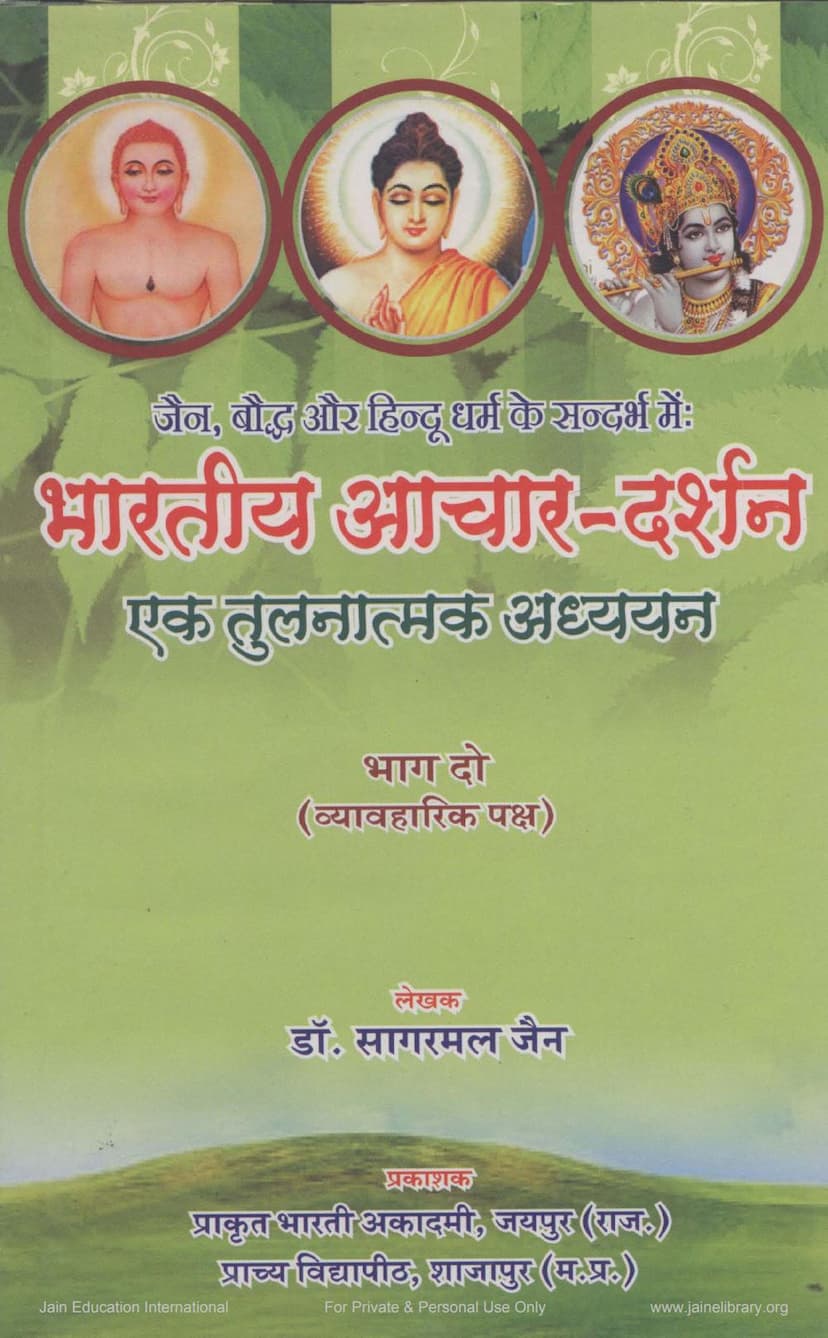

Bharatiya Achar Darshan Part 02

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Bharatiya Achar Darshan Part 02" by Sagarmal Jain, focusing on its comparative study of ethical philosophies within Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism:

Book Title: Bharatiya Achar Darshan Part 02 (Indian Ethical Philosophy Part 02) Author: Dr. Sagarmal Jain Publisher: Prakrit Bharti Academy, Jaipur (Rajasthan); Prachy Vidyapith, Shajapur (Madhya Pradesh) Focus: A Comparative Study of Ethical Philosophies in Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism (Practical Aspect)

Overall Scope and Purpose:

This book, the second part of a larger comparative study, delves into the practical aspects of ethical philosophy across three major Indian traditions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism (with a particular focus on the Bhagavad Gita). The author, Dr. Sagarmal Jain, aims to bridge the perceived divides between religions by highlighting their shared ethical principles and offering a balanced, harmonious perspective. The work stems from a comprehensive research thesis written approximately 40 years prior.

Key Themes and Approach:

The book emphasizes a comparative and harmonious approach, seeking commonalities and synthesizing the ethical teachings of these traditions rather than focusing solely on differences or criticisms. The author highlights the need for such studies in an era seeking social consciousness, tolerance, and coexistence.

Structure and Content:

The book is organized into several chapters, each examining a fundamental ethical concept from a comparative standpoint. Here's a breakdown of the major themes covered in the chapters, based on the provided table of contents:

-

Chapter 1: Samatva-Yoga (Equanimity-Yoga): This chapter establishes equanimity as the central element of ethical conduct. It explores the concept of Samatva-Yoga in Jainism, Buddhism, and the Gita, detailing its meaning as the state of being equipoised amidst dualities like pleasure and pain, gain and loss. The text elaborates on the causes of disharmony (like attachment, aversion, and ignorance) and how equanimity, achieved through practices like detachment, non-aggression in thought, non-possession, and non-violence, is the path to inner balance and spiritual liberation.

-

Chapter 2: Trividh Sadhana-Marg (The Threefold Path of Practice): This chapter focuses on the foundational triad of spiritual practice: Right Faith (Samyak Darshan), Right Knowledge (Samyak Gyan), and Right Conduct (Samyak Charitra). It compares these principles in Jainism, Buddhism (as Prajna, Sheela, and Samadhi), and the Gita (as Gyan Yoga, Karma Yoga, and Bhakti Yoga). The author discusses the interrelationship between these three, the philosophical underpinnings, and their role in achieving liberation. Western ethical concepts are also briefly compared.

-

Chapter 3: Avidya (Mithyatva) (Ignorance/False Belief): This chapter analyzes the concept of ignorance or false perception (Avidya or Mithyatva) as the root cause of suffering and unethical behavior across the traditions. It details the various classifications of ignorance in Jainism (e.g., Ekant, Viparit) and its manifestations in Buddhist and Vedic thought, including Western philosophical parallels like ingrained biases and illusions. The text emphasizes how ignorance clouds true understanding and leads to a distorted view of reality, consequently hindering ethical progress.

-

Chapter 4: Samyag-Darshan (Right Faith/Perception): This chapter delves into the meaning and significance of Samyak Darshan (Right Faith or Perception) in Jainism, its place in Buddhist thought (as Samma Ditthi), and its equivalent in Vedic traditions (as Shraddha or faith, particularly in the Gita). It explores the various classifications and components of Right Faith in Jainism, including its nine constituents and eight observances (Darshanachara). The interconnectedness of faith, knowledge, and conduct is highlighted.

-

Chapter 5: Samyag-Gyan (Right Knowledge/Knowledge Yoga): This chapter examines the role of Right Knowledge (Samyak Gyan) in Jain ethics, comparing it with Prajna in Buddhism and Gyan Yoga in the Gita. It discusses the nature of knowledge, differentiating between intellectual and spiritual knowledge, and emphasizes self-knowledge (Atma Gyan) as the ultimate goal. The text explores various methods for achieving self-knowledge, such as Bhed Vigyan (discrimination between the self and non-self) which is discussed in all three traditions.

-

Chapter 6: Samyak-Charitra (Right Conduct/Chastity): This chapter focuses on Right Conduct (Samyak Charitra or Sheel). It defines character as the practical manifestation of Right Faith and Right Knowledge. The discussion covers the different aspects and classifications of conduct in Jainism, Buddhism (as Sheela), and the Vedic tradition. The importance of ethical behavior, moral discipline, and the cultivation of virtues is emphasized.

-

Chapter 7: Samyak-Tapa and Yoga-Marg (Right Austerity and the Path of Yoga): This chapter explores the practice of austerity (Tapa) and the path of Yoga within the respective traditions. It examines the purpose and classification of austerity in Jainism (external and internal), its significance in Vedic traditions, and its role in Buddhist practices. The chapter also compares the concepts of Yoga, its eight limbs, and their presence or adaptation in Jainism.

-

Chapter 8: Nivritti-Marg and Pravritti-Marg (Path of Renunciation and Path of Action): This chapter tackles the philosophical distinction between the path of renunciation (Nivritti-Marg) and the path of action (Pravritti-Marg). It analyzes how Jainism and Buddhism lean towards renunciation, while the Gita attempts to synthesize both. The text discusses the concepts of householder dharma versus monasticism, escapism versus active engagement, spiritual versus material pursuits, and the debate between negative (prohibitory) and positive (prescriptive) ethics.

-

Chapter 9: Bharatiya-Darshan mein Samajik-Chetna (Social Consciousness in Indian Philosophy): This chapter investigates the development of social consciousness within Indian philosophical thought, tracing its roots from the Vedas and Upanishads through the Gita, Jainism, and Buddhism. It discusses concepts like social responsibility, the basis of social life (reason versus emotion), the role of ego and passions in social obstruction, the impact of renunciation on society, and the interplay between the four Purusharthas (goals of human life) and society.

-

Chapter 10: Swahit versus Lokhit (Self-Interest vs. Welfare of Others): This chapter addresses the ethical dilemma of prioritizing personal well-being versus the welfare of the community. It examines the Jain perspective on self-interest and altruism, the Buddhist focus on the welfare of the world, and the Gita's perspective on the relationship between self-interest and public good. It highlights the idea that true self-interest is intrinsically linked to the welfare of others.

-

Chapter 11: Varnashram-Vyavastha (Varna and Ashrama System): This chapter critically analyzes the Varnashram system within the context of Indian ethics. It explores the Jain and Buddhist views on caste, emphasizing their rejection of birth-based hierarchy and their focus on conduct and spiritual development. The chapter also discusses the Gita's interpretation of the Varnashram system, linking it to inherent qualities (Gunas) and actions (Karma). The concept of Ashrama (stages of life) is also briefly touched upon.

-

Chapter 12: Swadharma ki Avdharana (Concept of Self-Duty/One's Own Dharma): This chapter examines the concept of Swadharma (one's own duty or inherent nature) as presented in the Gita and Jainism. It explores the idea of fulfilling one's prescribed duties based on one's nature and societal role. The comparison highlights the subtle nuances and commonalities in how these traditions define and emphasize the importance of acting according to one's inherent nature and responsibilities.

-

Chapter 13: Samajik-Naitikata ke Kendriya Tattva: Ahimsa, Anagrah, aur Parigrah (Central Principles of Social Ethics: Non-violence, Non-attachment/Tolerance, and Non-possession): This pivotal chapter focuses on three core ethical principles central to Jainism and their comparative relevance in Buddhism and the Gita.

- Ahimsa (Non-violence): Explores the profound and all-encompassing nature of Ahimsa in Jainism, its psychological basis (respect for life, empathy), and its practical implications in social interactions. It compares this with Buddhist and Vedic concepts of non-violence, noting the exceptions and nuances in each tradition, particularly in the context of self-defense or unavoidable harm.

- Anagrah (Non-attachment to opinions/Tolerance): Examines Anagrah, often associated with Jainism's Anekantavada (multi-sided reality), as the principle of intellectual tolerance and open-mindedness. It contrasts this with rigid adherence to one's own views, highlighting how Anagrah promotes harmonious social discourse and reduces conflict. This is compared with Buddhist concepts of avoiding extreme views and the Gita's emphasis on detaching from outcomes.

- Aparigrah (Non-possession/Non-attachment): Discusses Aparigrah in Jainism, focusing on its extension to both material possessions and mental attachments. It explores its role in preventing greed, inequality, and social conflict. The chapter compares this with Buddhist concepts of detachment and the Gita's emphasis on renouncing the fruits of actions (Karma Phala Tyaga). The practical implications of non-possession for societal harmony are discussed.

-

Chapter 14: Samajik-Dharma evam Dayitva (Social Duty and Responsibility): This chapter details the various social duties outlined within Jain tradition, such as duties towards one's village (Gram Dharma), city (Nagar Dharma), nation (Rashtra Dharma), lineage (Kul Dharma), religious community (Sangh Dharma), and knowledge traditions (Shruta Dharma). It discusses the importance of upholding social norms, respecting elders and authorities, and contributing to the collective well-being. The chapter also touches upon Buddhist and Vedic perspectives on social duties and the concept of fulfilling one's societal obligations.

-

Chapter 15: Grihasth-Dharma (Householder's Duty): This chapter focuses on the ethical responsibilities and practices within householder life across the three traditions. It examines the path of a lay follower (Shravaka in Jainism, Upasaka in Buddhism), the vows and ethical guidelines they are expected to follow, and the concept of stages of spiritual progress within lay life. It compares the Jain Anuvratas and Guna Vratas with Buddhist Pancasila and Vedic Grihasthashrama duties. The role of principles like non-violence, truthfulness, non-stealing, chastity, and non-possession in householder ethics is detailed.

-

Chapter 16: Shraman-Dharma (Monastic Duty): This chapter elaborates on the rigorous ethical codes and practices expected of monastics (monks and nuns) in Jainism, Buddhism, and Vedic traditions. It discusses the core principles of monastic life, including the major vows (Mahavratas in Jainism, Pancasila for novices and Vinaya rules for monks in Buddhism, and the renunciate orders in Vedic tradition). The text details rules regarding conduct, austerity, celibacy, non-possession, and the importance of monastic discipline for spiritual liberation. It also discusses the classifications of monastics and the meticulous regulations governing their daily life, food, and interactions.

-

Chapter 17: Jain-Achar ke Samanya Niyam (General Principles of Jain Conduct): This chapter consolidates key Jain ethical principles applicable to both monastic and lay followers. It includes the Shat-Avashyak Karma (six essential duties), Dash Vidh Dharma (ten virtues), the importance of Dana (charity), Sheela (chastity/moral conduct), Tapa (austerity), and Bhava (inner disposition). It also touches upon the concept of contemplation (Anupeksha) and peaceful death (Samadhi Maran). The meticulousness of Jain ethical practices, even in seemingly minor details like conduct during daily routines, is highlighted.

Key Takeaways:

- Harmonious Approach: The book consistently seeks common ground and ethical synthesis between Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism, aiming to foster understanding and respect.

- Practical Ethics: It prioritizes the practical application of ethical principles in daily life for both householders and monastics.

- Interconnectedness of Principles: Jainism's core tenets of Ahimsa, Anekantavada (Anagrah), and Aparigrah are presented as interconnected principles crucial for social harmony.

- Emphasis on Inner Purity: While acknowledging the importance of external practices, the book underscores the ultimate goal of inner purity, mental equanimity, and self-realization as the true essence of ethical conduct.

- Social Responsibility: The text highlights the Jain emphasis on social responsibility, even within a renunciation-oriented tradition, through concepts like Parispargraha and contributing to the welfare of the community.

- Comparative Insight: The work provides valuable comparative insights into how these major Indian traditions address fundamental ethical questions, offering a rich tapestry of their practical moral philosophies.

This summary aims to capture the essence and breadth of "Bharatiya Achar Darshan Part 02." The book serves as a valuable resource for understanding the ethical dimensions of these influential Indian religions.