Ashtakprakaranam

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Ashtakprakaranam" by Haribhadrasuri, based on the provided pages:

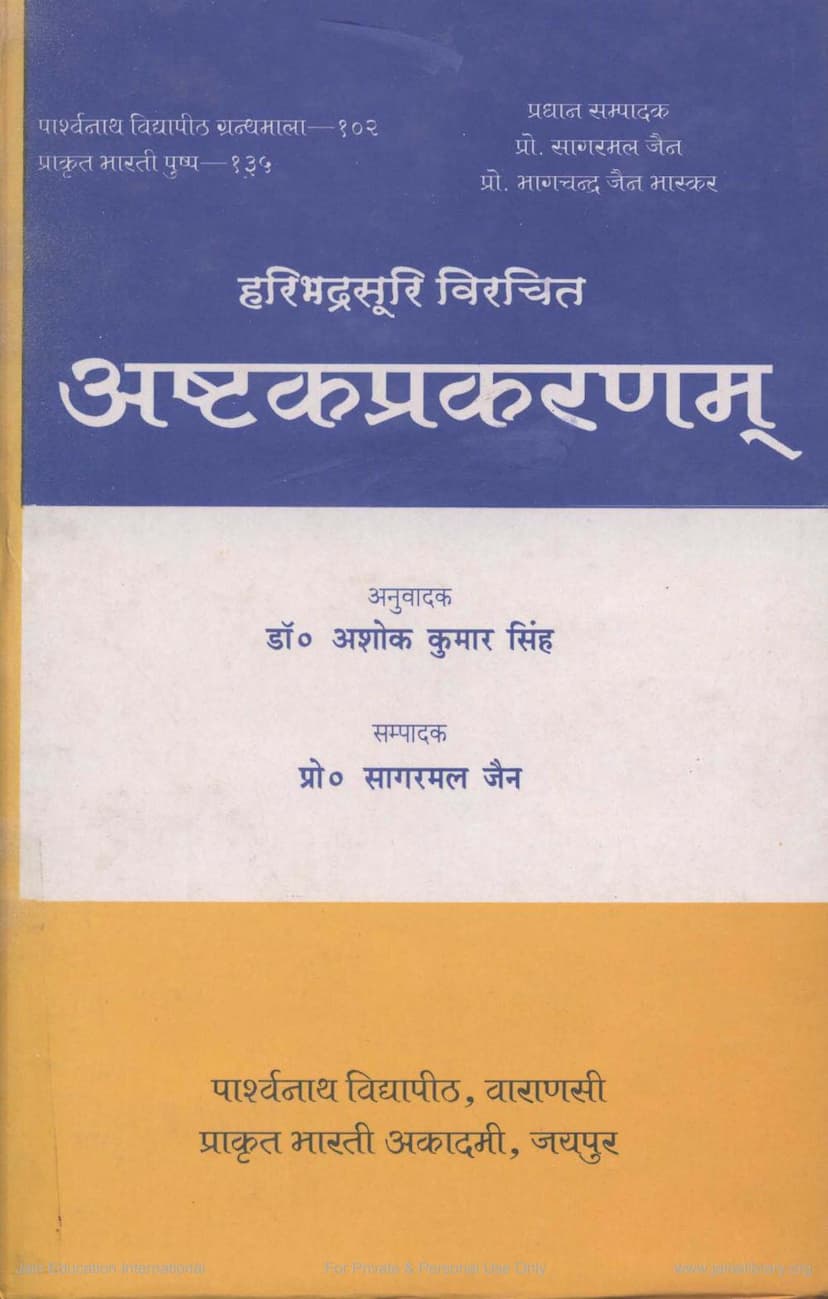

Book Title: Ashtakprakaranam Author: Haribhadrasuri Publisher: Parshwanath Vidyapith (in collaboration with Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur) Year of Publication: 2000 (First Edition) Translator: Dr. Ashok Kumar Singh Editor: Prof. Sagarmal Jain

Overall Purpose and Structure:

The Ashtakprakaranam is a significant work by the prominent Jain Ācārya Haribhadrasuri. The book, composed in Sanskrit, is a collection of 32 chapters (prakaranas), each typically containing eight verses (hence the title Ashtak, meaning eight). The final chapter has ten verses. The text aims to present the practical aspects of Jainism, clarify its importance, and point towards its ultimate spiritual essence. Haribhadrasuri, a brilliant scholar with profound knowledge of both Brahmanical and Jain traditions, uses this work to refute the objections of opponents (from other philosophical schools) and establish Jain doctrines based on scriptural authority.

Key Themes and Content Breakdown:

The book covers a wide range of topics related to Jain philosophy, ethics, and conduct. Here's a summary of the key themes explored in the individual ashtakas (chapters):

- Mahadevāṣṭakam: This chapter venerates the supreme being, identified as the first Tirthankara, Rishabhanatha, referred to as "Mahadeva." He is described as Vitaraga (free from passions), Omniscient, possessing eternal bliss, beyond karmic bondage, worshipped by all deities, and the creator of all ethical principles. The true worship of Mahadeva is through the practice of his teachings.

- Snānāṣṭakam: Discusses the concept of bathing, differentiating between physical (dravya) and spiritual (bhava) bathing. While physical bathing is considered a momentary purification of the body and a means to spiritual bathing for householders, monks are exhorted to focus on spiritual bathing through meditation.

- Pūjāṣṭakam: Explains two types of worship: impure (dravya puja) performed with material offerings like flowers, which leads to heaven and auspicious bondage, and pure (bhava puja) performed with eight virtues (non-violence, truth, non-stealing, celibacy, non-possession, guru-bhakti, penance, and knowledge) as 'flowers.' This pure worship leads to the purification of the soul and ultimately to liberation.

- Agnikārikāṣṭakam: Advises initiated monks to perform spiritual fire rituals using karma as fuel, auspicious thoughts as oblations, and meditation on Dharma as the fire. It emphasizes that initiation is for liberation, and liberation is the fruit of knowledge and meditation. It refutes the idea that external rituals or charity can eliminate sin, asserting that only penance can.

- Bhikṣāṣṭakam: Categorizes begging into three types:

- Sarvasampatkarī: The ideal begging by a detached monk for the welfare of elders, the weak, and the householder's family, leading to worldly and spiritual prosperity.

- Pauruṣaghni: The begging of a pseudo-monk who acts against monastic principles, solely for his livelihood, which is considered degrading.

- Vṛttibhikṣā: Begging by the poor, blind, and crippled for survival, considered better than Pauruṣaghni but not as good as Sarvasampatkarī.

- Sarvasampatkarībhikṣāṣṭakam: Refutes the argument that pure begging is impractical. Haribhadra establishes the feasibility of pure food, thereby indirectly validating the attainment of omniscience.

- Pracchannabhojanāṣṭakam: Advocates for monks taking food in private to avoid both binding merit (by giving to beggars) and generating ill-will towards the Jina-order (by denying them).

- Pratyākhyānāṣṭakam: Differentiates between material (dravya) and spiritual (bhava) renunciation. Material renunciation is associated with worldly desires and is considered flawed. Spiritual renunciation, free from worldly aspirations and performed with right conduct, is the means to liberation.

- Jñānāṣṭakam: Describes three types of knowledge: objective perception (subject to sensory limitations), subjective self-reflection (prone to delusion), and the ultimate realization of reality (which leads to liberation). True knowledge is detached and leads to liberation.

- Vairāgyāṣṭakam: Outlines three types of renunciation: mournful (leading to despair), delusion-infected (due to false beliefs), and genuine renunciation born from right knowledge, recognizing the suffering inherent in the cycle of birth and death.

- Tapo'ṣṭakam: Refutes the notion that austerity is inherently painful. It argues that suffering is caused by karma, not penance. True austerity is beneficial, leading to knowledge and peace, and is a natural consequence of spiritual progress.

- Vādāṣṭakam: Categorizes debates into three types: meaningless (with the arrogant), disputation (with trickery), and righteous debate (with the wise and impartial). Righteous debate is encouraged for spiritual growth.

- Dharmavādāṣṭakam: Defines righteous debate as one focused on virtues beneficial for liberation and relevant to one's philosophical system. It emphasizes reflecting on the truth of reality rather than the definitions of logic or epistemology.

- Ekāntanityapakṣakhandanāṣṭakam: Critiques the doctrine of an absolutely eternal and unchanging soul, arguing that it negates concepts like non-violence and moral conduct.

- Ekāntānityapakṣakhandanāṣṭakam: Refutes the doctrine of an absolutely impermanent soul, arguing that it also leads to inconsistencies in ethical principles.

- Nityānityapakṣamaṇḍanāṣṭakam: Proposes that the soul is both permanent and impermanent, and exists in relation to the body, which allows for the occurrence of actions like violence and non-violence.

- Māṁsabhakṣaṇadūṣaṇāṣṭakam: Critiques the idea that meat-eating is not sinful, using scriptural arguments (including from Manusmriti and Lankavatara Sutra) to demonstrate its inherent flaws and prohibitions.

- Māṁsabhakṣaṇadūṣaṇāṣṭakam: Continues the refutation of meat-eating, highlighting contradictions within scriptural arguments and emphasizing that the avoidance of meat is the path to great rewards.

- Madyapānadūṣaṇāṣṭakam: Denounces the consumption of alcohol, describing it as a cause of delusion and a mine of sins, citing the example of a sage who fell due to its consumption.

- Maithunadūṣaṇāṣṭakam: Refutes the idea that sexual intercourse is without sin, linking it to attachment and the destruction of the soul. It cites scriptural examples and analogies to illustrate its harmful nature.

- Sūkṣmabuddhyāśrayaņāṣṭakam: Advises careful examination of vows and intentions, as ill-considered good intentions can lead to harm. It stresses the importance of understanding the spirit of the law and acting with impartiality.

- Bhāvavisuddhivicārāṣṭakam: Explains that purity of mind (bhāva śuddhi) is achieved through detachment from passions like attachment, hatred, and delusion, and by adhering to the teachings of the enlightened and the canons.

- Śāsanamālinyaniṣedhāṣṭakam: Emphasizes the importance of upholding the Jaina tradition (Shasan) and avoiding its defamation, which leads to spiritual downfall. Promoting the tradition leads to spiritual upliftment and liberation.

- Puṇyānubandhipuṇyādivivaraņāṣṭakam: Explains how virtuous actions lead to better births and spiritual progress. Purity of mind, achieved through obedience to elders and adherence to canons, is crucial for binding auspicious karma.

- Puṇyānubandhipuṇyapradhānaphalāṣṭakam: Highlights that virtuous conduct, including service to parents and gurus, is not an obstacle to spiritual progress but rather leads to excellent results, even Tirthankarahood.

- Tīrthakrddānamahattvasiddhyaṣṭakam: Addresses the argument that the charity of Tirthankaras is not "great" because it is quantifiable. Haribhadra argues that its greatness lies in its purpose – to eradicate the need for alms seekers and in the compassionate declaration to give freely.

- Tīrthakrddānanisphalatāparihārāṣṭakam: Refutes the claim that Tirthankaras' charity is futile because they achieve liberation in one lifetime. It states that charity is a manifestation of compassion and helps in shedding karma.

- Rājyādidāne'pi-tirthakṛto-doṣabhāvapratipādanāṣṭakam: Defends the practice of Tirthankaras renouncing kingdoms and engaging in activities like marriage or crafts. It argues that these actions are done for the welfare of the world and to maintain social order, and are not sinful when performed with the right intention and for the greater good.

- Sāmāyikasvarūpanirūpaņāṣṭakam: Defines equanimity (Samayika) as a means to liberation, comparing it to the purifying fragrance of sandalwood. It contrasts true equanimity with worldly magnanimity and discusses the concept of Bodhisattvas.

- Kevalajñānāṣṭakam: Describes Omniscience (Kevala Jnana) as the intrinsic nature of the soul, obscured by karma. It explains that this knowledge, when attained through pure conduct, illuminates the universe and the non-universe. It also clarifies the analogy of moonlight with Omniscience.

- Tīrthakṛddeśanāṣṭakam: Explains why Tirthankaras, despite being detached, engage in preaching. It attributes this to the accumulation of Tirthankara-naming karma and the desire for the welfare of all beings. The power of their words and the potential of the audience are also discussed.

- Mokṣāṣṭakam: Defines liberation as the complete destruction of karma, leading to a state of eternal bliss, free from suffering and worldly existence. It refutes the argument that bliss is impossible without physical enjoyment and describes the ultimate bliss of liberation.

Significance and Contribution:

The Ashtakprakaranam is a valuable compendium that showcases Haribhadrasuri's erudition and his ability to synthesize complex Jain doctrines with logical reasoning. By drawing upon and referencing various ancient texts from different traditions, he effectively clarifies and defends Jain teachings, making them accessible and persuasive. The book serves as a guide for both monks and laypeople, promoting righteous conduct, intellectual inquiry, and spiritual aspiration. The translation by Dr. Ashok Kumar Singh, along with the editorial work by Prof. Sagarmal Jain, makes this important text available to a wider audience.