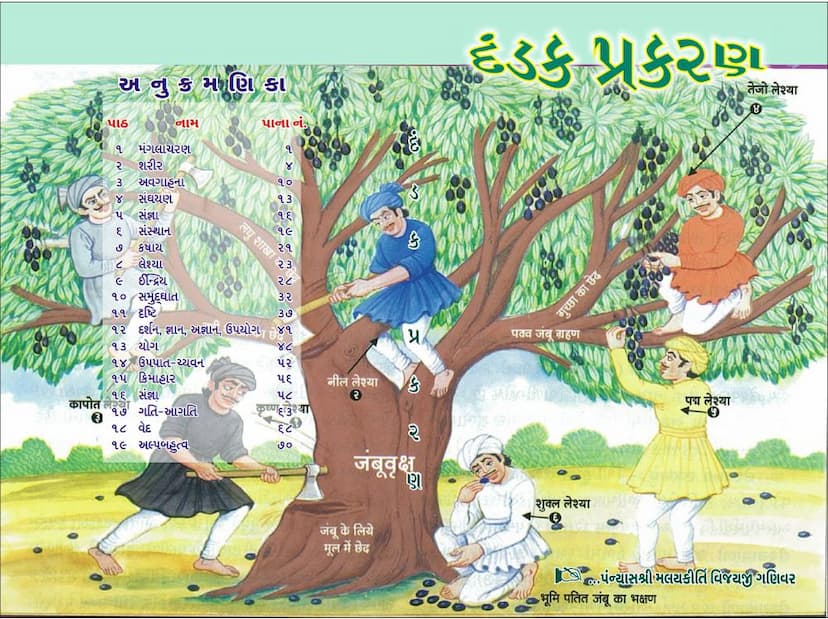

Dandak Prakaran

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Dandak Prakaran" by Malaykirtivijayji, based on the provided pages:

Overview and Purpose of the Book:

The "Dandak Prakaran" is a Jain scripture authored by Malaykirtivijayji, published by Malaykirtivijayji. Its primary aim is to explain the "Dandak" or categories of living beings in Jainism, providing detailed information about their characteristics. The book uses the framework of "Dandak Padas" (terms related to the categories) and "Dwaras" (aspects or characteristics) to systematically analyze these beings. The author begins with a mangalacharan (auspicious invocation) and outlines the scope of the text, which is to present the essence of Jain scriptures in a concise manner.

Key Concepts and Structure:

The text is structured into chapters, each focusing on a specific aspect of living beings, termed as "Dwaras." The introductory pages and the early chapters clearly define the foundational concepts:

- Dandak: Living beings who are "punished" or subjected to suffering due to karma. The text identifies 24 "Dandak Padas" that encompass all classifications of souls, starting from one-sensed beings (like earth-bodied) up to omniscient beings (Vaimaniks).

- Dwaras: These are the 24 aspects or characteristics through which each "Dandak" is analyzed. These include: Body (Sharir), Length/Height (Avagahana), Bone Structure (Sanghayana), Instincts/Sensibilities (Sanjna), Body Shape (Sansthan), Passions (Kashaya), Aura/Coloration (Leshya), Sense Organs (Indriya), Ejection/Expulsion (Samudghat), Vision/Perspective (Drishti), Perception (Darshan), Knowledge (Gyan), Ignorance (Agyan), Psychical Activities (Yoga), Conscious Activity (Upayoga), Rebirth (Upapat), Death/Cessation (Chyavan), Lifespan (Sthiti), Maturation (Paryapti), Food Intake (Kimahar), Sentience (Sannin), Movement (Gati), Return Movement (Agati), and Sensations/Feelings (Veda).

- Mangalacharan: The text begins with a salutation to the 24 Tirthankaras, establishing auspiciousness and the authority of the teachings.

- Purpose and Audience: The book aims to provide knowledge, facilitate self-study (swadhyaya), foster devotion to Jain principles, and ultimately guide the reader towards spiritual liberation (moksha). The intended audience is "bhavya jivas" (auspicious souls) who possess curiosity and faith.

Summary of Key Chapters/Dwaras Covered:

-

Mangalacharan (Chapter 1): Sets the tone with an invocation, defines the scope of the text (Dandak Padas and Dwaras), and outlines the author's purpose and the reader's qualifications. It clarifies what "Dandak" means and lists the 24 Dandak Padas, also enumerating the 24 Dwaras.

-

Sharir (Body) (Chapter 2): Discusses the concept of "Varganas" – categories of subtle matter that souls can absorb to form their bodies. It details the eight Varganas: Audarik, Vaikriya, Aharak, Taijasa, Bhasha, Shwasochchwas, Mana, and Karmana. It then elaborates on the five types of bodies (Audarik, Vaikriya, Aharak, Taijasa, and Karmana), describing their nature, who possesses them, and their significance.

- Audarik Body: Possessed by all humans and animals; considered great for its association with discipline and liberation.

- Vaikriya Body: Possessed by gods and hell-beings; allows for transformations in form and size.

- Aharak Body: Used by advanced ascetics for spiritual investigation; invisible to the naked eye.

- Taijasa Body: Associated with internal heat and digestion; enables the manifestation of Tejo and Sheet Leshyas.

- Karmana Body: The subtle body that accompanies the soul throughout its transmigration, carrying karmic impressions.

-

Avagahana (Length/Height) (Chapter 3): Explains Avagahana as the space occupied by a body. It details the varying lengths and heights of different bodies and beings across various categories (Dandaks) and lifespan stages, from the immeasurable length of subtle bodies to the specific dimensions of gross bodies. It also explains the concept of initial contraction of the soul at the time of rebirth.

-

Sanghayana (Bone Structure) (Chapter 4): Describes the six types of bone structures in living beings, from the strongest (Vajra Rishabhanaracha) to the weakest (Shevatam). It explains that gods, hell-beings, and one-sensed beings do not have this structure. The text details which beings possess which Sanghayana and the immense strength associated with the higher types, emphasizing that only those with the first Sanghayana can attain omniscience.

-

Sanjna (Instincts/Sensibilities) (Chapter 5): Defines Sanjna as the indicator of life in a being. It categorizes Sanjnas into two main types: Jnana Sanjna (related to types of knowledge) and Anubhava Sanjna (related to experiences). Anubhava Sanjna is further broken down into 4, 6, 10, or 16 types, including instincts for food, fear, sex, possession, anger, pride, deceit, greed, etc. It explains the karmic origins of these instincts and highlights the negative impact of succumbing to them, advocating for their conquest through spiritual practice.

-

Sansthan (Body Shape) (Chapter 6): Describes the six types of body shapes, from perfectly symmetrical (Samachaturasra) to grotesque (Hundak). It explains which beings possess which shapes and how geographical location (Kshetras) influences the prevalent body shapes. It notes that certain body shapes are prerequisites for spiritual advancement.

-

Kashaya (Passions) (Chapter 7): Defines the four primary passions: Anger (Krodha), Pride (Mana), Deceit (Maya), and Greed (Lobha). It details their destructive nature, how they lead to suffering in this life and the next, and provides examples of how attachment to these passions has led to unfortunate rebirths. The text advises cultivating virtues like forgiveness, humility, honesty, and contentment to overcome these passions.

-

Leshya (Aura/Coloration) (Chapter 8): Explains Leshya as the state of the soul's consciousness, manifesting in six colors: Krishna (black), Neela (blue), Kapota (dove-colored), Tejo (fiery), Padma (lotus-colored), and Shukla (white). The first three are considered inauspicious, and the latter three auspicious. The text uses vivid examples to illustrate the nature of each Leshya and its impact on one's spiritual journey. It distinguishes between Dravy Lleshya (gross form) and Bhav Lleshya (inner state) and explains how they can change and their correlation with spiritual stages (Gun Sthan).

-

Indriya (Sense Organs) (Chapter 9): Details the five types of sense organs: touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing. It explains the concept of external (Bahya Nivrutti), internal (Antar Nivrutti), and functional (Upakaran) aspects of sense organs, as well as the soul's inherent capacity (Labdhi Bhavendriya) and its use (Upayoga Bhavendriya). It clarifies the 24 different aspects of sense organs and the role of karma in their development and function. It also explains why the mind is considered a "non-sense organ."

-

Samudghat (Ejection/Expulsion) (Chapter 10): Describes seven types of Samudghat – processes where a soul's particles extend outside the body to interact with karmas. These include Vedana (pain), Kashaya (passions), Maran (death), Vaikriya (body transformation), Taijasa (fiery body activity), Aharak (subtle body activity), and Kevali (omniscient being's cosmic activity). The text details the purpose and nature of each Samudghat and which types of beings can experience them.

-

Drishti (Vision/Perspective) (Chapter 11): Categorizes perspective into three types: Mithya Drishti (wrong view), Samyag Drishti (right view), and Mishra Drishti (mixed view). It emphasizes that Tirthankaras, being omniscient and free from passion, never lie. It explains that accepting Tirthankara's teachings with faith is the hallmark of Samyag Drishti, while rejecting them leads to Mithya Drishti. The text highlights the importance of faith for spiritual progress.

-

Darshan, Gyan, Agyan, Upayoga (Perception, Knowledge, Ignorance, Conscious Activity) (Chapter 12): Distinguishes between Darshan (perception of general qualities) and Gyan (knowledge of specific qualities). It explains that while both are always present as potential (Labdhi), only one can be actively used at a time (Upayoga). It describes the five types of knowledge (Mati, Shrut, Avadhi, Manahparyav, Keval) and the three types of ignorance (Mati Agyan, Shrut Agyan, Vibhang Gyan), as well as the four types of perception and their respective uses. It also explains how karmic obscurations affect the clarity of knowledge and perception.

-

Yoga (Psychical Activities) (Chapter 13): Explains Yoga as the activities of the soul, categorized into three main types: Mano Yoga (mental activity), Vachan Yoga (verbal activity), and Kaya Yoga (physical activity). It details the sub-categories of each, such as true/false mental and verbal expressions, and the various types of physical activities related to different bodies (Audarik, Vaikriya, etc.). It outlines which beings have which types of Yoga.

-

Upapat - Chyavan (Rebirth - Death) (Chapter 14): Discusses the processes of birth (Upapat) and death (Chyavan) for different categories of beings. It provides information on the number of beings born and dying simultaneously and the periods of interruption (Virahakal) for these events across various life forms.

-

Kimahar (Food Intake) (Chapter 15): Explains "Kimahar" in the context of how souls absorb subtle matter from different directions (six cardinal directions) based on their location in the universe and whether they are touched by the non-space (Aloka). Souls in the outer regions of the universe might have restricted access to matter from certain directions.

-

Sanjna (Instincts/Sensibilities) (Chapter 16): Revisits the concept of Sanjna, this time categorizing beings as "Sanjni" (with mind or advanced sensibilities) and "Asanjni" (without mind or basic sensibilities). It describes three types of Sanjna: Hetuvadopadeshiki (present-minded), Dirghakaliki (past, present, and future-minded, enabled by the mind), and Drishtivadopadeshiki (possessing right perception and knowledge). It clarifies that beings without a mind are Asanjni, while those with a mind are Sanjni.

-

Gati-Agati (Movement and Return Movement) (Chapter 17): Details the principles of transmigration, explaining which types of beings can be reborn into which categories (Gati) and from which categories they can originate (Agati). It illustrates the complex web of rebirths, highlighting restrictions such as beings from certain realms not being able to be reborn into others, and the influence of physical attributes like Sanghayana on the potential destinations.

-

Veda (Sensations/Feelings) (Chapter 18): Discusses the three types of Vedas: Purusha Veda (masculine feeling), Stri Veda (feminine feeling), and Napunsak Veda (neuter feeling). It explains how these are related to the soul's attraction towards males, females, or both, driven by the "Veda Mohaniya" karmas. It also outlines which categories of beings experience which type of Veda.

-

Alpabahutva (Quantity Comparison) (Chapter 19): This section focuses on comparing the numerical quantities of different types of beings. It explains terms like "Visheshadhik" (slightly more), "Sankhyat Gun" (times the number), "Asankhyat Gun" (infinitely more), and "Anant Gun" (infinitely more) to quantify populations of beings. It provides a hierarchical comparison of the populations of various life forms, from humans to elemental beings.

Overall Significance:

"Dandak Prakaran" serves as a foundational text for understanding the diverse classifications of living beings in Jainism. It meticulously details their physical characteristics, karmic predispositions, and spiritual potentials. By systematically analyzing each category through the lens of the 24 Dwaras, the book aims to provide a comprehensive and structured understanding of the Jain cosmology and the journey of the soul through the cycle of birth and death, ultimately guiding the reader towards the path of liberation.