Bharatiya Tattvagyan

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Bharatiya Tattvagyan - Ketlika Samasya" by Nagin J. Shah, based on the provided pages:

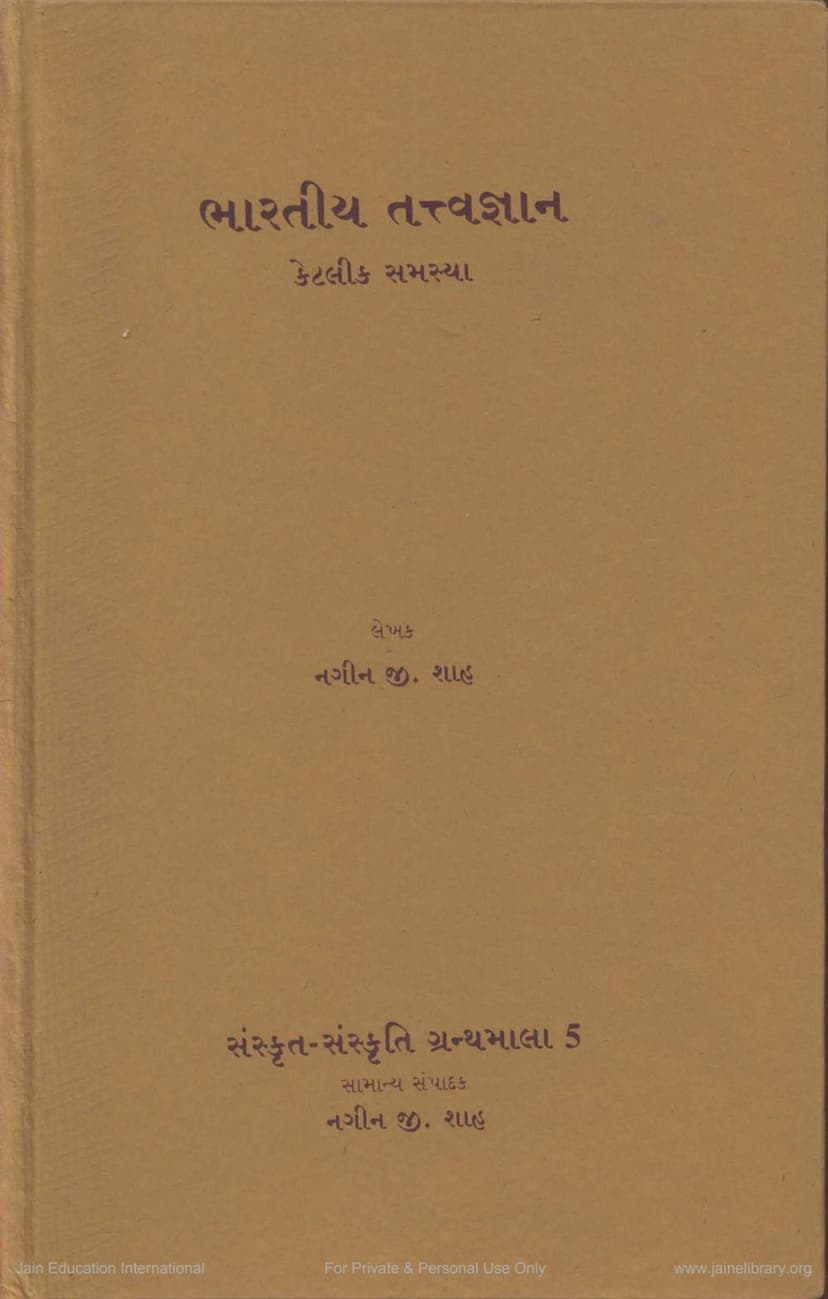

Book Title: Bharatiya Tattvagyan - Ketlika Samasya (Indian Philosophy - Some Problems) Author: Nagin J. Shah Publisher: Dr. Jagruti Dilip Sheth Language: Gujarati Subject: Indian Philosophy

Overview:

"Bharatiya Tattvagyan - Ketlika Samasya" by Nagin J. Shah, published in 1998, is the fifth book in the Sanskrit-Sanskriti Granthmala series. The book offers a sincere effort to present the views of various Indian philosophical traditions on significant philosophical problems. It aims to provide a balanced presentation of the arguments supporting different viewpoints, along with a critique of those arguments, making it a satisfying read for scholars and curious minds alike. The book is based on original Sanskrit texts, providing appropriate references to ensure its authenticity and reliability.

Key Themes and Chapters:

The book is structured into seven chapters, each addressing a fundamental problem in Indian philosophy:

-

Sat-Asat (Existence and Non-existence):

- This chapter delves into the philosophical discourse surrounding the dual concepts of existence (Sat) and non-existence (Asat).

- It traces the historical development of this debate from the Rigveda, where the concept of "Sat" was understood as a commonality among deities, through the Upanishads, where the origin of existence from non-existence (or vice versa) was discussed.

- The chapter explores the contrasting theories of Satkaryavada (the effect pre-exists in the cause, as in Samkhya) and Asatkaryavada (the effect does not pre-exist in the cause, as in Nyaya).

- It also examines the Buddhist concept of Vibhajyavada, where only momentary dharmas are considered "Sat," and the Vijñānavāda and Shunyavada schools' views on reality.

- The chapter concludes by discussing the definitions of "Sat" provided by various schools like Buddhism (momentariness), Shankar Vedanta (transcendental permanence), Jainism (origination-decay-permanence), and Nyaya-Vaisheshika (being related to existence). The Buddhist concept of "Arthakriyakaritva" (causal efficacy) as a criterion for existence is highlighted.

-

Moksha Vichar in Indian Philosophies (Concept of Liberation in Indian Philosophies):

- This chapter defines Moksha (liberation) as freedom from suffering for the soul (Atman).

- It establishes the prerequisite acceptance of the soul's existence, the reality of suffering, the causes of suffering, the means to overcome suffering, and the possibility of liberation.

- It then surveys the different conceptions of the soul (Atman) across various Indian philosophical systems: Charvaka (materialistic), ancient Samkhya, Jainism, Buddhism (consciousness/mind as the soul), post-Samkhya (Atman distinct from consciousness), Nyaya-Vaisheshika (Atman as an immaterial substance with intelligence as a quality), and Shankar Vedanta (Atman as Brahman).

- The chapter discusses the differing views on the nature of the liberated soul: whether it experiences positive, pure bliss or remains devoid of such states, and whether it possesses knowledge in the state of liberation.

- It also examines the arguments for the possibility of Moksha and the methods to achieve it, emphasizing the destruction of attachment and aversion (Raga-Dvesha) as the root cause of suffering and the importance of practices like Ashtanga Yoga.

-

Karma and Rebirth:

- This chapter posits that the law of cause and effect operates in the moral realm, just as it does in the physical world, forming the basis of the Karma theory.

- It addresses the apparent disparity in life, where good people suffer and bad people prosper, explaining this through the concept of rebirth, where the fruits of actions are experienced across lifetimes.

- Evidence for rebirth is presented through the phenomena of infant fear of frightening objects (attributed to memory from past lives) and instances of recollection of past lives (Jatismaran).

- The chapter traces the concept of Karma and rebirth from the Rigveda, through the Upanishads (mentioning Nachiketa's understanding), and the Bhagavad Gita (emphasizing detachment from fruits of action and the cyclical nature of birth and death).

- It discusses the Buddhist doctrine of Karma and rebirth, highlighting the Pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination) and the twelve links of Bhavacakra (wheel of existence). It differentiates between auspicious (Kushala) and inauspicious (Akushala) actions, and the concept of Nirvana.

- The Nyaya-Vaisheshika perspective on Karma and rebirth is also explored, including the concept of Adrishta as the unseen force that mediates the results of actions.

- Jainism's unique materialistic conception of Karma (Pudgala) as subtle particles that attach to the soul, influencing its qualities and future births, is detailed.

-

Ishvara (God) in Indian Philosophies:

- This chapter divides Indian thinkers into two categories regarding their concept of Ishvara: those who accept a singular, eternal, creator God (like later Nyaya-Vaisheshika and Vedanta), and those who consider liberated beings who guide others to liberation as Ishvara (like Jainism, Buddhism, Patanjali Yoga, and early Nyaya-Vaisheshika).

- Jainism and Buddhism: Reject the notion of a creator God and consider liberated souls (Tirthankaras in Jainism, Buddhas in Buddhism) as the highest beings who guide others.

- Samkhya: Is atheistic, believing that the world arises from the interaction of Purusha and Prakriti.

- Yoga: Posits Ishvara as a special Purusha, untouched by afflictions, karma, or fruits, who is the source of all knowledge and the teacher of the earliest teachers. This Ishvara is not a creator but a supreme, ever-free Purusha.

- Nyaya-Vaisheshika: The early Nyaya-Vaisheshika schools were likely non-theistic, with the concept of a creator God being introduced later, possibly influenced by Puranic traditions. The Upaskara commentary on Vaieshika Sutras and later thinkers like Vatsyayana and Uddyotakara present the idea of a creator God, but the exact nature and function of this Ishvara are debated. Uddyotakara argues for an Ishvara as the efficient cause behind the atomic world and the force that makes atoms move. Jayanta Bhatta defends Ishvara's existence through arguments like causality and the need for a divine teacher for ultimate knowledge. Shri Dhar attempts to reconcile Ishvara's role with Karma theory. Udayana presents detailed logical arguments for God's existence as the creator, controller, and granter of liberation, emphasizing His omniscience and omnipotence.

- Mimamsa: Primarily focuses on Vedic rituals and their efficacy, generally rejecting a creator God. However, later Mimamsa thinkers, influenced by Puranic traditions, accepted a role for Ishvara as a giver of fruits of action.

- Vedanta: Presents a more elaborate concept of Ishvara as Brahman with attributes (Saguņa Brahman), the creator, sustainer, and destroyer of the universe, who is also the inner controller (Antaryami) of all beings. Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita, Madhva's Dvaita, Nimbarka's Dvaitadvaita, and Vallabha's Shuddhadvaita all offer distinct perspectives on Ishvara's relationship with the world and individual souls.

-

Jñāna Viṣayaka Samasyāōno Sāmānya Parichay (General Introduction to Problems Related to Knowledge):

- This chapter introduces the fundamental epistemological questions in Indian philosophy: How can we know reality? What are the valid means of knowledge (Pramanas)? How do we determine the validity of knowledge? How do we know knowledge itself?

- It begins by defining "Prama" (valid knowledge) as that which accurately reflects reality, free from defects.

- It outlines the different schools' views on the criteria for valid knowledge and the sources of knowledge.

-

Jñāna nu Pramāṇya svataḥ ke paraḥ? (The Validity of Knowledge: Intrinsic or Extrinsic?):

- This chapter delves into the epistemological debate about the origin of the validity of knowledge.

- It discusses the Mimamsa position that the validity of knowledge is intrinsic (svatah), meaning it is known along with the knowledge itself.

- In contrast, the Nyaya-Vaisheshika and some Buddhist schools argue that the validity of knowledge is extrinsic (paratah), meaning it is known through other means, such as successful action or subsequent knowledge.

- The chapter presents the arguments and counter-arguments of these schools, highlighting the complexities of determining the source of certainty in knowledge.

-

Bhāratīya Tārkikōni Pratyakṣa Viṣayaka Charchā (Discussion on Perception by Indian Logicians):

- This chapter focuses on the different theories of perception (Pratyaksha) in Indian logic.

- It examines the distinction between Nirvikalpaka (indeterminate) and Savikalpaka (determinate) perception, and how different schools define and categorize them.

- It discusses the role of sense-object contact (Indriya-artha-sannikarsa) in the process of perception.

- The chapter explores the debates on whether perception is the only source of knowledge for direct experience or if other means are also involved.

- It highlights the challenges faced by logicians in defining Pratyaksha, particularly in reconciling it with concepts like yogic perception and the Buddhist doctrine of momentariness.

Overall Contribution:

"Bharatiya Tattvagyan - Ketlika Samasya" serves as a valuable resource for understanding the intricate philosophical landscape of India. By systematically addressing key problems and presenting diverse viewpoints with critical analysis, Nagin J. Shah provides readers with a comprehensive and insightful overview of Indian philosophical thought. The book's adherence to original texts and clear explanations makes it accessible to both seasoned scholars and those new to the study of Indian philosophy.