alms, royal decrees, and natural calamities.

- It provides specific rules for monks regarding their movement, the acceptance of alms, the use of materials, and the importance of equanimity during the retreat. The narrative of Acharya Kalaksuri's decision to observe Paryuṣaṇā on the fourth day due to King Shātavāhana's festival is recounted, explaining the origin of a particular practice.

-

Dasha 9: Mohaniya-sthāna (States of Delusion/Deluding Karma) (Pages 31-32, 144-153):

- This Dasha focuses on the thirty Mohaniya-sthāna (causes of delusion or delusion-producing karma). It explains how monks, by indulging in certain actions and mental states, bind themselves to Mohaniya karma, leading to a difficult path to enlightenment.

- These states include violence, falsehood, deceit, stealing, lust, greed, slander, and disrespect towards divine beings or the teachings. The text emphasizes the importance of understanding and overcoming these states to progress spiritually.

-

Dasha 10: Pāpa-nidāna-sthāna (Pap-Nidāna/Sinful Desires) (Pages 32-33, 153-167):

- This Dasha describes nine types of "Nidāna" (desires or vows made for worldly gain, often with a karmic consequence). These are categorized into those related to human desires (desiring a beautiful form, human pleasures) and those related to divine states (desired heavenly pleasures).

- The text details how these Nidanās can lead to unfavorable rebirths and hinder spiritual progress. It stresses the importance of being "Nirnidāna" (free from such desires) for achieving liberation. The examples of King Kōṇika and King Śreṇika are used to illustrate the context of these teachings.

Editorial and Scholarly Contributions:

The text highlights the significant contribution of Acharya Kulchandrasuri as the chief researcher and commentator, and Panṇyās Abhaychandravijay as the editor. This suggests a scholarly approach to presenting the ancient text, with efforts made to provide context, explanation, and critical analysis.

In essence, the Dashashrut Skandh Granth, through its ten Dashas, provides a progressive spiritual roadmap for Jain practitioners, detailing the stages of life, ethical conduct, monastic discipline, and the path to overcoming worldly afflictions and achieving liberation.