Aptamimansa

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Āptamīmāṁsā" by Acārya Samantabhadra, based on the provided text and catalog link:

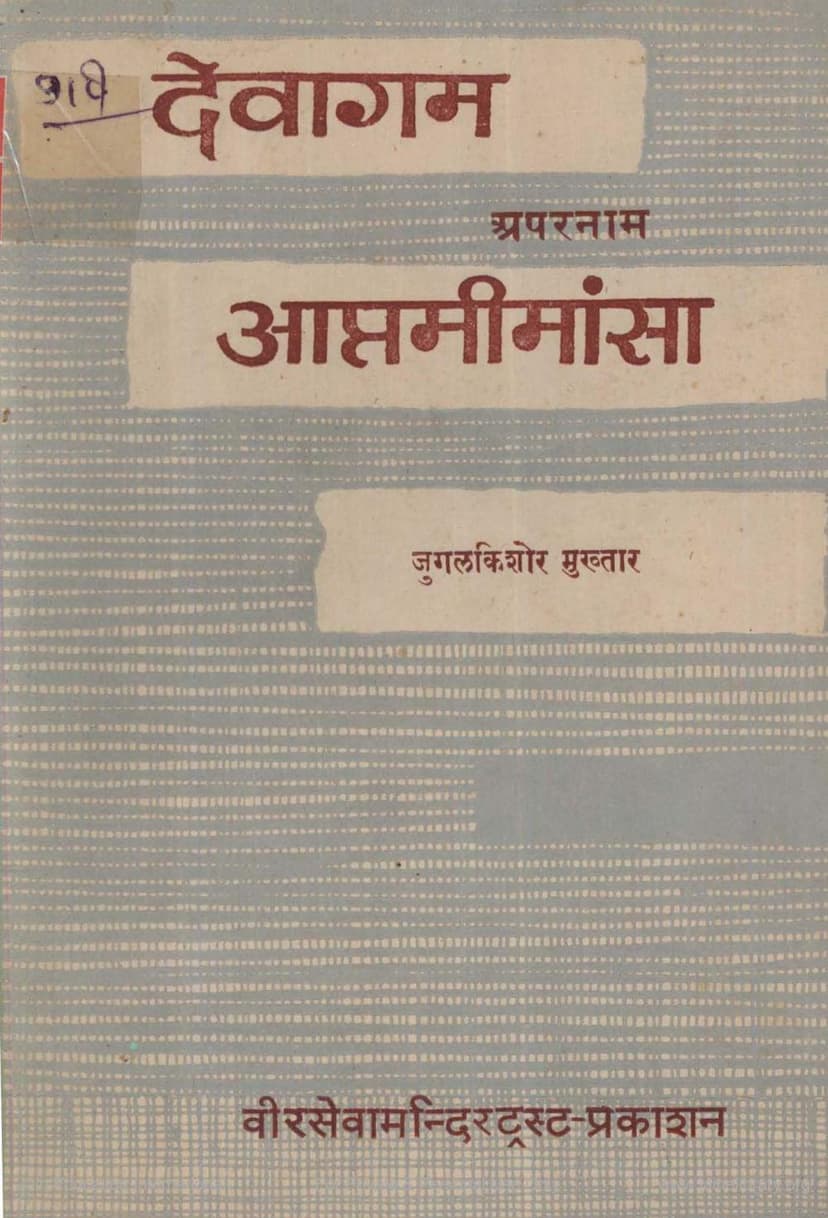

Book Title: Āptamīmāṁsā (also known as Devāgama) Author: Acārya Samantabhadra Translator/Commentator: Jugalkishor Mukhtar Publisher: Veer Seva Mandir Trust

Overview:

Āptamīmāṁsā, also referred to as Devāgama, is a seminal philosophical work by the revered Jain Acārya Samantabhadra. It is a profound exploration of the nature of the "Āpta" (the truly worthy, the omniscient beings, exemplified by the Jinas) and an elaborate critique of various philosophical viewpoints prevalent during his time. The book systematically analyzes and refutes one-sided or absolute (ekānta) doctrines across several key philosophical dichotomies, ultimately establishing the Jain perspective of "anekānta" (non-absolutism or manifoldness) as the most logical and comprehensive understanding of reality.

The text is structured into ten chapters (paricchedas), with a total of 114 verses (kārikās). The translation and commentary by Jugalkishor Mukhtar are highly valued for their clarity and depth in explaining the intricate philosophical arguments presented in the original Sanskrit.

Key Themes and Arguments:

The Āptamīmāṁsā functions as a defense and exposition of the Jain philosophical system by dissecting and dismantling opposing viewpoints. The core of the argument revolves around the principle of syādvāda (the doctrine of "perhaps" or "conditionally") and anekānta (non-absolutism). Acārya Samantabhadra argues that reality is complex and can only be understood through multiple perspectives.

Chapter-wise Summary of Arguments:

-

Chapter 1: Devāgamādi Vibhūtiyāṁ Āpta-Gurutvaṁ Na Hetuḥ (Venerable Attributes are Not the Basis for Defining an Āpta):

- Argues that external manifestations like divine arrival (devāgama), levitation (gagana-gamana), divine musical instruments (divya-dhvani), celestial umbrellas and attendants (chāmarādi-vibhūti), and even a perfect physical form (vigrahādi-mahodaya) are not definitive proofs of an Āpta.

- These attributes can be found in even ordinary beings or potentially in illusionists (māyāvīs).

- Similarly, the status of being a Tīrthaṁkara (founder of a spiritual lineage) is also not a sole criterion, as different tīrthaṁkaras have conflicting teachings, suggesting not all can be perfectly Āpta.

- True Āptatva comes from the complete eradication of defects and coverings (karmas and their obstructions).

- Omniscience (sarvajñatva) is established through inference – if someone can perceive subtle, distant, and past/future events (which are inferable), then they are omniscient.

- The true Āpta is identified as one whose speech is free from contradiction with logic and scripture, and whose teachings (anekānta) are not contradicted by valid perception (pramāṇa) or established doctrines (prasiddha).

- Criticizes those who reject Jain teachings, adhere strictly to one-sided views (ekānta), and claim to be Āptas without true understanding, as their claims are ultimately refuted by valid knowledge.

-

Chapter 2: Adwaita-Ekāntaṁ Sadōṣatā (The Fallacy of Absolute Monism):

- Critiques the doctrine of absolute monism (adwaita), which posits reality as a single, undifferentiated entity.

- Argues that monism cannot account for the observed distinctions in agents (kāraka), actions (kriyā), cause-effect relationships, duality of merit/demerit (puṇya-pāpa), knowledge/ignorance (vidyā-avidyā), bondage/liberation (bandha-mokṣa), etc.

- If monism is established through reasoning, it inherently implies duality between the reasoner and the reasoned. If argued without reason, then any dualistic claim could also be made.

- Highlights the self-contradictory nature of trying to negate duality (dvaita) to establish monism (adwaita).

-

Chapter 3: Nityatva-Ekāntaṁ Sadōṣatā (The Fallacy of Absolute Permanence/Eternalism):

- Critiques the doctrine of absolute permanence (nityatva), which denies any change or modification in reality.

- Argues that if things are absolutely permanent, then causality, agency, perception, and the fruits of action (karma) become impossible.

- The concept of transformation (vikriyā) is essential for understanding cause and effect, which is denied by eternalism.

- If the cause and effect are absolutely permanent, they cannot undergo change, rendering concepts like creation or action meaningless.

- Questions how phenomena like birth and death, bondage and liberation, merit and demerit can exist if everything is eternally unchanging.

-

Chapter 4: Kṣaṇika-Ekāntaṁ Sadōṣatā (The Fallacy of Absolute Momentariness/Impermanence):

- Critiques the doctrine of absolute momentariness (kṣaṇika), which posits that reality consists only of momentary, discrete units without any continuity.

- Argues that this view makes concepts like rebirth (pretyabhāva), causal relationships (hetu-phalabhāva), continuity of consciousness (saṁtāna), recognition (pratyabhijñā), memory (smaraṇa), and the very notion of "cause" and "effect" impossible.

- If there's no continuity, how can one action lead to a future result, or how can knowledge be accumulated or remembered?

- The denial of continuity leads to the denial of cause and effect, rendering all actions and their consequences meaningless.

-

Chapter 5: Apēkṣā-Anapēkṣā-Ekāntōṁ Sadōṣatā (The Fallacy of Absolute Relativity/Non-Relativity):

- Analyzes the doctrines concerning the dependence (apēkṣā) and independence (anapēkṣā) of phenomena.

- Argues that proving reality solely through absolute relativity leads to the non-establishment of any entity, as each entity would depend on another, creating an infinite regress or a lack of independent existence.

- Proving reality through absolute non-relativity fails to explain the interrelationships between things, like the connection between a cause and its effect, or attributes and their substratum.

- Establishes that relationships and attributes are understood through a combination of relative and non-relative perspectives.

-

Chapter 6: Sarvathā Hētu-Siddha tathā Āgama-Siddha Ekāntōṁ Sadōṣatā (Fallacies of Absolute Proofs by Reason or Scripture):

- Critiques the exclusive reliance on reason (hetu) or scripture/authority (āgama) for establishing truth.

- Argues that relying solely on reason makes perception and scriptural authority irrelevant.

- Conversely, relying solely on scripture makes reasoning and critical inquiry obsolete.

- The conflict between different scriptural traditions further undermines the claim of absolute scriptural authority.

- Proposes that both reason and scripture, when correctly understood in conjunction with syādvāda, contribute to valid knowledge.

-

Chapter 7: Antaraṅgārthatā-Ekāntaṁ Sadōṣatā (Fallacy of Internalism/Subjectivism):

- Critiques the doctrine that only internal consciousness (vijñapti-mātra) is real, and external objects are mere mental constructs.

- Argues that if only consciousness is real, then all knowledge and speech become false or mere illusions (pramāṇābhāsa).

- This leads to a contradiction, as the very assertion of internalism needs to be grounded in some form of valid knowledge.

- The reliance on consciousness alone cannot explain the shared experience of reality or the distinction between valid and invalid knowledge.

- The author emphasizes that both internal consciousness and external objects are real and perceived through valid means of knowledge.

-

Chapter 8: Daiva-Pauruṣa Ekāntōṁ Sadōṣatā (Fallacy of Absolute Fate or Absolute Effort):

- Examines the debate between determinism (daiva-vāda, fate) and free will (pauruṣa-vāda, effort).

- Argues that attributing all outcomes solely to fate makes human effort meaningless.

- Conversely, attributing all outcomes solely to effort negates the role of destiny or external circumstances.

- The Jain perspective reconciles these by stating that actions are influenced by both inherent predispositions (related to karma/destiny) and one's own effort.

-

Chapter 9: Pāpa-Puṇya (Merit and Demerit):

- Discusses the nature of merit (puṇya) and demerit (pāpa) and their relation to actions.

- Critiques the idea that merit/demerit is solely based on causing happiness or unhappiness to others, or to oneself.

- The commentator emphasizes that the Jain understanding links merit and demerit to the presence or absence of viśuddhi (purity of consciousness, often associated with positive mental states) and saṁkleśa (affliction of consciousness, associated with negative mental states), which are influenced by one's intentions and actions, rather than simply the outcome.

-

Chapter 10: Bandha-Mokṣa (Bondage and Liberation):

- Critiques simplistic views on bondage and liberation.

- For example, the view that ignorance (ajñāna) causes bondage and knowledge (jñāna) causes liberation is challenged, as ignorance can persist even with partial knowledge, and true liberation requires complete eradication of passions (moha).

- The Jain perspective emphasizes that bondage is primarily due to passions (moha) associated with ignorance, while liberation is achieved through the absence of these passions, even with partial knowledge, provided it is free from moha.

- Reiterates the importance of syādvāda in understanding complex concepts like bondage and liberation, which are not absolute but rather conditional.

Contribution of Acārya Samantabhadra:

Acārya Samantabhadra is credited with revitalizing Jain philosophy by systematically articulating and defending anekānta and syādvāda. He established the logical framework for understanding reality through multiple viewpoints, providing rigorous arguments against various absolutist schools of thought. His work laid the foundation for subsequent Jain philosophical developments.

Significance of the Text:

Āptamīmāṁsā is considered a foundational text in Jain epistemology and metaphysics. It demonstrates the intellectual rigor and philosophical depth of Jainism, offering a sophisticated approach to understanding complex existential questions and refuting opposing philosophical systems. The text is essential for anyone seeking a deep understanding of Jain philosophical tenets and its logical argumentation.