Bharatiya Darshanoma Parinamvad

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Bharatiya Darshanoma Parinamvad" by Vasant Parikh, focusing on the concept of Parinamvad (theory of transformation/evolution) across various Indian philosophical schools, with an emphasis on Jainism, as presented in the provided text:

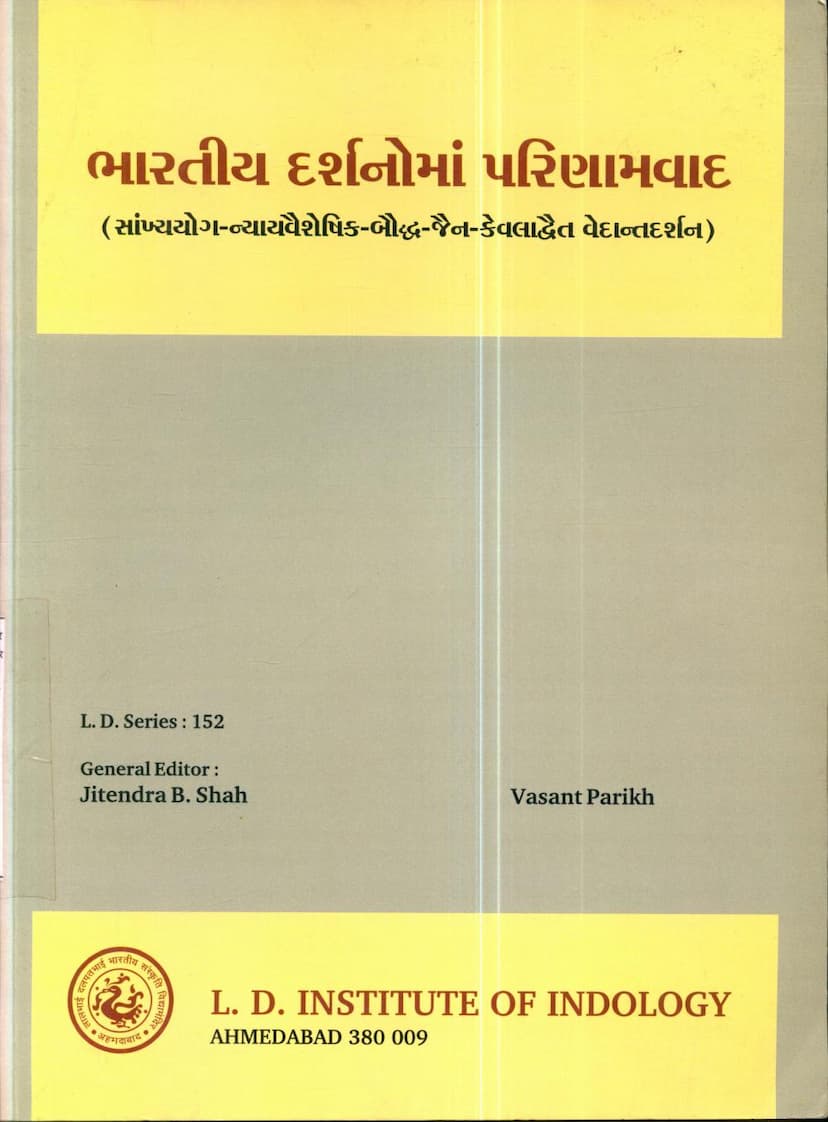

Book Title: Bharatiya Darshanoma Parinamvad (Parinamvad in Indian Philosophies) Author: Vasant Parikh Publisher: L D Indology Ahmedabad Published: 2012

Overall Theme: This book is a scholarly exploration of the concept of "Parinamvad" – the doctrine of transformation, evolution, or causation – as understood and articulated within different schools of Indian philosophy. The author, Vasant Parikh, delves into the nuances of this concept in Samkhya-Yoga, Nyaya-Vaisheshika, Bauddha (Buddhist), Jaina, and Kevaladvaita Vedanta philosophies. The aim is to present a comparative analysis of how these traditions explain the origin, nature, and ongoing processes of change and development in the universe.

Key Schools and their Parinamvad:

-

Samkhya-Yoga:

- Samkhya is considered one of the earliest Indian philosophies to significantly address the principles of cosmic evolution.

- It posits a dualistic framework with two fundamental, independent, and eternal substances: Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (primordial matter/nature).

- Prakriti, characterized by the equilibrium of three gunas (Sattva, Rajas, Tamas), is the ultimate material cause of the universe.

- The evolution or "parinaman" of the universe begins when this equilibrium is disturbed, often attributed to the proximity or presence of Purusha, leading to the manifestation of various principles like Mahat (Intellect), Ahamkara (Ego), Manas (Mind), Indriyas (senses), Tanmatras (subtle elements), and Mahabhutas (gross elements).

- Samkhya's explanation of creation is a process of Parinamavada (transformation), where the effect (creation) is inherently present in the cause (Prakriti) in a subtle form. This is known as Satkaryavada (the doctrine that the effect pre-exists in the cause).

- The book highlights the Samkhya classification of tattvas (principles) into Prakriti (unmanifest, the root cause), Prakriti-vikriti (seven principles that are both effects and causes, e.g., Mahat, Ahamkara, five Tanmatras), and Vikara (sixteen principles that are only effects, e.g., Mind, eleven Indriyas, five Mahabhutas). Purusha is considered neither a cause nor an effect, being eternal and unchanging.

- The concept of the three gunas and their interaction (visamya) is central to understanding how Prakriti transforms.

-

Nyaya-Vaisheshika:

- These schools are more concerned with epistemology (Pramanashastra) and metaphysics (Padarthashastra), respectively, but they also have a theory of causation.

- They are fundamentally atomistic and propose that the universe is composed of eternal, indivisible atoms (Paramanu).

- The process of creation begins with God's will (Ishvara) activating these atoms.

- Their view on causation is Asatkaryavada (the doctrine that the effect does not pre-exist in the cause) or Arંભavada (the doctrine of origination). According to this, effects are entirely new creations that emerge from the combination of atoms, previously non-existent in that form.

- The book explains the Nyaya-Vaisheshika concept of seven Padarthas (categories): Dravya (substance), Guna (quality), Karma (action), Samanya (generality), Vishesha (particularity), Samavaya (inherence), and Abhava (non-existence). The evolution of the world is explained through the interaction of Dravyas (like atoms) and their qualities.

- The concept of Samavaya (inherence) is crucial for explaining how qualities adhere to substances and how composite substances are formed from their constituent parts (like threads forming a cloth).

- The book points out the Nyaya-Vaisheshika rejection of Samkhya's Satkaryavada, arguing that if effects were always present in the cause, then effects would be identical with the cause, rendering the distinction meaningless. They emphasize the creation of something entirely new.

-

Bauddha (Buddhist) Philosophy:

- The core of Buddhist philosophy, as presented by the Buddha, is the understanding and cessation of suffering through the Four Noble Truths.

- A central tenet is Anityata (impermanence) and Kshanikavada (momentariness). The Buddhist view is that everything is in a constant state of flux; nothing remains the same even for two consecutive moments.

- This constant change is not a transformation of an underlying substance but rather a succession of momentary entities.

- The doctrine of Pratityasamutpada (Dependent Origination) explains the causal chain that leads to suffering, where each phenomenon arises in dependence on another. This forms a twelve-linked chain starting from Avidya (ignorance).

- The Buddhist concept of causation is also a form of Asatkaryavada, where the effect is not pre-existent in the cause. However, it differs from Nyaya-Vaisheshika in that the cause itself is also momentary and ceases to exist immediately after giving rise to the effect.

- The book notes that different schools within Buddhism (e.g., Vaibhashika, Sautrantika, Yogachara, Madhyamaka) have varying interpretations of reality and causation, but the underlying principle of impermanence and the rejection of a permanent, underlying substance (like the Samkhya Purusha or Atman) is common.

-

Jaina Philosophy:

- Jainism is characterized by its pluralistic and realistic approach, accepting the existence of multiple, distinct eternal substances (Dravyas).

- Jainism is a Parinamavadi philosophy because it posits that every substance possesses inherent transformative potential and undergoes continuous modification.

- The core substances are Jiva (soul/consciousness) and Ajiva (non-soul/matter), along with other categories related to bondage and liberation (Bandha, Asrava, Samvara, Nirjara, Moksha).

- Jainism accepts Satkaryavada in a modified sense: while the effect pre-exists in the cause, the cause undergoes a transformation (Parinama) to manifest the effect. The substance remains the same in its essential nature (Dravya), but its modifications or states (Paryaya) change.

- The famous Jain doctrine of Anekantavada (multiplicity of viewpoints) or Syadvada (the doctrine of conditioned predication) is crucial here. It suggests that reality is multifaceted, and different perspectives can reveal different aspects of it. This allows for the acceptance of both permanence (of the underlying substance) and change (in its states).

- Jainism explains transformation through Dravya-Guna-Paryaya: Dravyas are the eternal substances, Gunas are their inherent qualities (which are also considered eternal), and Paryayas are the transient states or modifications of these qualities and substances.

- The book highlights the Jain view that the soul (Jiva) has infinite qualities, but these are often obscured by karma. The process of liberation involves shedding these karmic obscurations through right faith, knowledge, and conduct (Ratnatraya), allowing the soul to manifest its inherent pure qualities.

- Jainism views the universe as a continuous play of transformation where substances undergo changes in their Paryayas, but the underlying Dravya remains.

-

Kevaladvaita Vedanta:

- Advaita Vedanta, particularly in the "Kevaladvaita" (absolute monism) tradition as expounded by Adi Shankaracharya, presents a different perspective on causation and transformation.

- The ultimate reality is Brahman, which is one, unchanging, and without attributes (Nirguna Brahman).

- The perceived world of multiplicity and change is considered Maya or Avidya (ignorance), a cosmic illusion or superimposition on Brahman.

- From this perspective, the universe is not a real transformation of Brahman but a Vivarta (unreal manifestation or appearance). Brahman itself remains unchanged.

- Shankara's philosophy is called Vivartavada (doctrine of appearance/superimposition). It states that the world appears to be real and evolving due to Maya, but ultimately, it is non-real from the absolute perspective.

- The book contrasts this with Parinamavada, where the cause genuinely transforms into the effect (like Samkhya). In Vivartavada, the cause does not transform; it merely appears differently due to an illusion.

- The famous analogy of the rope and the snake is used: the rope is real, but due to darkness (Maya), it appears as a snake. The snake is a Vivarta of the rope. When the light (knowledge) comes, the snake disappears, but the rope remains as it was.

- This view, while accepting the empirical reality of the world for practical purposes (Vyavaharika Satya), ultimately negates its absolute reality (Paramarthika Satya).

Common Threads and Divergences: The book notes that while each philosophy has its unique approach, there are common underlying quests:

- Search for Truth: All schools aim to understand the fundamental nature of reality and provide a path to liberation from suffering.

- Causality and Transformation: The concept of how the universe comes into being and undergoes change is a central theme, with differing views on whether this is a real transformation (Parinama) or an apparent one (Vivarta) or a new creation (Arંભavada).

- Role of Intellect and Scripture: Most philosophies rely on logical reasoning and intellectual analysis, but also refer to the authority of scriptures (Agamas, Vedas, Upanishads) when needed.

- Emphasis on Consciousness: Except for Charvaka (materialism), all schools acknowledge the existence of consciousness or a conscious principle (Purusha in Samkhya, Atman in Vedanta, soul in Jainism, momentary consciousness in Buddhism).

Concluding Remarks: The author concludes by emphasizing that despite their differences, Indian philosophies contribute to a broader understanding of existence. They start by accepting the empirical reality of the world and then move towards higher truths. The ultimate goal for most is liberation from suffering and the attainment of true self-knowledge. The author acknowledges the limitations of covering the entire philosophical landscape but aims to provide a foundational understanding of Parinamvad in these major Indian traditions.

This summary captures the essence of Vasant Parikh's work, highlighting the diverse interpretations of transformation and causation across key Indian philosophical schools, with a specific focus on the Jain perspective.