Dandakvichar

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This Jain text, "Dandakvichar" (also referred to as "Vichar Shat Trishika"), is a detailed discourse on the classification of living beings into different "dandakas" (categories or states of existence) and their attributes according to Jain philosophy. The work is published by Atmanand Jain Sabha, Bhavnagar, and is attributed to the teachings of Atmanandji.

Here's a comprehensive summary of the content, based on the provided pages:

I. Introduction and Dedication (Pages 1-2):

- The initial pages feature images and dedications related to the Atmanand Jain Sabha and the Shri Mahavir Jain Aradhana Kendra.

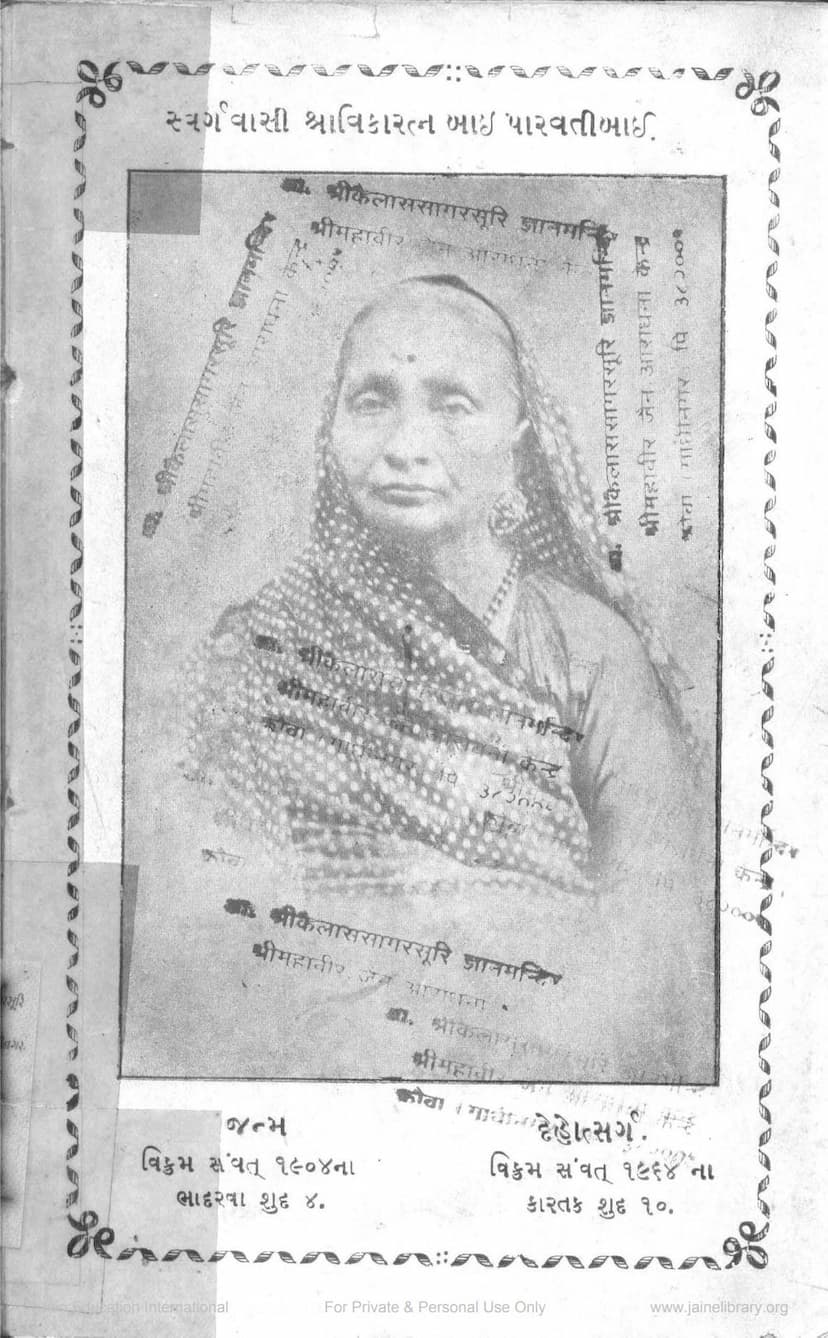

- There's a mention of "Shrāvikaratna Bai Parvatibai," indicating a biographical element or a dedication to a devout laywoman.

- The birth and death anniversaries of someone are noted, suggesting the book might be a memorial publication.

II. Biography of Bai Parvatibai (Pages 3-5):

- This section provides a biographical sketch of Bai Parvatibai, a devout Jain laywoman.

- She was born in Vikram Samvat 1904 (1787 AD) on the fourth day of the bright half of Bhadrapada, coinciding with the auspicious day of Samvatsari.

- From childhood, she exhibited strong religious devotion and possessed qualities like sweetness in speech, purity of heart, simplicity, forgiveness, and peace.

- She was particularly characterized by her compassion, extending private charity of thousands of rupees annually to the poor. She also contributed significantly to religious activities like pilgrimage, serving congregations, and devotion to monks and nuns.

- She was married in Vikram Samvat 1918 (1811 AD) to Seth Motichand Devchand, described as a virtuous, compassionate, and religious person who achieved business success and used his wealth for religious purposes.

- Bai Parvatibai passed away in Kartik month of Vikram Samvat 1994 (1937 AD), leaving behind her husband and four sons.

- Her husband, Seth Motichand Devchand, donated a sum of Rs. 15,000 for religious activities in her memory.

- The text encourages Jain women to read and emulate the lives of such exemplary women.

III. Publisher's Note and Explanation of the Text (Pages 6-8):

- This section explains the origin and purpose of publishing the "Dandakvichar."

- The text is described as a part of "Dravyānuga," which is a principal branch of the Jain philosophical concept of "Shad-dravya" (six substances).

- The original work was completed in Vikram Samvat 1570 (1513 AD) in Patan city by Muni Gajasar, a disciple of Upadhyay Shridhavalchandra, who was part of the lineage of Acharya Jinhansuri.

- The Sanskrit of the original work is praised for its simplicity and engaging nature, making it easy to memorize.

- The published version includes the original text with its commentary and a translation for wider accessibility.

- The book is presented as an annual gift to the subscribers of "Shri Atmanand Prakash."

- Seth Motichand Devchand, of Mangrol, residing in Mumbai, is thanked for his generous donation to make the publication possible in memory of his wife. The act of supporting knowledge dissemination in memory of a loved one is highlighted as a noble deed.

- The publishers request readers to point out any errors and express their gratitude for any corrections.

IV. The "Dandakvichar" Text (Pages 9 onwards):

This is the core of the book, detailing the classification of souls (jivas) into 24 dandakas and analyzing various aspects of their existence.

-

Invocation (Page 9): The text begins with an invocation to the Tirthankaras, specifically Lord Parshvanath, and a declaration of intent to explain the "Vichar Shat Trishika" with a simplified commentary for beginners.

-

The 24 Dandakas (Pages 10-13):

- The author salutes the 24 Tirthankaras and states the intention to briefly describe the 24 padanus (terms or concepts) within each of the 24 dandakas.

- The 24 dandakas are listed and explained:

- Naraki (hellish beings) - 1 dandaka (covering the seven hells).

- Asuras and other nine types of celestial beings (Navanpatic): 10 dandakas.

- Earth-bodied (Prithvikaya) and other stationary beings (Sthāvara) - 5 dandakas (earth, water, fire, air, and plant-bodied).

- Two-sensed, three-sensed, and four-sensed beings (Viklendriya): 3 dandakas.

- Garbhaja (born through conception) Tiryanch (animals) and Garbhaja Manushya (humans): 2 dandakas.

- Vāntara (planetary) and Jyotishika (luminous) celestial beings: 1 dandaka each.

- Vaimānika (celestial beings residing in chariots) celestial beings: 1 dandaka.

- Total: 1 + 10 + 5 + 3 + 2 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 24 dandakas. (Note: There might be slight variations in how some categories are counted, leading to the 25 "jivasthanas" mentioned in some contexts).

-

The 25 Attributes/Dwaras (Pages 13-46): The text then systematically analyzes 25 aspects or "dwaras" (gates/attributes) for these dandakas. These include:

- Body (Sharira): Types of bodies (Audārika, Vaikriya, Āhārika, Taijasa, Kārmana).

- Incarnation/Height (Avagahana): Minimum, medium, and maximum height.

- Bone Structure/Constitution (Samhanana): Six types of bone structures.

- Consciousness/Sentience (Sanjna): Four or ten types of consciousness (nourishment, fear, mating, possession, and others like anger, pride, deceit, greed).

- Form/Posture (Samsthana): Six types of forms.

- Passions (Kashaya): Four main passions (anger, pride, deceit, greed).

- Leshya (Auras/Colors): Six types of leshyas (black, blue, peacock-colored, fire-colored, lotus-colored, white), with nuances for different dandakas.

- Sense Organs (Indriya): Five sense organs (touch, taste, smell, sight, hearing).

- Expulsion/Emanation (Samudghāta): Seven types of emanation from the soul's particles (pain, passion, death, Vaikriya, Taijasa, Āhārika, Kevali).

- Vision/Perspective (Drishti): Three types of vision (false, right, mixed).

- Perception/Knowledge (Darshana): Four types of perception (ocular, non-ocular, clairvoyant, omniscient).

- Knowledge (Jnana): Five types of knowledge (sense-based, scriptural, clairvoyant, mind-reading, omniscient).

- Ignorance (Ajñāna): Three types of ignorance (wrong sense-based, wrong scriptural, illusory knowledge).

- Yoga (Activities/Karma-inducing actions): Types of mental, verbal, and physical activities.

- Usage/Application (Upayoga): Aspects of soul's energy (manifested/conscious and unmanifested/unconscious).

- Generation/Birth (Utpāda): Number of souls born at a given moment.

- Cessation/Death (Vyavata): Number of souls ceasing to exist at a given moment.

- Duration of Life (Sthiti): Minimum and maximum lifespan for different beings.

- Perfection/Maturity (Paryapti): Stages of development in acquiring sustenance, body, senses, breath, speech, and mind.

- Nourishment/Ingestion (Āhāra): How beings acquire sustenance.

- Consciousness Categories (Sanjna): Reiteration of forms of consciousness.

- Movement/Destination (Gati): Where beings go after death.

- Arrival/Origin (Agati): From where beings are born.

- Gender/Attraction (Veda): Predominant sensual inclination (feminine, masculine, neuter).

- Quantity/Numbers (Alpabahutva): Relative abundance of beings in different dandakas.

-

Detailed Analysis within Dandakas: For each of the 25 aspects, the text explains how it applies to each of the 24 dandakas, noting similarities, differences, and exceptions. For instance, it details which types of bodies are present in each dandaka, the specific types of leshya applicable, the lifespan ranges, and the types of knowledge and consciousness possessed.

-

Author's Personal Reflection and Prayer (Pages 77-78):

- The author reflects on their own repeated births and deaths across the various dandakas and expresses the suffering associated with this cycle.

- They offer a prayer to the Jinas (Tirthankaras) for liberation from this cycle of birth and death, seeking the ultimate state of salvation (Moksha) which is attained through the cessation of mental, verbal, and physical actions (dandaka).

-

Authorship and Colophon (Pages 78-79):

- The text concludes with the author's name, Muni Gajasar, who was a disciple of Upadhyay Shridhavalchandra, under the guidance of Acharya Jinahansuri.

- The work is presented as a "Vijnapti" (supplication or exposition) for the spiritual benefit of the author and others.

- A note from 1578 VS (1521 AD) in Patan, by the authors of the commentary, requests intelligent readers to correct any childlike errors.

Overall Significance:

"Dandakvichar" is a foundational text in Jainism for understanding the classification of souls and the intricate details of their existence across different realms. It serves as a guide for spiritual practitioners by illustrating the consequences of karma and the path to liberation. The inclusion of the biography of Bai Parvatibai and the publisher's notes highlights the text's connection to a specific Jain community and its efforts in propagating Jain teachings. The work systematically categorizes souls based on their physical form, lifespan, sensory capabilities, mental states, and migratory patterns, providing a comprehensive framework for spiritual study.