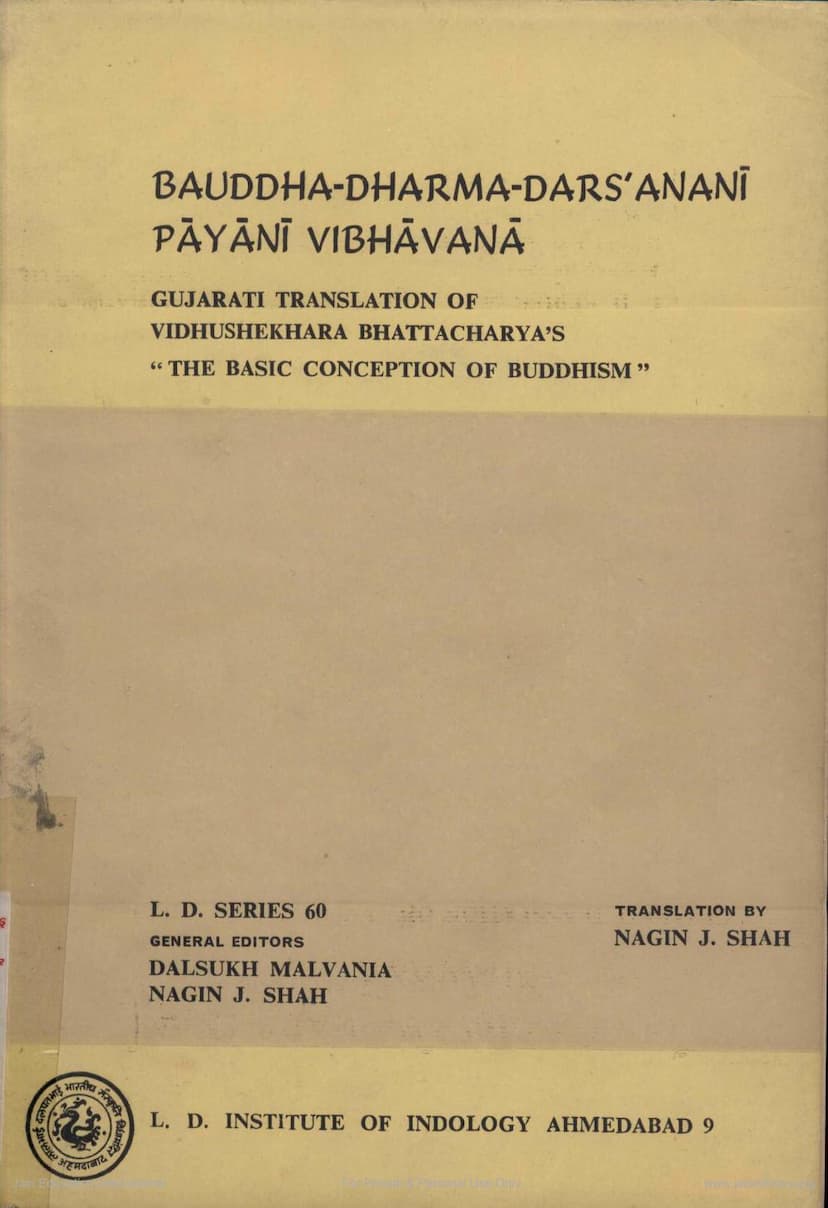

Buddha Dharma Darsanani Payani Vibhavana

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This book, titled "Baudha-Dharma-Dars'anani Payani Vibhavana" (The Basic Conception of Buddhism), is a Gujarati translation of Vidhushekhar Bhattacharya's "The Basic Conception of Buddhism." Published by L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, in May 1977, it aims to present the fundamental principles of Buddhism to Gujarati readers who may not be proficient in English.

The book is divided into two lectures:

First Lecture: Introduction

- Pre-Buddha Religious and Philosophical Landscape: The lecture begins by outlining the religious and philosophical milieu in India before the advent of the Buddha. It highlights the Vedic ritualists (Karmis, Yajnikas) who focused on performing sacrifices for worldly and otherworldly pleasures and immortality. They believed in the power of rituals and the existence of an immortal soul that experiences the fruits of karma.

- The Rise of the Vedantins: A significant shift occurred with the emergence of a new school of thinkers, primarily the Vedantins. They lost faith in Vedic rituals, deeming them insufficient for liberation. They believed that true liberation comes from an uncreated, eternal, and inherent self – the Atman. They emphasized the Atman as the dearest entity, the bridge to immortality, and the key to overcoming suffering. Their goal was to realize the Atman, which they considered the source and dissolution of the universe. They also believed that knowledge and the cessation of desires (Kama) were essential for liberation.

- The Interplay of Ritualism and Knowledge: The text notes the existence of a middle path that sought to reconcile ritualism and the path of knowledge, suggesting the necessity of both for achieving the ultimate goal. The importance of Yoga and knowledge of subtle nervous systems is also mentioned.

- The Challenge to Vedic Authority: The authority of the Vedas, once paramount, began to loosen. The Sankhya philosophy emerged, rejecting Vedic rituals due to animal sacrifice and emphasizing knowledge and a transformed concept of the Atman, while also dispensing with the idea of a creator God.

- Emergence of Diverse Philosophies and Asceticism: This period saw a proliferation of thinkers and spiritual leaders who claimed to have found paths to liberation independently of the Vedic tradition. This led to numerous sects with varying views on the nature of the universe and the soul (eternal, non-eternal, or a combination), the origin of the world, the existence of the soul after death, and the role of knowledge versus action. Ascetics also practiced various forms of penance and self-mortification to conquer the senses.

- The Advent of Buddha and Mahavira: Against this backdrop of intellectual ferment, Gautama Buddha and Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism) appeared.

- Buddha's Rationalism and Pragmatism: The author emphasizes Buddha's profound rationalism, attributing it to the circumstances of his birth. Buddha did not accept traditions blindly but based his beliefs on strong reasoning. He encouraged his followers to test his teachings rather than accept them out of reverence. His pragmatism is highlighted by his refusal to engage in discussions that did not lead to the goal, often preferring silence on abstract philosophical questions.

- The Unanswered Questions and Buddha's Silence: The text discusses the "fourteen unanswered questions" (avyakrtani) that Buddha often evaded, such as the eternality of the world, the finiteness of space, the nature of the Tathagata after death, etc. He likened the insistence on these questions to a person dying from a poisoned arrow before knowing the details of the archer or the arrow. Buddha's silence was partly due to the inability of listeners to comprehend the subtle truth, and partly because his Middle Path did not allow for simple "yes" or "no" answers, which would lean towards eternalism or nihilism.

- The Four Noble Truths: The core of Buddha's teachings, delivered after his enlightenment, is presented as the explanation of the "four basic truths": Suffering (Dukkha), the cause of suffering (Dukkha-hetu), the cessation of suffering (Dukkha-hana), and the path to the cessation of suffering (Dukkha-hanopaya). These are compared to the four truths of Ayurveda: disease, cause of disease, health, and medicine.

- The Diverse Nature of Buddhist Teachings and Texts: The author notes the vastness and diversity of Buddhist literature and the challenges in understanding the true meaning of Buddha's teachings due to variations in languages of origin (Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhramsha, Paishachi) and the potential for lost or added material in existing texts. The rise of different "Yanas" (vehicles) like Hinayana, Mahayana, etc., is attributed to the differing interpretations of Buddha's disciples.

- The Role of Upaya-Kaushalya (Skillful Means): The concept of skillful means is introduced to explain the apparent contradictions in Buddha's teachings. Just as a physician treats patients differently, Buddha adapted his teachings to the varying capacities and inclinations of his audience. While various Yanas exist, the ultimate goal and the underlying truth remain one.

- The Importance of Sandha-Bhasha (Meaning-Speech): The text explains the concept of "Sandha-Bhasha" or "meaning-speech," where words have both an exoteric (lokabhogya) and an esoteric (guhya, adhyatmika) meaning. This concept, present even in Upanishadic literature, is seen as a significant factor in the later development of Tantric Buddhism and potentially contributes to misunderstandings of the original teachings.

- The Problem of "Nita-artha" and "Neya-artha": The distinction between "Nita-artha" (understood meaning, definitive) and "Neya-artha" (to be understood meaning, requiring interpretation) sutras is discussed, emphasizing the need to follow the former.

- The Core Message: The Eightfold Path: The Buddha's primary discourse focused on the four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path as the means to overcome suffering, which he identified with "Kama" (desire/craving), synonymous with "Mara" (death).

Second Lecture: The Fundamental Problem

- Reiteration of the Difficulty in Interpretation: The lecture begins by restating the challenge of understanding Buddha's teachings due to the diversity and contradictions in the Buddhist canon and the interpretations of his followers.

- The Buddha's Debt to Predecessors: The author emphasizes that Buddha's teachings were shaped by the existing philosophical and religious currents, particularly the emphasis on the cessation of desire (Kama) as the root of suffering.

- Buddha's Interpretation of Karma: While his predecessors understood "karma" primarily as ritualistic acts, Buddha redefined it as mental, verbal, and physical actions, with the ultimate essence being consciousness or mental karma. He declared, "I call consciousness karma."

- The Centrality of Desire (Kama) and Ignorance (Avidya): The book highlights the common understanding among Buddha and his predecessors that desire (Kama) is the root of suffering. However, Buddha identified ignorance (Avidya) as the ultimate root cause, from which desire arises. Ignorance is defined as a lack of or distorted understanding of reality.

- The Concept of Atman vs. Anatman: While Upanishadic sages advocated for the realization of the Atman (Self) as the path to liberation and bliss, Buddha rejected the concept of a permanent, inherent Self (Atman). He taught the doctrine of Anatman (no-self).

- The Upanishadic Atman and Buddha's Reinterpretation: Buddha acknowledged the Upanishadic understanding of Atman as the ultimate object of attachment, which fuels desire. However, he found that the Atman, as described by the Upanishads (eternal, blissful, independent), could not be located. He analyzed the five aggregates (skandhas: form, feeling, perception, mental formations, consciousness) and concluded that none of them, nor any combination thereof, could be identified as the Atman.

- The Rejection of Atman and its Consequences: By denying the existence of a permanent Atman, Buddha aimed to dismantle the very foundation of attachment and desire. This led to the concepts of impermanence (Anitya) and non-self (Anatman).

- The Doctrine of Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination): To explain the continuity of existence without a permanent soul, Buddha introduced the concept of Pratītyasamutpāda. This doctrine states that all phenomena arise in dependence on causes and conditions. This interconnectedness explains the causal chain of existence without positing an independent self.

- The Two Components of Existence: Nama and Rupa: The "so-called" life is explained as a combination of "Nama" (mind, consciousness, mental factors) and "Rupa" (form, matter, physical phenomena). Both are impermanent and arise in dependence on causes and conditions, operating according to Pratītyasamutpāda.

- The Problem of Continuity and the Buddhist Solution: The apparent contradiction between impermanence and the continuity of experience (memory, recognition) is addressed by the concept of a continuous stream of consciousness and conditioned existence, rather than a migrating soul. The analogy of a flame passing from one lamp to another illustrates this point.

- The Goal: Cessation of Desire and Nirvana: By dismantling the notions of Atman and selfhood, Buddha aimed to eradicate desire (Kama), which he saw as the root of all suffering. The ultimate goal is Nirvana, the cessation of suffering and the cycle of rebirth.

In essence, the book meticulously traces the philosophical lineage that influenced Buddha, highlights his unique contribution of Anatman and Pratītyasamutpāda, and explains the complexities and challenges in understanding his core teachings due to the diverse interpretations and the use of skillful means. The central problem addressed is how to achieve liberation from suffering by understanding the fundamental nature of reality as taught by the Buddha, with a particular focus on the eradication of desire and ignorance through the realization of no-self.