Charupnu Avalokan

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This Jain text, "Charupnu Avalokan" (Observation of Charup), authored by Mangalchand Lalluchand and Chunilal Maganlal Zaveri, and published by Mangalchand Lalluchand, appears to be a detailed account of a significant legal and social dispute concerning a Jain temple in the village of Charup, Gujarat.

Here's a summary based on the provided pages:

Title and Authorship:

- Book Title: Charupnu Avalokan (ચારૂપનું અવલોકન) - Meaning "Observation of Charup."

- Author(s): Mangalchand Lalluchand and Chunilal Maganlal Zaveri.

- Publisher: Mangalchand Lalluchand.

- Publication Year: 1975 (corresponding to Samvat 1975, as mentioned on page 3).

The Core Issue: A Temple Dispute in Charup

The text primarily focuses on a conflict that arose at the Jain temple of Shri Shamalaji Parshwanath in Charup village. This conflict was triggered by the presence of idols of Hindu deities (Mahadev, Ganpati, Parvati, etc.) within the Jain temple premises, which led to religious disputes between the Jain community and the Smarta community (followers of Hinduism).

Historical Context of Charup and its Temple:

- Ancient Tirth: Charup is described as an ancient and significant Jain pilgrimage site, located a few kilometers from Anhilpur Patan, the ancient capital of Gujarat.

- Past Prosperity: In ancient times, it was a prosperous location, possibly inhabited by Jains, as evidenced by archaeological findings like hidden remnants of past Jain settlements.

- Current Demographics: Currently, the village has a population of only about 100-150 households, primarily consisting of farmers, and notably, no Jain households.

- The Temple: Despite the lack of a Jain population, the village houses a Jain temple dedicated to Shri Shamalaji Parshwanath. The text suggests that the ruins of a prosperous Jain settlement lie hidden underground.

- Temple Administration: The temple's administration is currently managed by the Jain Sangh of Patan.

The Incident and Escalation:

- Presence of Non-Jain Idols: It's mentioned that within the Shri Shamalaji Parshwanath temple, there were also idols of Hindu deities like Mahadev, Ganpati, and Parvati.

- Removal of Idols: The Jain community apparently removed these Hindu idols.

- Reaction from the Smarta Community: The Smarta community felt their religious sentiments were hurt by the removal of the idols.

- Counter-Action by Smartas: In response, the Smarta community performed Havan (fire ritual) within the Shamalaji temple, which in turn hurt the sentiments of the Jain community.

- Legal Battles Ensued: This led to a series of legal cases in the courts of Patan and Mehsana, involving charges and counter-charges. The text details multiple court proceedings, appeals, and judgments, highlighting financial expenses and the escalation of animosity between the communities.

The Arbitration Process:

Recognizing the fut1le nature of the ongoing legal battles and the escalating conflict, both communities agreed to resolve the dispute through arbitration.

- Multiple Attempts: Several attempts were made to find a neutral arbitrator, including proposals involving Ahmedabad-based Jains and Smartas, and even invoking the Shankracharya. However, these attempts failed due to disagreements on the arbitration panel.

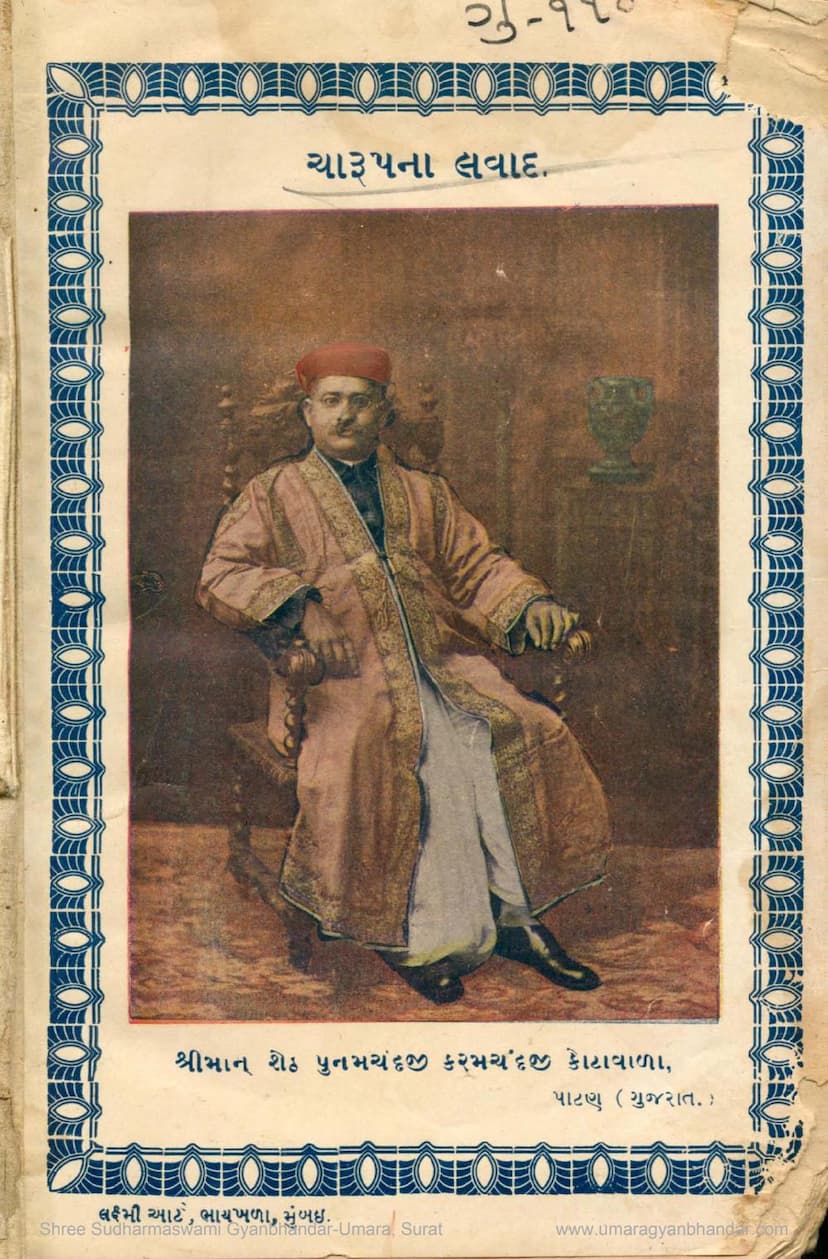

- Appointment of Seth Punamchand Karamchand Kotaawala: Ultimately, both sides agreed to appoint Seth Punamchand Karamchand Kotaawala, a respected Jain businessman from Patan (and residing in Mumbai), as the sole arbitrator. He was chosen due to his reputation for impartiality and integrity.

- The Award: Seth Kotaawala, after hearing both sides and considering the situation, delivered an award (on January 21, 1917, corresponding to Paush Vad 13, Samvat 1973). The award involved the Smarta community being given possession of a part of the temple complex (two rooms from the dharamshala and adjacent land) and a sum of ₹2000/- for the re-establishment and worship of their deities. The award also included stipulations regarding the placement of new temple structures and the conduct of rituals.

Reactions and Counter-Reactions to the Award:

- Initial Acceptance: The award was initially read out publicly and met with appreciation from both sides.

- Subsequent Opposition: However, a section of the Jain community, particularly those associated with the Patan Jain Sangh and influenced by certain publications and opinions (including those from Jain monks), began to oppose the award. They felt the arbitrator's commentary was detrimental to Jain principles and could harm future Jain religious sites.

- Publication of Opinions: This opposition led to the printing and distribution of handbills and articles in newspapers, questioning the award and seeking opinions from other monks and influential individuals.

- Newspaper Debates: The dispute became a subject of public debate in various newspapers like "Jain," "Jain Shasan," and "Hindustan," with strong opinions presented from both sides. Some newspapers praised the award for its wisdom and fairness in resolving a complex issue, while others criticized it, accusing the arbitrator of partiality or misunderstanding Jain principles.

- Legal Scrutiny of the Award: The text also mentions a legal opinion obtained from a Barrister regarding the award, suggesting that while the financial and property aspects were binding, the arbitrator's commentary might be considered personal opinion rather than legally binding religious doctrine.

- Failed Attempt to Invalidate the Award: There was an attempt to obtain support for invalidating the award, including the idea of transferring the idol of Shamalaji Parshvanath from Charup to Patan. This attempt was met with criticism from some quarters, including the "Jain Shasan" newspaper.

The Underlying Issues and Interpretations:

- Preservation of Jain Identity: The core of the opposition seemed to stem from the fear that the award's wording, particularly regarding the presence and accommodation of Hindu deities, might compromise Jain principles, historical claims, and the sanctity of Jain temples.

- The Role of Munis and Community Leaders: The text highlights the influence of Jain monks and community leaders in shaping public opinion regarding the award, with some supporting it and others actively campaigning against it.

- The Importance of Arbitration: Despite the controversy, the initial agreement to arbitration was seen as a positive step towards resolving disputes peacefully, avoiding further costly legal battles, and fostering harmony between communities.

- The Authors' Stance: The authors of the book seem to generally support the award, emphasizing the arbitrator's wisdom, fairness, and the beneficial outcome of resolving the conflict. They highlight the efforts made by Seth Kotaawala to achieve peace and preserve the sanctity of the pilgrimage site.

Conclusion:

The book "Charupnu Avalokan" appears to be a thorough documentation of a complex dispute, the arbitration process, the subsequent reactions, and the broader context of inter-religious relations and community leadership within the Jain tradition of that era. It reveals a vibrant, yet sometimes contentious, social and religious landscape in Gujarat. The extensive inclusion of newspaper articles, legal documents, and opinions suggests the authors' intent to provide a comprehensive and perhaps definitive account of the Charup case and the efforts to resolve it.