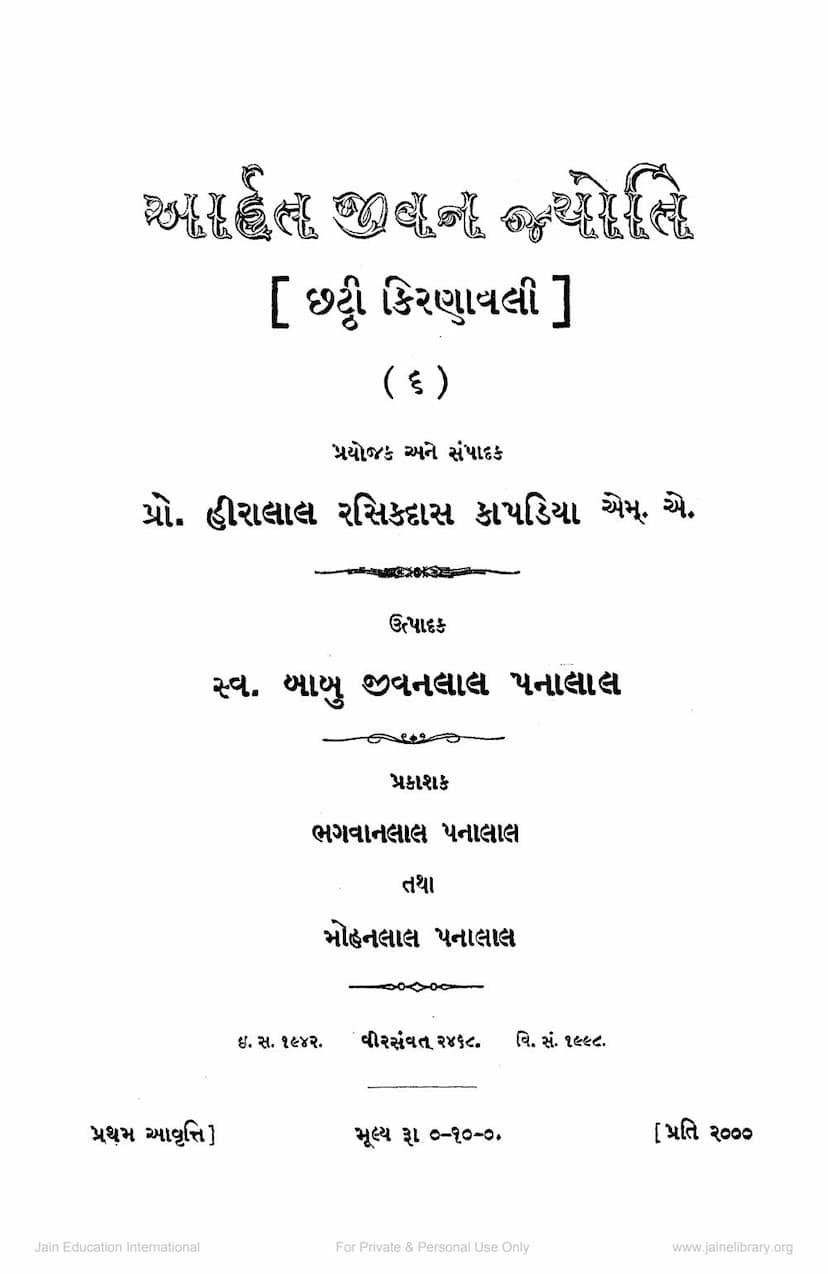

Arhat Jivan Jyoti

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Arhat Jivan Jyoti," based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Arhat Jivan Jyoti (The Life-Light of the Arhat) Author: Hiralal R Kapadia Publisher: Bhagwanlal Pannalal Overall Purpose: This book appears to be a religious educational text designed to impart Jain principles and teachings to students, progressing from basic to advanced levels. The structure uses "Kiran" (rays) to present different topics.

Key Information from the Initial Pages (Pages 1-11):

- Publication Details: The book is a first edition published in 1942 (Vir Samvat 2468, V. Samvat 1998). It is dedicated to the memory of the parents of the publishers, Bhagwanlal Pannalal and Mohanlal Pannalal, who initiated the series in memory of their late brother, Babu Jivanlal Pannalal.

- Editorial Vision: Professor Hiralal Rasikdas Kapadia M.A. is the planner and editor. The aim was to create eleven "Kiranavali" (series of rays) to benefit students with Gujarati literacy and progressively higher levels of understanding. The first four Kiranalis were published by the late Babu Jivanlal Pannalal, and this sixth Kiranavali is being released by his brothers, who are continuing his work.

- Community Involvement: The publishers sent the draft of this Kiranavali to various scholars, school administrators, and Jain and non-Jain gentlemen for feedback and suggestions, expressing gratitude for their input. They also acknowledge reviewers in newspapers.

- Educational Adoption: The first five Kiranalis are being used as textbooks for religious studies in Babu Pannalal P. Jain High School and other schools, and are also used as prizes.

- Content Structure: The book is divided into "Kirans" (chapters or rays), covering various Jain philosophical and doctrinal topics. The table of contents (Pages 5-8) lists 40 Kirans, covering subjects like the path to liberation, the nature of the soul, karma, the structure of the universe, the lives of spiritual exemplars, and Jain rituals.

- Kiran 1: Moksha ka Marg (The Path to Liberation): This Kiran likens the spiritual journey to a lost person finding their way home. It emphasizes the need to know the path to Moksha (liberation) by finding those with true knowledge. It introduces the core Jain concepts of Samyagdarshan (Right Faith/Belief), Samyagjnana (Right Knowledge), and Samyakcharitra (Right Conduct) as the means to achieve this, leading to victory over passion and attainment of the state of liberation (Moksha). It also touches upon the fourteen stages of spiritual progress (Gunsthan).

- Kiran 2: Nirjara (Shedding of Karma): This Kiran discusses the two types of souls: liberated (Mukta) and worldly (Sansari). It explains that worldly souls are bound by karma. Karma separates from the soul either when its fruits are experienced naturally or when it is shed prematurely through practices like penance (Tapas). These two types of shedding are called Akama-Nirjara (unintentional shedding) and Sakaama-Nirjara (intentional shedding). The analogy of ripening mangoes is used to illustrate this concept.

- Kiran 3: Vichitra Kathano (Peculiar Narratives): This Kiran recounts an incident involving Lord Mahavir Swami, King Shrenik, Abhaykumar, and Kalak Suri the butcher. A deity arrives and makes seemingly contradictory statements to each, such as wishing Mahavir to die (to attain liberation), Shrenik to live (as he's destined for hell), and Abhaykumar to either live or die (as he will do good in life and go to heaven in death). The meaning behind these statements reveals the ultimate spiritual consequences of actions.

- Kiran 4: Mudra (Gestures/Posture): This Kiran discusses the use of specific hand gestures or postures (Mudra) in Jain worship, particularly during Chaitra Vandan. It describes three Mudras: Yogamudra (lotus-like joining of hands on the stomach), Jinmudra (the posture of the Jina standing with feet apart, hands hanging), and Muktanmuktimudra (hands joined like a lotus bud near the forehead).

- Kiran 5: Lok ka Swarup (The Nature of the Universe): This Kiran explains the Jain cosmology. It states that Akash (space) is an infinite, immeasurable substance. The universe (Loka) occupies a portion of Akash, while the rest is Aloka (non-universe). Loka is divided into three parts: Adholok (lower world), Madhyam Lok (middle world), and Urdhva Lok (upper world). It provides dimensions and shapes for these regions, comparing the overall Loka to an inverted pot with a rim and a mridanga on top. It also introduces the concept of "Rajjus" as a unit of measurement for the universe.

- Kiran 6: Das Prana (Ten Vitalities/Life-Forces): This Kiran defines "Prana" beyond just breath. It enumerates ten Pranas: the five senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch), the mind (Manobal), speech (Vachanbal), body strength (Kayabal), breath (Uchchwas-Nihchwas), and lifespan (Ayushya). It explains how different life forms possess a varying number of these Pranas, from a minimum of four for one-sensed beings to ten for some five-sensed beings with a mind.

- Kiran 7: Jambudvipa: This Kiran focuses on the continent of Jambudvipa, located in the Madhyam Lok. It describes its disc-like shape, the central Meru mountain, and its seven divisions called Kshetra, Vamsha, or Varsha. It names these as Bharatakshetra (where we reside) and six others (Haimavat, Hari, Videha, Ramyaka, Hiranyavat, and Airavat), explaining how they are separated by six mountain ranges called Varshadharas.

- Kiran 8: Veeron ne (To the Heroes): This is a poem encouraging listeners to follow the path of truth and righteousness, remembering the teachings of the Jinas (heroes). It emphasizes understanding the principles of Svadavada (relativism) and acting with dharma in mind.

- Kiran 9: Dharma, Adharma, and Akash (Substance of Motion, Rest, and Space): This Kiran defines the non-living (Ajiva) substances as Pudgal (matter), Dharmastikaya (substance of motion), Adharmastikaya (substance of rest), Akash (space), and Kala (time). It clarifies that Dharma and Adharma are not synonyms for merit or demerit but are the principles that help substances move or remain at rest, respectively. Space is defined as that which provides room for all other substances.

- Kiran 10: Panch Astikaya (Five Existences/Substances): This Kiran explains the five fundamental categories of existence in Jainism: Jiva (soul), Pudgal (matter), Dharmastikaya, Adharmastikaya, and Akashastikaya. It defines Astikaya as that which has "Pradesha" (spatial units) and forms a collection. Time (Kala) is not considered an Astikaya as it does not have Pradesha, or at most, only one Pradesha according to Digambaras.

- Kiran 11: Adhi Dvipa (Other Continents): This Kiran continues the description of the universe, detailing the arrangement of continents (Dvipa) and oceans, starting from Jambudvipa and Lavana Samudra. It describes Dhataki Khanda, Pushkara Dvipa, and subsequent oceans and continents, emphasizing that the size doubles with each subsequent continent. It introduces the concept of Manushyottara Mountain, which divides Pushkara Dvipa into two halves and marks the boundary of the human realm (Manushyaloka). It explains the division of Dhataki Khanda and the Pushkara Dvipa half into eastern and western halves. The concept of "Adhai Dvipa" (two and a half continents) comprising Jambudvipa, Dhataki Khanda, and half of Pushkara Dvipa, along with their surrounding oceans, is highlighted as the human world.

- Kiran 12: Vandan Vyavahar (Etiquette of Salutation): This Kiran discusses various forms of greeting and salutations in different cultures and religions, contrasting them with Jain greetings. It highlights how Jains greet each other with "Juhar" (a respectful bow). It details the nuances of greeting monks, including "Phentavandan" (bowing the head) and "Thobh Vandan" (Panchanga Pranam – touching knees, elbows, and forehead to the ground), and the blessings given by monks ("Dharmalabh"). It also explains the concept of "Dvadashavarta Vandan" (salutation with twelve repetitions) and mentions how Jains communicate through letters, using terms like "Jaya Jinendra" and "Vandan."

- Kiran 13: Karmabhumi aur Akarmabhumi (Action and Non-Action Lands): This Kiran differentiates between Karmabhumi (lands where Tirthankaras are born and where humans actively strive for spiritual liberation) and Akarmabhumi (lands of enjoyment where spiritual effort is not the primary focus). It lists fifteen Karmabhumi in the human realm (five Bharat, five Airavat, and five Mahavideha). It also explains that within the Mahavideha regions, Devakuru and Uttarukuru are considered Akarmabhumi because of the "Yuglik Dharma" (a state of communal living and procreation), which doesn't allow for the strict asceticism needed for Tirthankarahood. It defines "Chakravarti," "Ardhachakravarti" (Vasudev), and "Prativasudev" and lists the "Shalaka Purushas" (eminent individuals) born in each cycle.

- Kiran 14: Gyan ke Paanch Prakar (Five Types of Knowledge): This Kiran elaborates on the five types of Jain knowledge: Matijnana (sensory knowledge), Shrutajnana (scriptural knowledge), Avadhijnana (clairvoyance), Manahparyayajnana (telepathy), and Kevalajnana (omniscience). It explains that the first two require senses and mind, while the latter three are direct and do not depend on external means. It distinguishes between those who have partial direct knowledge (Chhadmasthas) and the omniscient (Kevalis).

- Kiran 15: Chyavan-Kalyanak (The Conception Ceremony): This Kiran describes the conception of a Tirthankara. It explains that Tirthankaras are typically born in the celestial realm in their previous life and descend to human mothers' wombs. The act of conception is called Chyavan-Kalyanak. During this event, a period of suffering is alleviated in the three worlds, and a radiant light spreads. The mother experiences fourteen auspicious dreams, such as an elephant, lion, lotus, moon, and sun. The seats of the 64 Indras tremble at this auspicious event.

- Kiran 16: Dwadashangi Bhag 1 (Twelve Limbs of Scripture - Part 1): This Kiran introduces the concept of the Dwadashangi (the twelve principal divisions of Jain scripture). It explains that each Tirthankara's chief disciple (Ganadhar) compiled these limbs. It highlights the teachings of Lord Mahavir Swami and his eleven Ganadhars, particularly the first Ganadhar, Indrabhuti, who received key philosophical insights ("Nishadh-atray" and "Tripadi") from Mahavir, leading to the compilation of the Dwadashangi. The core concept of "existence, origin, and permanence" (Udyam-Vyaya-Dhruvya) is presented as a fundamental key.

- Kiran 17: Dwadashangi Bhag 2 (Twelve Limbs of Scripture - Part 2): This Kiran continues the discussion on the Dwadashangi, listing the names of the twelve Angas in Prakrit and Sanskrit. It emphasizes Drishtivada as the most important Anga, and within that, Purvachara (Purva) as the most significant section, whose scholars are called Shrutakevalis. It briefly describes the content of some Angas, such as Acharanga (monastic conduct), Suyagada (philosophical views of other sects), Thana (enumerations), Samavaya (classification), Vivahapanutti (discussions on various topics), Jnatadharmakatha (religious stories), Upasakadasha (duties of lay followers), Antakrida, Anuttaraupapatikadasha (celestial beings), Prakirnak, Vipakashruta (fruits of karma), and Drishtivada.

- Kiran 18: Arya and Lechha (Civilized and Barbarian/Outsiders): This Kiran categorizes humans into two main groups: Arya (civilized) and Lechha (outsiders/uncivilized). It further divides Aryas based on six criteria: region (Kshetra), lineage (Jati), family (Kula), occupation (Karma), craft (Shilpa), and language (Bhasha), leading to six types of Aryas. Those who do not fit these criteria are considered Lechhas.

- Kiran 19: Shri Bhadrabahuswami Part 1: This Kiran narrates the lineage of Jain monks after Lord Mahavir, focusing on the disciples of Shri Sudharmaswami, and eventually reaching Shri Bhadrabahuswami. It highlights the significant event of a severe famine causing the loss of the twelfth Anga of the scripture, and Bhadrabahuswami's role in re-teaching it after undergoing a profound meditation. It also mentions the challenges faced in transmission and the strict rules governing discipleship.

- Kiran 20: Shri Bhadrabahuswami Part 2: This Kiran continues the story of Bhadrabahuswami and his disciple Sthulabhadra. It details Sthulabhadra's initial difficulty in fully absorbing the teachings, his miraculous display of power, and Bhadrabahuswami's subsequent decision to modify the teaching approach due to a perceived decline in human mental capacity over time. It also mentions Bhadrabahuswami's commentaries and the contributions of Sthulabhadra as the last Shrutakevali in terms of scriptural wording.

- Kiran 21: Kaal ke Vibhag (Divisions of Time): This Kiran explains the Jain concept of time, starting with the smallest unit, "Samaya." It defines "Avalika" and "Muhurta," and then provides a chronological breakdown of units like Uchchwas, Nishchwas, Stoka, Lava, Ghadi, Muhurta, Ahoratra, Paksha, Masa, Ritu, Ayana, Samvatsara, and Yuga. It introduces larger time cycles like "Purvag" and "Shirsaprahelika" as measures of immense periods. It also touches upon the nature of "Antarmuhurta" (a period less than a Muhurta).

- Kiran 22: Punnya aur Paap ke Prakar (Types of Merit and Demerit): This Kiran categorizes karma into four types based on their outcomes: Punyanubandhi Punnya (merit leading to further merit), Papanubandhi Punnya (merit leading to demerit), Punyanubandhi Papa (demerit leading to merit), and Papanubandhi Papa (demerit leading to further demerit). It explains how these karmic combinations influence an individual's happiness or suffering in this life and the next, often leading to seemingly paradoxical situations where "bad" people appear happy and "good" people appear unhappy.

- Kiran 23: Upadhan Bhag 1 (Upadhana Part 1): This Kiran describes the Jain ritual of "Upadhana," which is a form of penance and study. It explains that to be considered a true Jain, one must undergo Upadhana and receive a "mala" (garland) in a ceremony. Upadhana involves systematically studying specific sacred texts or mantras under the guidance of a guru. It outlines six types of Upadhana with their associated fasting periods and rituals.

- Kiran 24: Upadhan Bhag 2 (Upadhana Part 2): This Kiran continues the explanation of Upadhana, detailing the number of "Vachanas" (recitations/lessons) associated with each of the six Upadhanas. It specifies the number of fasts and the specific texts or mantras to be studied. It also lists several daily practices that are part of the Upadhana discipline, such as performing Pratikraman, observing Poushadh Vrata, performing Devavandana, and reciting specific mantras like Navkar.

- Kiran 25: Karma ki Uttar Pravrittiyan Part 1 (Sub-types of Karma Part 1): This Kiran delves into the "Uttar Pravrittiyan" (sub-types) of the eight main karmas. It details the five sub-types of Jnanavaraniya Karma (knowledge-obscuring karma) and the nine sub-types of Darshanavaraniya Karma (perception-obscuring karma), including sleep-related states. It also briefly explains the two sub-types of Vedaniya Karma (feeling karma) and the classification of Mohaniya Karma (delusion-causing karma) into Darshan Mohaniya (3 sub-types) and Charitra Mohaniya (25 sub-types).

- Kiran 26: Karma ki Uttar Pravrittiyan Part 2 (Sub-types of Karma Part 2): This Kiran continues the discussion on karmic sub-types, detailing the four sub-types of Ayushya Karma (lifespan karma: celestial, human, animal, and hellish). It then lists 42 sub-types of Namakarma (name-karma), categorizing them by their influence on physical attributes like color, smell, taste, touch, voice, beauty, and reputation. It also explains the two sub-types of Gotra Karma (lineage karma: high and low lineage) and the five sub-types of Antaraya Karma (obstruction karma: donation, gain, enjoyment, prolonged enjoyment, and energy).

- Kiran 27: Meru Parvat (Mount Meru): This Kiran provides a detailed description of Mount Meru, a central cosmic mountain in Jain cosmology. It mentions its immense height (100,000 yojanas), its division into three parts extending into the lower, middle, and upper worlds, and its association with four divine groves (Bhadrasal, Nandan, Saumanas, and Panduk). It also describes the "Chulika" at the summit and mentions that there are five Meru mountains in total across the continents. It explains how Tirthankaras are consecrated on specific platforms on these mountains based on their birth location.

- Kiran 28: Manushya Bhav aur uski Durlobhta Bhag 1 (Human Life and its Rarity Part 1): This Kiran emphasizes the extreme rarity of obtaining a human birth, which is considered more valuable than a celestial birth because it offers the best opportunity for spiritual progress and liberation. It illustrates this rarity using ten analogies involving food, dice, grain, gambling, treasures, dreams, chakras, leather, yokes, and atoms, each depicting an extremely difficult or improbable scenario to highlight the preciousness of human life.

- Kiran 29: Manushya Bhav aur uski Durlobhta Bhag 2 (Human Life and its Rarity Part 2): This Kiran continues the theme of the rarity of human birth by providing further analogies. It uses examples of dreams, a target-shooting contest involving multiple obstacles, a vast lake covered in algae with a rare opening, and the improbable joining of a needle and a yoke in a vast ocean, all to underscore the difficulty of obtaining a human rebirth.

- Kiran 30: Syanaguddhi ke Udaharan (Examples of Sleep-Walking Karma): This Kiran explains the phenomenon of "Syanaguddhi" (sleep-walking) caused by specific karmic effects. It provides two examples of monks who, due to the rise of this karma, performed actions unconsciously at night, which they mistook for dreams. The gurus recognized the karmic influence and took appropriate action.

- Kiran 31: Char Nikay ke Devo Bhag 1 (Four Classes of Celestial Beings Part 1): This Kiran classifies celestial beings (Devas) into four categories (Nikayas): Bhavanapati (dwellers in mansions), Vyantar (intermediate beings), Jyotishka (luminous beings), and Vaimanika (celestial palace dwellers). It details the Bhavanapati and Vyantar Devas, describing their ten and eight types, respectively, and their subdivisions like Indra, Samanika, etc. It also mentions their dwelling places and specific attributes.

- Kiran 32: Char Nikay ke Devo Bhag 2 (Four Classes of Celestial Beings Part 2): This Kiran continues the description of celestial beings, focusing on the Jyotishka and Vaimanika Devas. It explains that Jyotishka Devas (Sun, Moon, planets, stars) are luminous and are responsible for the division of time. It details their positions and relative altitudes around Mount Meru. It then categorizes Vaimanika Devas into Kalpopapanna (those residing in the twelve heavens) and Kalpatita (those beyond the heavens), further dividing the latter into Traivreyakas and Anuttaravasis. It highlights the unique qualities of Anuttara celestial beings who achieve liberation in their last life.

- Kiran 33: Janma Kalyanak (The Birth Ceremony): This Kiran describes the birth ceremony of a Tirthankara. It explains the astronomical and celestial events that occur, such as the trembling of the seats of celestial beings. It details the role of Dikumaris (virgin celestial attendants) and the 64 Indras in bathing and adorning the infant Tirthankara. The elaborate ritual of consecration on Mount Meru involving divine offerings and a large procession is described.

- Kiran 34: Diksha Kalyanak (The Renunciation Ceremony): This Kiran describes the renunciation ceremony of a Tirthankara. It begins with the Tirthankara's decision to renounce worldly life after being invited by Lokantika Devas to establish the religious order. It details the year-long "Samvatsarik Dana" (annual charity) performed before renunciation, where anything desired could be taken. It then describes the Tirthankara's departure for the forest, the symbolic act of plucking out hair, and the attainment of Manahparyayajnana upon taking initiation. The divine celebrations, including the "five divine offerings" (Pancha Divyas), are also mentioned.

- Kiran 35: Samavasarana Bhag 1 (The Assembly Hall Part 1): This Kiran begins to describe the Samavasarana, the celestial assembly hall created by gods for Tirthankaras to deliver sermons. It details the meticulous construction process, starting with clearing the ground, sprinkling water, and building a tiered platform (Pithbandh) with staircases. It explains the creation of three concentric circular ramparts made of silver, gold, and jewels, each housing different categories of beings. It also mentions the presence of divine banners, umbrellas, and music.

- Kiran 36: Samavasarana Bhag 2 (The Assembly Hall Part 2): This Kiran continues the description of the Samavasarana, detailing the arrangement of the three ramparts (circular and square types), the dimensions of their walls, and the distances between them. It specifies the types of celestial beings guarding the gates of each rampart and the divine attendants (Pratiharnis) inside. It describes the Ashok tree (Chaitya Vriksha) under which the Tirthankara sits, the bejeweled throne, the three umbrellas, the chauris (fly-whisks), and the Dharma Chakra (wheel of dharma). It also explains the division of the audience into twelve groups (Parshadas) based on their spiritual status and the seating arrangements for each group.

- Kiran 37: Angara-mardika Acharya (Acharya Angara-mardika): This Kiran tells the story of Acharya Angara-mardika, an "Abhavya" (incapable of attaining liberation) who, despite outwardly adhering to strict asceticism, lacked true compassion. It illustrates this through an incident where his disciples, warned by a virtuous Acharya, observed Angara-mardika's hypocrisy in his actions, leading them to renounce him. The story highlights the importance of genuine adherence to Jain principles over mere outward appearances.

- Kiran 38: Aath Pravachanamata (Eight Mothers of the Teaching): This Kiran explains the concept of the "Eight Mothers of the Teaching," which are the five Samitis (careful conduct) and three Guptis (restraints). It defines Samiti as engaging in proper conduct and Gupti as abstaining from improper conduct, relating them to actions of body, speech, and mind. The five Samitis are Ischamiti (careful walking), Bhashasamiti (careful speech), Eschenasamiti (careful begging for alms), Adananikshepasamiti (careful handling of objects), and Utsargasamiti (careful disposal of waste). The three Guptis are Kayagupti (restraint of body), Vachanagupti (restraint of speech), and Managupti (restraint of mind). These eight are considered "mothers" because they give birth to, nurture, and purify conduct (Charitra).

- Kiran 39: Utsarpini and Avsarpini (Ascending and Descending Time Cycles): This Kiran explains the Jain concept of cosmic time cycles, stating that the universe is without beginning or end. It describes two cyclical phases: Utsarpini Kala (ascending time), where conditions gradually improve, and Avsarpini Kala (descending time), where conditions gradually deteriorate. These cycles are further divided into six periods called "Aras" or "Avas" (stages), each with distinct characteristics affecting lifespan, physique, happiness, and spiritual inclination. It notes that the current era in Bharat and Airavat Kshetras is the fifth stage of Avsarpini Kala.

- Kiran 40: Samanya Kevali ke Prakar (Types of Ordinary Omniscient Beings): This Kiran distinguishes between "Tirthankaras" and "Samanya Kevalis" (ordinary omniscient beings). While both possess Kevalajnana (omniscience), Tirthankaras have special qualities: superior past merit, seeing fourteen auspicious dreams at conception, being self-enlightened (Swayambuddhas), attaining Manahparyayajnana upon initiation, having five auspicious ceremonies celebrated by gods, possessing extraordinary physical beauty, and having speech that can be understood by all beings and can resolve all doubts. It also mentions different categories of Samanya Kevalis based on when they attained omniscience (e.g., "Mokevli" who only answer questions, "Antakruti Kevali" who attain omniscience near the end of their lives, and "Ashrutvakevali" who did not hear religious discourse in their current life).

Overall:

"Arhat Jivan Jyoti" is a comprehensive Jain religious education book. It systematically introduces fundamental Jain doctrines, cosmology, philosophy, and practices through a series of "rays" or chapters. The language is aimed at students, making complex concepts accessible. The inclusion of stories, analogies, and detailed explanations of rituals and celestial beings makes it an informative and engaging resource for understanding Jainism.