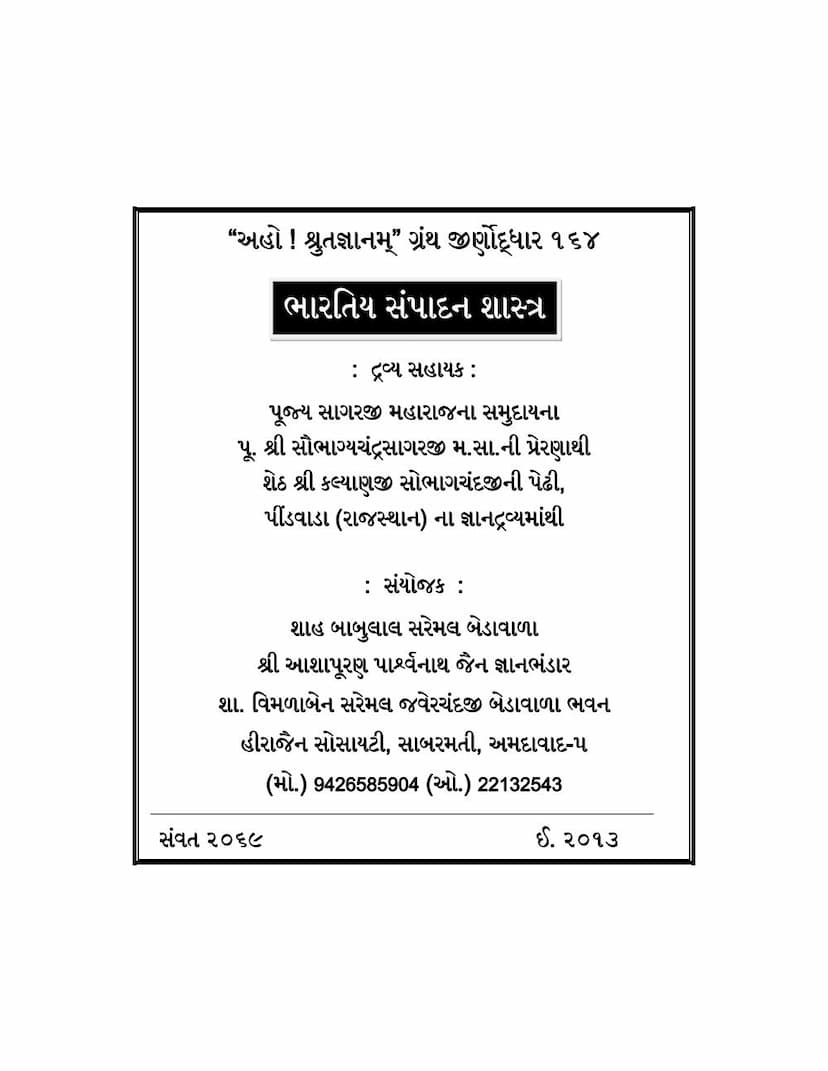

Bharatiya Sampadan Shastra

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

The provided text is a detailed exploration of the principles and practices of Bharatiya Sampadan Shastra (Indian Textual Criticism or Editing Science), authored by Mulraj Jain. The book, published by Jain Vidya Bhavan and supported by the Jain Shwetambar Terapanth community, is part of a larger project to digitize and preserve rare Jain manuscripts. The text itself is a reprint from the November 1942 issue of the Oriental College Magazine, Lahore.

The book is structured into several chapters that systematically address the complexities of editing ancient Indian texts, particularly those prevalent in Jain traditions. Here's a comprehensive summary of its key themes:

I. Introduction (Page 12-13):

- The author begins by expressing gratitude for a research scholarship that allowed him to work under Dr. Lakshman Swaroop, a renowned Indian scholar.

- He emphasizes that textual criticism has become a "science" with its own principles, essential for successful editing.

- The goal is to reconstruct the original or earliest form of ancient texts, acknowledging the contributions of Western scholarship in this field.

- The work is dedicated to assisting those who understand Sanskrit and Hindi in their own editing endeavors.

- The author acknowledges the significant works of scholars like I.S. M. Katre, F. W. Hall, V. S. Sukthankar, F. Edgerton, L. Sarup, and G. H. Ojha, whose research has informed his own.

II. Definition and Scope of Textual Criticism (Page 14-15):

- Textual criticism is defined as the science of revising ancient works using available manuscripts to achieve the author's original intent or the text's earliest state.

- It involves understanding the relationships between manuscripts, identifying their original sources, tracing the evolution of textual changes, determining the oldest readings, and correcting inaccuracies.

- The term "rachana" (composition) encompasses various forms like "pust," "pustak," "pothi," "sutra," "granth," and "kriti."

- The origin of terms like "pustak" and "granth" is linked to the binding of manuscripts, which were often written on materials like palm leaves, birch bark, paper, wood, or cloth.

III. Historical Context of Writing in India and Challenges in Manuscript Preservation (Page 15-18):

- The author addresses the scarcity of very ancient manuscripts in India.

- He discusses early Indian scripts like Brahmi and Kharosthi, and mentions the discovery of Indus Valley Civilization scripts, suggesting an ancient tradition of literacy.

- Reasons for the lack of old manuscripts are explored, including:

- Emphasis on Memory: Traditional Indian education prioritized memorization, especially for Vedic texts, due to the need for precise pronunciation. Written texts were sometimes discouraged in this context.

- Perishability of Materials: Ancient writing materials were not always durable, leading to the decay of manuscripts over time.

- Religious Practices: The tradition of immersing used manuscripts in holy rivers.

- Historical Disruptions: Wars, invasions, and other events led to the destruction of written materials.

- The author notes that Jain and Buddhist traditions have clearer records of when their religious literature was codified and written down.

IV. Classification of Literature and Manuscript Transmission (Page 18-21):

- Literature is divided into two categories:

- Samashti-rachita Sahitya (Collectively Composed Literature): This includes works where a community or lineage of scholars contributed over time, like the Vedas. These texts often underwent changes due to oral transmission before being written down.

- Vyakti-rachita Sahitya (Individually Composed Literature): These are works primarily authored by specific individuals, who might have written or supervised the writing of their own manuscripts (Mula Prati). These tend to have a more direct transmission.

- The importance of manuscript circulation is highlighted, citing examples of travelers carrying vast numbers of books and the practice of gifting manuscripts.

V. Manuscript Materials and Characteristics (Page 21-25):

- Source Materials: Manuscripts were written on palm leaves, birch bark, cloth, wood, metal, stone, brick, and paper.

- Manuscript Features:

- Leaf Numbering: Typically, leaves are numbered, not pages.

- Writing Style: Words were often written consecutively, with occasional separators.

- Punctuation: Various punctuation marks were used, evolving over time.

- Symbols: Symbols were used for abbreviations or repetitions.

- Marginal Notes: Marginal notes and scribal colophons are common.

- Manuscript Preparation: Details on how palm leaves and birch bark were prepared are provided.

VI. The Role of the Scribe (Lipikar) (Page 25-28):

- The author discusses the profession of scribes, their evolution through different periods and names (Lipikar, Divirapati, Kayastha).

- He highlights the significant contribution of Jain monks and scholars in the creation and preservation of literature.

- Scribes are categorized based on their diligence and supervision: those working under authorial or scholarly guidance versus those working for livelihood.

- The author describes the scribe's process, emphasizing that copying is not simple and can lead to errors due to physical strain and cognitive lapses.

- Scribes sometimes acknowledged their errors or attributed them to the original manuscript, a practice that complicates modern editing.

VII. Types of Errors in Manuscripts and Their Causes (Page 35-56): This is a crucial and extensive section detailing various types of errors that occur in manuscripts and their underlying causes:

- Lipibhram (Script Errors): Confusion between similar-looking characters in a script or when transcribing between different scripts (e.g., Sharada to Devanagari).

- Shabd-bhram (Word Errors): Mistaking similar-sounding words with different meanings.

- Lop (Omission): Omission of letters, syllables, words, lines, or even pages due to scribe's inattention or similarity of textual elements.

- Aagam (Addition): Accidental or intentional addition of text.

- Abhyas (Repetition): Unintentional repetition of text.

- Vyatyay (Transposition): Reversal of letters, words, or lines, often due to manuscript damage or scribal confusion.

- Samanarth-shabdantar-nyas (Substitution of Synonyms): Replacing a word with a synonym, either intentionally or unintentionally.

- Inclusion of Marginal Notes: Marginal commentary or annotations being mistakenly included in the main text.

- Cognitive Lapses (Vichar-vibhra): Scribe's mind wandering or recalling unrelated passages.

- Phonetic Variations (Dhwani/Uchcharan): Errors arising from pronunciation differences or regional accents.

- Language Irregularities: Inconsistent spelling and grammar in vernacular texts.

- Language Shift: Introduction of Sanskrit words into Prakrit/Apabhramsa texts or vice versa.

- Substitution of Forms: Altering verb or noun forms based on grammatical analogies.

- Simplification of Difficult Passages: Replacing archaic or complex language with simpler equivalents.

- Chandobhanga (Metrical Errors): Violations of poetic meter.

- Prakshep (Interpolation): Deliberate addition of text, often by later scholars or readers to clarify, expand, or insert doctrinal material. This can include longer passages, verses, or even entire sections.

- Refinement of Descriptions: Elaborating on existing descriptions of events like battles or marriages.

- Repetition of Narratives: Repeating stories or accounts in different parts of a text.

- Inclusion of Didactic Material: Adding moral sayings or philosophical explanations.

- Filling Gaps: Completing missing portions of a damaged manuscript.

- Resolving Contradictions: Altering text to remove perceived inconsistencies.

VIII. Manuscript Collation and Reconstruction (Page 36-48):

- Collation (Pratiyon ka Milan): The process of meticulously comparing different manuscripts to identify variations. This involves systematically noting down readings for each segment of the text.

- Reliability of Manuscripts: The author stresses that the number of manuscripts is less important than their age, genealogical relationship (family tree of manuscripts), and the quality of their lineage.

- Manuscript Families: Manuscripts often fall into families or lineages based on shared readings and hypothetical common ancestors (mula-adarsha).

- Pure vs. Mixed Relationships: Distinguishing between manuscripts that closely follow a single tradition (pure) and those that incorporate readings from multiple traditions (mixed/sankirna). Mixed traditions are more complex to edit.

- Reconstruction Methods:

- Identifying Original Readings: The principle that readings common to all manuscripts are likely original.

- Evaluating Variants: Analyzing readings based on language, script, and contextual suitability (vishayanusangati and lekhanusangati).

- Reconstructing Hypothetical Ancestors: Creating hypothetical intermediary manuscripts to trace the text's transmission.

- Rules for Selection: Prioritizing difficult readings over easy ones, and shorter readings over longer ones, as scribes tend to simplify or expand text.

- Identifying Doubtful Readings: Acknowledging passages where the original reading remains uncertain.

IX. Principles of Textual Correction (Page 56-68):

- Need for Correction: Recognizing that reconstructed texts may still contain errors.

- Correction Criteria: A corrected reading must be both contextually appropriate (vishayanusangat) and plausible as a scribal error or development (lekhanusangat).

- Two Editorial Approaches:

- Ancient Method: Adhering strictly to the manuscript readings, interpreting them as best as possible, and attributing any apparent errors to the author.

- Modern Method: Actively correcting errors based on scholarly principles, while clearly indicating the original readings in footnotes or appendices. The author favors this approach for clarity and accuracy.

- Balancing Correction and Interpretation: Finding a middle path between over-correction and slavish adherence to manuscript readings.

- Mahabharata and Correction: The author notes that the Pune edition of the Mahabharata adopted a conservative approach to corrections, focusing on resolving contradictions rather than emending every perceived flaw due to the vastness and historical distance from the text.

- Individual vs. Collective Works: Correction is more straightforward for individually authored works where authorial style and intent can be more readily discerned.

- The Process: Emphasizing systematic collation, critical analysis of variants, and careful consideration of linguistic and historical context for both reconstruction and correction.

- Acceptance, Doubt, Rejection, and Emendation: Outlining the possible outcomes of textual analysis for each reading.

X. Appendices:

- Appendix 1: Methods of Manuscript Collation: Provides a practical guide on how to prepare and compare manuscripts systematically, including the use of index cards and noting down variants.

- Appendix 2: Ancient Writing Materials: A detailed account of the various materials used for writing in ancient India, including palm leaves, birch bark, cloth, wood, metals (especially copper for inscriptions), leather, stone, bricks, and paper, along with their preparation and usage.

- Appendix 3: Catalogues of Manuscripts: Lists significant catalogues of Indian manuscripts compiled in India and abroad, highlighting the systematic efforts to document and preserve this literature.

In essence, "Bharatiya Sampadan Shastra" is a scholarly treatise that delves into the scientific methodology of critically editing ancient Indian texts. Mulraj Jain meticulously explains the challenges posed by manuscript variations, the historical context of their transmission, the types of errors introduced by scribes, and the systematic approaches required for reconstruction and correction to arrive at the most authentic version of a text. The book serves as a comprehensive guide for scholars engaged in the crucial task of preserving and understanding India's rich literary heritage.