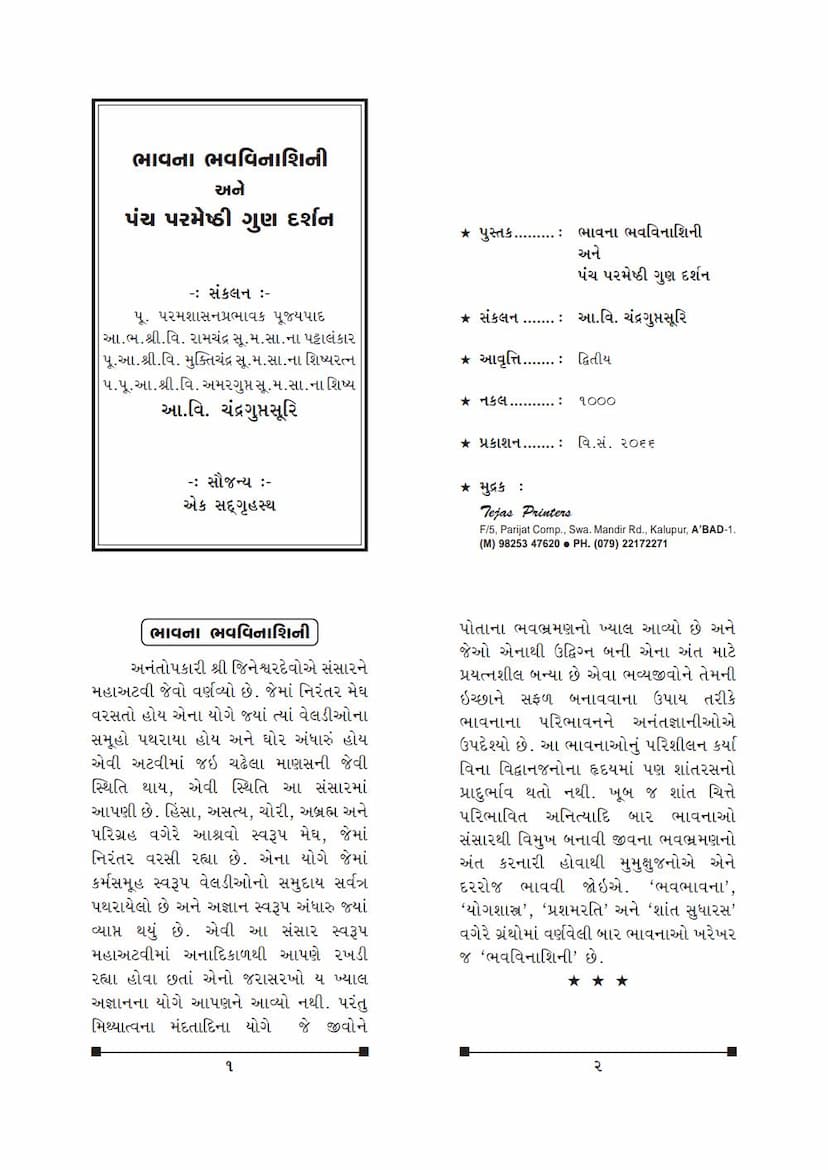

Bhavna Bhav Vinashini Ane Panch Parmeshthi Gun Darshan

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

The Jain text "Bhavna Bhav Vinashini ane Panch Parmeshthi Gun Darshan" (Meaning: Bhavanas that Destroy Birth Cycles and the Vision of the Virtues of the Five Supreme Beings), authored by Acharya Shri Chandraguptasuri, is a spiritual guide that focuses on the profound contemplation of specific mental states, known as Bhavanas, for spiritual liberation, and then elaborates on the virtues of the Five Supreme Beings of Jainism.

Part 1: Bhavna Bhav Vinashini (Bhavanas that Destroy Birth Cycles)

This section details a series of Bhavanas, or profound contemplations, that are considered essential for detaching oneself from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). The author emphasizes that these Bhavanas are taught by omniscient beings (Jineshwar Devos) as a means to overcome ignorance and suffering. The text describes these Bhavanas as "Bhav-Vinashini" (destroyers of birth cycles).

The following Bhavanas are explained:

-

Anitya Bhavana (Contemplation of Impermanence): This Bhavana highlights the transient nature of all worldly possessions, relationships, health, youth, and even the body itself. It states that nothing in the universe is eternal and that all things undergo constant change. Experiencing these worldly pleasures leads to further sinful actions and subsequent suffering. The contemplation of impermanence helps detach from fleeting pleasures and focus on self-welfare, like Hanumanji.

-

Asharan Bhavana (Contemplation of Helplessness): This Bhavana emphasizes that in the face of birth, old age, disease, and death, there is no refuge in the world except the teachings of the omniscient Jinas. Even powerful rulers, celestial beings, and great warriors are rendered helpless at the time of death. The text criticizes the living for not seeking refuge in the teachings of the Arihant or their spiritual guides, despite experiencing this helplessness. It suggests that dedicating efforts to the path of religion, which eliminates death permanently, would lead to an eternal, deathless state, similar to that achieved by great monks.

-

Sansar Bhavana (Contemplation of the Worldly Cycle): The text describes the world (samsara) as painful, the abode of pain, and the cause of suffering. It details the suffering experienced in the lower realms (hell and animal kingdoms) and even in the human realm, which includes worries about livelihood, wealth, family, diseases, and dependence on others. The cycle of desire leads to constant anxiety and dissatisfaction. Even celestial beings experience jealousy and the fear of losing their enjoyments. Contemplating the true nature of this suffering-filled world leads to detachment from worldly pleasures.

-

Ekatva Bhavana (Contemplation of Oneness/Solitude): This Bhavana addresses the suffering caused by attachment (mamta) in the cycle of existence. The soul's true nature is pure knowledge, but karmic influence binds it. When one reflects deeply, it becomes clear that no one truly belongs to anyone else in this world. What we accumulate is not truly ours. We enter the world empty-handed and leave it the same way. Even loved ones will not share our suffering. The text highlights that developing the Bhavana of "no one is mine, and I belong to no one" without dejection can lead to liberation, as exemplified by Mata Marudevidevi and Ganadhar Gautamswami.

-

Anyatva Bhavana (Contemplation of Otherness/Difference): This Bhavana distinguishes between the soul (jiva) and non-soul (ajiva). Despite being one in essence, their qualities are distinct. Karmic matter has merged with the soul, causing it to forget its true nature. The soul, being pure consciousness, has no relation to inert physical substances like the body. Clinging to these material possessions and the body leads to undeserved suffering. The text states that the body and other physical objects are destroyed, while the soul is eternal. By recognizing the body and other possessions as different from the soul and striving to overcome attachment to them, one can realize their pure nature.

-

Ashuchi Bhavana (Contemplation of Impurity): The soul, endowed with infinite knowledge and perception, is as pure as a crystal. However, residing in the impure body, the soul forgets its pure state due to attachment to the body. The text elaborates on the inherent impurity, foul smell, and repulsive nature of the body, despite attempts to cleanse and adorn it. It states that the body has a nature to make even pure substances impure. Those who see the body as beautiful are blinded by delusion. Contemplating the impurity of the body helps in overcoming attachment to it and achieving self-welfare, as did King Sanatkumar and others.

-

Ashrav Bhavana (Contemplation of Influx of Karma): This Bhavana explains karma as the sole cause of the soul's impurity. Ashrav refers to the channels through which karmic matter enters the soul. The four primary Ashravas are Mithyatva (false belief), Avirati (non-restraint), Kashaaya (passions), and Yoga (activities of mind, speech, and body). The text details 42 types of Ashravas, including the five senses, four passions, violence, falsehood, theft, etc. It highlights Mithyatva and Avirati as particularly detrimental, as they prevent the attainment of the threefold jewels (right faith, right knowledge, right conduct) necessary for liberation. It emphasizes the importance of controlling Ashravas to achieve freedom from suffering.

-

Samvar Bhavana (Contemplation of Cessation of Karma): This Bhavana describes the process of stopping the influx of karma (Ashrav). Samvar prevents new karmic bondage. It is essential for achieving a state of karmalessness. The text lists 57 means of Samvar, including five Samitis (carefulness in conduct), three Guptis (restraint of mind, speech, and body), 22 Parishahas (endurance of hardships), ten types of asceticism, twelve Bhavanas, and five types of conduct. It states that by practicing these means, one can gradually reach the state of Shaileshi (complete cessation of karma).

-

Nirjara Bhavana (Contemplation of Shedding Karma): This Bhavana defines Nirjara as the separation from accumulated karma. It is achieved through penance (tapa), which has twelve types. These are divided into six external austerities (Anashan, Unodari, Vritti Sankshipt, Ras Tyag, Kayaklesh, Sanlinata) and six internal austerities (Prayashchit, Vinay, Vaiyavachch, Swadhyaya, Dhyan, Kayotsarg). The text elaborates on each of these, explaining their significance in shedding karma and achieving liberation.

-

Bodhi Durlabh Bhavana (Contemplation of the Rarity of Enlightenment): This Bhavana stresses the extreme rarity of attaining right faith (Samyak Darshan), which is the prerequisite for right knowledge and right conduct. While human birth, favorable circumstances, and heavenly enjoyments are obtained through past merits, the acquisition of true enlightenment is exceedingly difficult. The text states that even for those with a limited remaining lifespan in samsara, true enlightenment can be attained through pure resolve. Even a brief moment of right faith can lead to liberation within a specific period. This Bhavana also serves to avert rebirth in lower realms and reduce suffering in the present life. The text also mentions that in some texts, this Bhavana is referred to as "Dharma Bhavana," focusing on the excellence and influence of Dharma.

-

Lok Swaroop Bhavana (Contemplation of the Nature of the Universe): This Bhavana describes the universe as the foundation of five substances: Dharma, Adharma, Jiva, Pudgal, and Kala. The universe is vast, and in its 14 realms, souls have taken various forms due to karma. The universe is seen as a stage for the soul to play out its karmic roles. The text states that the soul has experienced birth and death countless times in every region of the universe. Despite experiencing joy and sorrow based on favorable or unfavorable circumstances, the soul remains trapped in this cycle. Contemplating the true nature of these circumstances and the acquisition of karmic matter as the result of past actions can inspire a desire to overcome karma and attain eternal residence at the apex of the universe (Moksha).

-

Dharma Swakhyat Bhavana (Contemplation of Rightly Taught Religion): This Bhavana, as described by Acharya Umaswati, emphasizes that religion, taught by the Jinas who have conquered inner enemies like attachment, is the means for the well-being of all beings. Those who adhere to this path can easily cross the ocean of samsara. The text distinguishes true religion from false imitations, stating that any path that does not benefit beings, in the present or future, is not true religion. It highlights the importance of following the teachings of the Arihants and their sincere expounders.

-

Maitri Bhavana (Contemplation of Friendship/Benevolence): This Bhavana, along with Pramod, Karuna, and Madhyastha, is taught for stabilizing religious meditation. Maitri Bhavana is the desire that no living being commits sin or suffers. It is understood that sin is the cause of suffering, and to end suffering, one must end sin. The ultimate goal of this Bhavana is for all beings to be liberated from the cycle of samsara. It is impossible to have genuine compassion for others without a sincere desire for one's own welfare and liberation.

-

Pramod Bhavana (Contemplation of Joy/Appreciation): As described in the "Yogashastra," Pramod Bhavana is the appreciation for the virtues of wise beings who are free from all faults and see the true nature of reality. It is not easy to feel joy from the qualities of virtuous individuals while being influenced by jealousy and envy. Therefore, those who renounce envy and appreciate the virtues of enlightened beings like the Tirthankaras and strive to emulate them are truly praiseworthy.

-

Karunya Bhavana (Contemplation of Compassion): This Bhavana arises when, upon seeing the suffering of beings in the world due to karma, one's heart is filled with compassion. The desire to alleviate the suffering of others arises from this Bhavana. Those who practice Karunya Bhavana understand that suffering results from unrighteousness and strive to convert the unrighteous lives of others into righteous ones. Such individuals, using their fortunate circumstances and abilities, act for the welfare of themselves and others. By practicing this Bhavana with discernment, one acquires virtues like generosity and eventually contributes to the protection of all beings.

-

Madhyastha Bhavana (Contemplation of Equanimity/Indifference): In this transient world, souls, in their pursuit of happiness, commit terrible sins without hesitation. Some even condemn the omniscient beings and their teachings. Madhyastha Bhavana involves remaining indifferent to such unworthy beings, without developing hatred towards them. Those who practice this Bhavana understand that even the omniscient Arihants cannot reform such individuals, let alone themselves. Since such beings are destined to wander in samsara due to their karma, attempting to reform them is futile and only leads to self-harm. It is foolish to strive for the welfare of others at the cost of one's own well-being. If one holds a position of responsibility, the best course of action is to provide general guidance and then ignore them. The text emphasizes that even with the best spiritual resources, if someone does not wish to practice religion or understand explanations, their indifference is in the best interest of both parties.

Part 2: Panch Parmeshthi Gun Darshan (Vision of the Virtues of the Five Supreme Beings)

This section is dedicated to enumerating and describing the virtues of the Five Supreme Beings of Jainism: Arihants, Siddhas, Acharyas, Upadhyayas, and Sadhus.

-

Arihants: The text details the twelve supreme attributes (Pratiharyas) of the Arihant, such as the celestial flower shower, divine music, the parasol, the divine announcement, and special powers like the "Apaya-apagamatishaya" (eradication of epidemics and calamities), knowledge, worship, and speech.

-

Siddhas: It then lists the eight eternal virtues of the Siddhas, who have attained liberation: infinite knowledge, infinite perception, unobstructed bliss, infinite conduct, eternal existence, formlessness, immutability (agurulaghu), and infinite power.

-

Acharyas: A significant portion is dedicated to the thirty-six virtues of Acharyas, covering their control over the five senses, their strict adherence to the vows (Mahavratas), particularly the vow of celibacy (Brahmacharya) with its nine safeguards, their renunciation of anger, pride, illusion, and greed, and their adherence to the codes of conduct related to knowledge (Jnanaachar), perception (Darshanachar), conduct (Charitraachar), penance (Tapachar), and energy (Veeryachar). It also describes their meticulous practice of the five Samitis (carefulness) and three Guptis (restraint).

-

Upadhyayas: The text lists the virtues of Upadhyayas, focusing on their profound knowledge of the various Jain scriptures (Angas and Upangas). Their role as teachers is highlighted, emphasizing their dedication to imparting knowledge and their adherence to various rules and disciplines (like the 70 types of conduct mentioned).

-

Sadhus: Finally, the virtues of Sadhus are described, including their strict adherence to the five Mahavratas, their protection of the six types of living beings (Jivas), their control over the five senses and four passions, their practice of the twelve Bhavanas, and their adherence to various disciplinary measures and austerities.

In essence, the book serves as a guide for spiritual aspirants, first by outlining the essential contemplative practices for detaching from worldly entanglements and then by providing a detailed vision of the exemplary qualities of the highest spiritual beings in Jainism, encouraging devotees to strive towards these ideals.