Ashtsahastri Part 3

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Ashtasahastri Part 3: A Comprehensive Summary

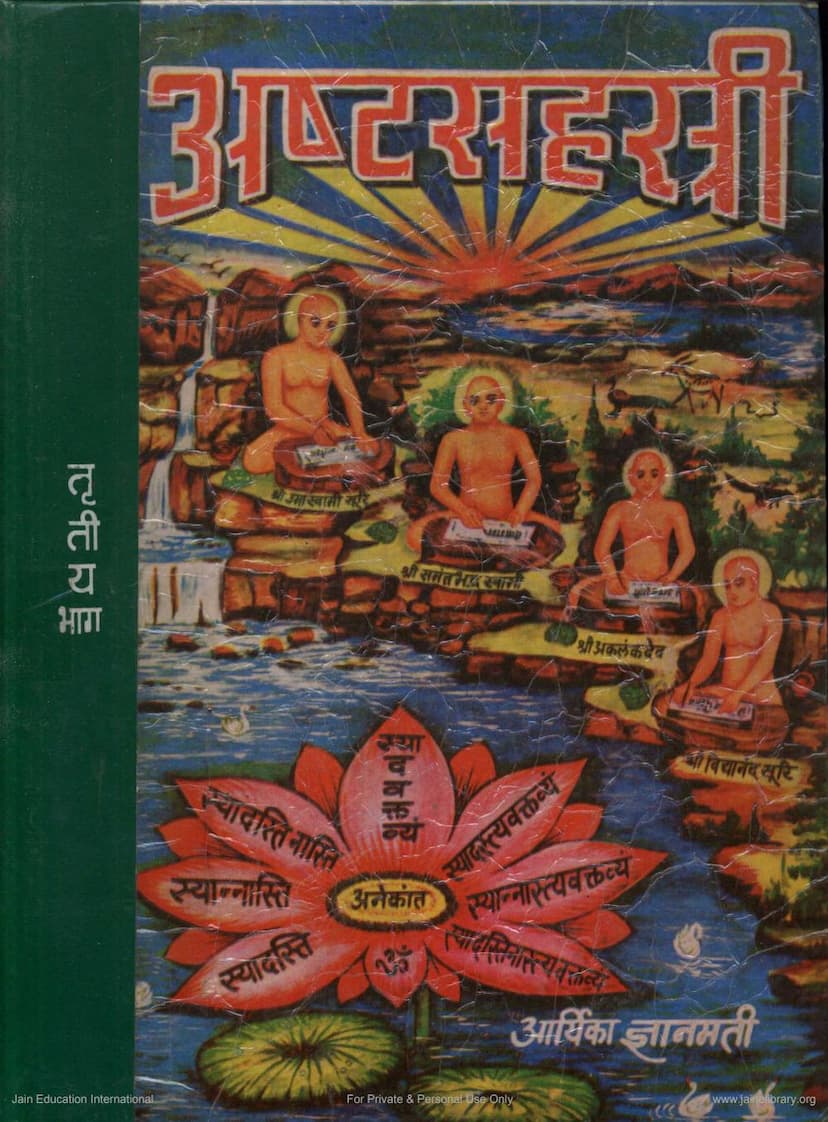

Book Title: Ashtasahastri Part 3 Author(s): Vidyanandacharya, Gyanmati Mataji Publisher: Digambar Jain Trilok Shodh Sansthan

This is a summary of Ashtasahastri Part 3, which covers the second to tenth chapters of the text, focusing on verses 24 to 114, along with a Hindi commentary titled "Syadvad Chintamani" by Aryika Gyanmati Mataji.

Overall Context:

Ashtasahastri is a significant work in Jain philosophy, serving as a commentary on the foundational Tattvartha Sutra. This third part of Ashtasahastri delves deeply into various philosophical schools and refutes their one-sided viewpoints (ekantavada) through the lens of Anekantavada (the Jain doctrine of manifold aspects) and Syadvada (the doctrine of conditional predication). The commentary by Aryika Gyanmati Mataji aims to make this complex philosophical text accessible to a wider audience.

Key Themes and Arguments (Chapter-wise Summary based on the "Vishay Darpan" - Subject Mirror):

Chapter 2: Refutation of Adwaitavada (Non-dualism)

- Introduction: Adwaitavada proponents establish their premise that creator (karta) and action (karma) distinctions are neither inherent nor external but exist nonetheless. The Acharya points out flaws in this.

- Argument against Brahman: If a soul, though indivisible, can be the basis for multiple causes in space, why can't Brahman, in the Adwaita view, be the basis for multiple causes? The Adwaitavadi believes Brahman permeates all conscious and unconscious entities.

- Agamas and Adwaita: Jain Acharyas critique the Adwaita claim to prove non-duality from scriptures (Agamas). They argue that scriptural statements often support duality, not non-duality.

- Self-Experience: The text discusses the Adwaita claim that Brahman is proven by self-awareness (swasamvedana). Jain Acharyas refute the idea that Brahman is self-proven.

- The Meaning of "Adwaita": The term "Adwaita" itself implies a negation of "Dwaita" (duality), thus requiring the existence of the very duality it seeks to negate.

- Philosophical Debates: The chapter engages with arguments for non-duality in the self (purusha-adwaita) and refutes concepts like "distinctness" (prithak-tva) as understood by Yoga and Vaisheshika. It also tackles the Buddhist concept of "stream of consciousness" (santan) and the idea of unity through proximity (pratyasatti).

- Critique of Idealism: The text examines the viewpoint of Advaitavada proponents who consider knowledge (jnana) to be different from the known (gyeya).

- Limitations of Language: If words cannot denote objects, their utterance is considered futile. The text critiques the notion that only words with a "three-faceted reason" (trirupa hetu) are true.

- Subjectivity and Reality: It questions the claim that knowledge neither determines its own nature nor that of others.

- Anekant in Existence: Jain Acharyas establish that oneness and otherness in entities like soul, etc., are only relative.

- Buddhist Nihilism: The text refutes the Buddhist view that only "intention" (vivaksha) is real and that non-intention (avivaksha) points to unreality.

- Nature of Proof: The chapter defines the characteristics of valid proof (pramana).

- Buddhist Atomism: It refutes the Buddhist assertion that direct perception (pratyaksha) reveals only atoms, not aggregates (skandhas), and the idea that atoms are real while aggregates are not.

Chapter 3: Refutation of Eternalism (Nitya Ekantavada)

- Samkhya's View of the Soul: Samkhyas consider the soul as inactive (akarta) and unchanging (aparinaami), while Jainism posits it as active and subject to transformation.

- The Self as Agent: The chapter addresses the Samkhya argument that the soul is the experiencer of consciousness and action.

- Activity of the Unchanging: It questions whether purposeful activity is possible for something eternally unchanging (kutashtha nitya).

- Change and Invariability: The text discusses the Samkhya distinction between change (parinama) and inherent nature (svabhava), with Jain Acharyas offering a refutation.

- Causality and Potency: It refutes the Samkhya view that causes and effects are eternally present in potency.

- The Nature of Origination and Cessation: The text defines origination (utpad) and cessation (vyaya) as manifestation (avirbhava) and disappearance (tirobhava).

- Eternal Cause and Effect: It critiques the Samkhya belief in eternal causes and effects.

- Pradhana (Primordial Matter): The chapter refutes the Samkhya concept of Pradhana as a mere transformation.

- Buddhist Impermanence: It refutes the Buddhist doctrine of momentariness (kshanikavada), arguing that it leads to problems with memory and the recognition of continuity (pratyabhijna). The text highlights how assuming utter momentariness leads to a denial of cause and effect, making destruction causeless.

- Causality and Substance: It explains that the transformation of a potent entity into its powers (shakti) is neither entirely different nor identical.

- The Nature of Cause: The chapter demonstrates that the impossibility of manifold effects without inherent differences in causes.

- The Buddhist View of Momentariness: It outlines the Buddhist position that the cessation of an entity immediately after a moment is its very nature.

- Uncaused Destruction: Jain Acharyas refute the Buddhist notion of causeless destruction.

- The Problem of Continuity: It addresses the Buddhist argument that if causes and effects are inherently different, how can continuity (sthiti) exist?

- Power and Substance: It questions the distinction between potent substance (shaktimaan) and power (shakti), whether they are identical or different.

- The Interdependence of Cause and Effect: The text proves that manifold effects are impossible without inherent differences in causes.

- The Nature of Momentariness: It describes the Buddhist view that the cessation of an entity immediately after a moment is its inherent nature.

- Causelessness: Jain Acharyas argue against the Buddhist concept of causelessness in existence and destruction.

- The Problem of Identity: It questions whether the continuity of an entity is fundamentally different or identical.

- The Unspeakable: The text addresses the Buddhist concept of the unspeakable (avaktavya) and its limitations.

- The Coexistence of Opposites: It clarifies how opposite qualities like presence (bhava) and absence (abhava) can coexist in a single entity.

- The Nature of Causality: The chapter analyzes the Buddhist perspective on causality and argues that both destruction (vinash) and origination (utpad) are caused.

- The Problem of Causelessness: It discusses the issue of causeless destruction and origination.

- The Problem of Causality in Different Streams: It examines the Buddhist idea of causality within a single stream of consciousness and across different streams.

- The Interdependence of Elements: The text discusses the interdependence of elements like threads and weaving in the creation of cloth.

- The Nature of Continuity: It addresses the question of whether continuity itself is eternal or transient.

- The Buddhist Concept of Continuity: It refutes the Buddhist notion of continuity being mere conventional reality (samvriti).

- The Problem of Fourfold Classification: It argues against the Buddhist attempt to classify every object into four categories.

- The Unspeakable: The text addresses the Buddhist concept that everything is ultimately unspeakable.

- The Problem of Negation: It critiques the idea that negation applies only to existent entities.

- The Coexistence of Opposites: It clarifies how presence (bhava) and absence (abhava) can exist in one entity.

- The Coexistence of Numbers: It explains how numbers like oneness and twoness can coexist in an entity without contradiction.

- The Meaning of Convention: It explores the meaning of convention (samvriti).

- The Unspeakable Nature of Reality: It questions why reality is considered unspeakable and addresses the nihilistic conclusion that the absence of reality leads to unspeakability.

- Causality of Destruction: It asserts that destruction is caused and, like origination, is not uncaused.

- The Relation of Destruction and Origination: It analyzes the relationship between destruction and origination.

- The Five Aggregates (Skandhas): It discusses the Buddhist concept of the five aggregates and their unreality.

- The Impossibility of Permanence in Unreal Aggregates: It argues that concepts like origination, cessation, and permanence cannot be applied to unreal aggregates.

- The Buddhist Denial of Recognition (Pratyabhijna): It refutes the Buddhist denial of recognition, asserting its validity according to Jain principles.

- Recognition as Independent Proof: It establishes recognition (pratyabhijna) as an independent valid means of knowledge (pramana).

- Recognition and Impermanence: While Buddhists deny recognition in momentary entities, Jainism accepts it in entities that are partially momentary.

- The Impossibility of Recognition Without Continuity: It asserts that recognition is impossible without a concept of continuity.

- The Impossibility of Recognition in Utter Permanence: It also states that recognition is impossible in entities of absolute permanence.

- The Nature of Change and Contradiction: It explains that despite inherent differences in origination, cessation, and permanence, contradictions are not necessarily implied.

- The Dynamic and Static Nature of Objects: It supports the idea that all objects possess both dynamic and static aspects.

Chapter 4: Refutation of Other Ekantas (One-Sided Views)

- Refutation of Pluralism (Bheda Ekanta): The Yoga school asserts that causes and effects, qualities and substances, parts and wholes are all distinct. They posit a "samavaya" relationship to connect them. Jainism argues that this distinction leads to contradictions, particularly regarding the inseparability of qualities and substances.

- Refutation of Monism (Abheda Ekanta): The Samkhya school posits complete identity between causes and effects (e.g., primordial matter and its evolutes). Jainism argues that absolute identity would negate the distinctness of cause and effect.

- Refutation of Absolute Otherness and Unspeakability: The text refutes the Yogic view of absolute separateness and the Buddhist view of absolute unspeakability. Jainism posits a conditional (kathañchit) relationship of both difference and non-difference, and limited unspeakability.

- The Nature of Substance and Qualities: It explains that substance (dravya) and its modes (paryaya) are simultaneously identical and different, with different emphases (nayavada).

Chapter 5: Refutation of Ekantas of Relationality and Non-Relationality

- Relativity and Non-Relativity: The chapter discusses the Buddhist view that qualities (dharma) and the possessor of qualities (dharmi) are only relatively existent. It then critiques the Yogic view of absolute non-relationality.

- The Coexistence of Self-Existence and Relativity: Jainism asserts that qualities and their possessors are partially self-existent and partially relative.

Chapter 6: Refutation of Ekantika Hetuvada (Exclusive Reliance on Logic) and Agamavada (Exclusive Reliance on Scripture)

- The Role of Logic: Buddhists argue that all truths are proven by logic (hetu) alone, not by perception or scripture. Jainism counters that an exclusive reliance on logic would invalidate perception and scripture itself.

- The Role of Scripture: Vedantins prioritize scripture (agama), claiming that even logical conclusions are invalid if they contradict scripture. Jainism argues that scriptural validity itself relies on logic and the authority of the speaker (apta).

- The Role of Perception and Inference: Vaisheshikas and Sugatas (Buddhists) rely solely on perception and inference, rejecting scripture. Jainism argues that all means of knowledge (pramana), including scripture, are necessary for understanding reality.

- The Definition of an Authentic Speaker (Apta): The text defines an apta as one whose words are unfailing and consistent with logic and scripture.

- The Authority of Vedas: It refutes the apaurusheyata (non-human origin) of the Vedas, drawing parallels between Vedic and Jinendra's teachings, while highlighting the superior purity and efficacy of the latter.

- The Origin of Mantras: Jainism asserts that mantras originate from Jinendra's words, not from other sources.

Chapter 7: Refutation of Internal and External Ekantas

- The Buddhist Ideal of Pure Consciousness: The Vijnanadvaitavada (Buddhist school of consciousness-only) posits that only consciousness (vijnana) is real, while external objects are mere mental constructs. Jainism argues that this leads to the denial of proof and scripture.

- The Reality of External Objects: It contends that external objects are real and that our knowledge and language are dependent on them. The existence of external objects is proven by the possibility of both correct and incorrect perceptions.

- The Existence of the Soul (Jiva): The chapter refutes the Charvaka belief that the soul is merely the body and the Buddhist denial of an eternal soul. It establishes the soul's existence based on concepts like rebirth and continuity of consciousness, even amidst constant change.

- The Nature of Consciousness: It addresses the Samkhya view of the soul as unchanging and the Yoga view of it as unknowable through self-awareness.

- The Problem of Maya (Illusion): The text critiques the Advaita concept of the world being a manifestation of Maya.

Chapter 8: Refutation of Ekantas of Destiny and Effort

- Destiny vs. Effort: The chapter discusses the conflict between believing in destiny (bhagya) alone and believing in effort (purushartha) alone. It refutes the strict adherence to either.

- The Interplay of Destiny and Effort: Jainism advocates for an understanding of both destiny and effort as interdependent factors in causation.

Chapter 9: Refutation of Ekantas of Merit (Punya) and Demerit (Papa)

- The Causes of Merit and Demerit: It critiques simplistic views that identify causing suffering in others as sin and causing happiness as merit. Jainism emphasizes purity of mind (vishuddhi) and defilement (samklesha) as the true causes of karmic bondage.

- The Nature of Purity and Defilement: The chapter defines purity (vishuddhi) as religious and pure meditation (dharma and shukla dhyana) and defilement (samklesha) as agonized and wrathful meditation (arta and raudra dhyana).

Chapter 10: Refutation of Ekantas of Ignorance and Knowledge

- Ignorance and Bondage, Knowledge and Liberation: It refutes the exclusive claims that ignorance (avidya) causes bondage (bandha) and knowledge (vidya) leads to liberation (moksha). Jainism argues that liberation is achieved by the absence of deluding karma (moha), not merely by knowledge itself.

- The Role of Mixed Knowledge: It explains that while ignorance coupled with attachment causes bondage, even knowledge devoid of attachment can lead to liberation.

- The Nature of Karma: It refutes the Naiyayika view of karma as a quality of the soul, asserting it as material (pudgalika).

- The Creator God: The text refutes the Naiyayika concept of an Ishvara (God) as the creator of the universe, asserting the universe's beginningless nature.

- The Problem of Divine Intention: It questions why an intelligent God would create a flawed universe.

- The Nature of Potentiality and Impossibility (Bhavyatva and Abhavvyatva): It defines the concepts of potentiality and impossibility.

- The Nature of Proof: The chapter concludes by discussing the nature of proof (pramana) and the validity of memory (smriti), recognition (pratyabhijna), and logic (tarka) as independent means of knowledge. It clarifies the distinction between valid knowledge and fallacious knowledge.

- The Nature of Syadvada: It explains Syadvada as the ultimate principle for understanding reality, encompassing various perspectives.

- The Difference Between Syadvada and Kevala Jnana: It clarifies the distinction between Syadvada (conditionally true statements) and omniscience (kevala jnana).

- The Nature of Nayas: It defines the concept of nayas (standpoints) and differentiates between valid and invalid nayas.

- The Ultimate Nature of Reality: It concludes by quoting Acharya Samantabhadra on the nature of reality.

- The Function of Statements: It emphasizes that statements can convey truth through affirmation or negation, and that Syadvada is the hallmark of truth.

- The Fruit of the Text: The Acharyas outline the ultimate benefit of studying this text.

Key Figures:

The text prominently features the contributions of:

- Acharya Uma Swami: His Tattvartha Sutra provides the foundation.

- Acharya Samantabhadra: His Aptamimamsa (Devagama Stotra) is the primary text commented upon.

- Acharya Akalanka Deva: His Ashtashati (commentary) is considered complex and brilliant.

- Acharya Vidyananda Suri: His Ashtasahastri is the main commentary being discussed.

- Aryika Gyanmati Mataji: Her Hindi commentary, "Syadvad Chintamani," makes the profound philosophical arguments of Ashtasahastri accessible.

Significance:

Ashtasahastri Part 3, with Aryika Gyanmati Mataji's commentary, is presented as an invaluable resource for understanding the nuances of Jain logic and philosophy. It highlights the Jain commitment to refuting one-sided views and establishing a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of reality through the principles of Anekantavada and Syadvada. The text emphasizes the importance of rigorous logical analysis and scriptural authority in the pursuit of truth.