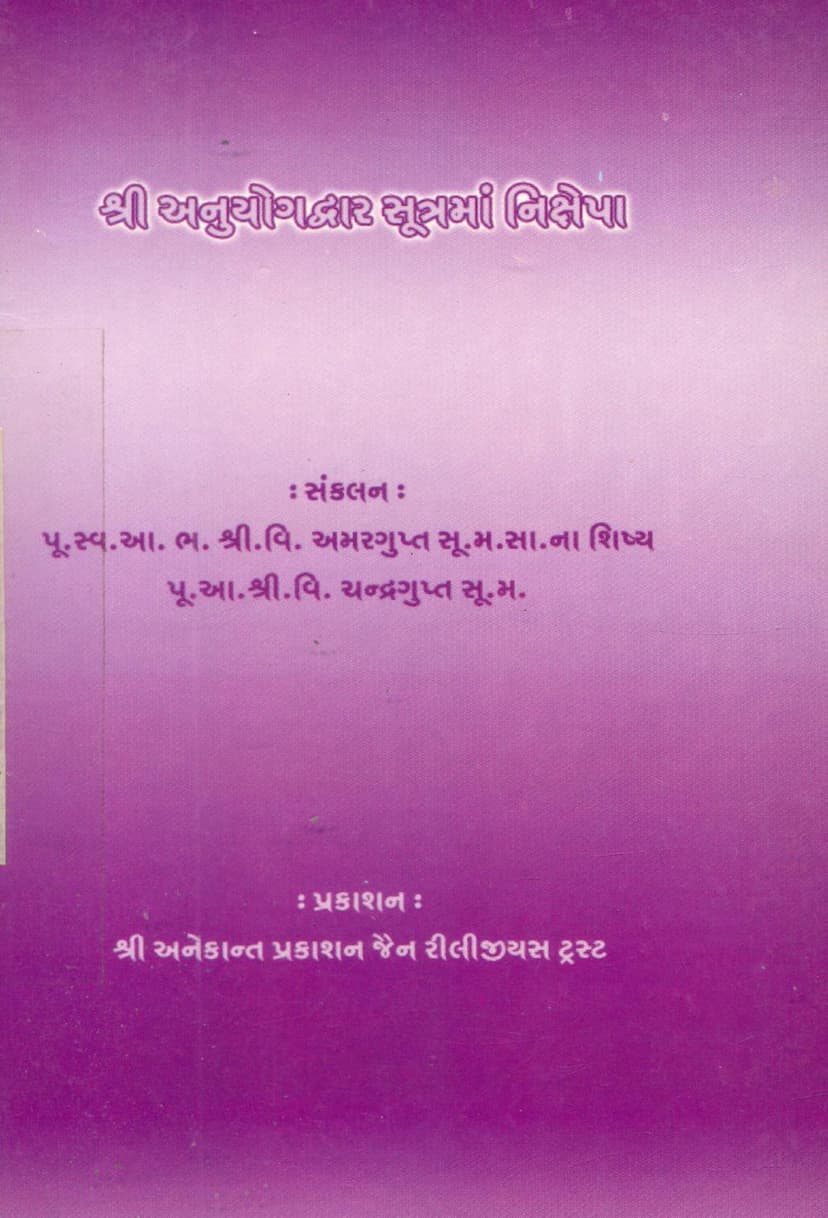

Anuyogdwar Sutra Ma Nikshepa

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This document is a Gujarati-language summary and explanation of the Nikshesps (categories of exposition) as described in the Jain text Anuyogdwar Sutra. The book is compiled by P.A. Shri. Vi. Chandragupta Sum. M., a disciple of P.S.A. Bh. Shri. Vi. Amargupta Sum. M., and published by Shri Anekant Prakashan Jain Religious Trust.

The core purpose of the book is to clarify the concept of Nikshesps to help readers understand Jain philosophy more accurately, especially when the path of understanding seems obscured. It emphasizes the importance of grasping the four universal Nikshesps: Nama (Name), Sthapana (Establishment/Representation), Dravya (Substance/Matter), and Bhava (State/Quality/Essence).

Here's a breakdown of each Nikshep as explained in the text:

1. Nama (Name):

- This refers to the name given to an object or concept.

- It can be a word that perfectly corresponds to its meaning.

- It can also be a name used for something else, even if it doesn't accurately reflect its inherent meaning (e.g., naming a cow "Indra").

- It also includes names that are arbitrary, without any etymological basis.

- The text distinguishes between names that accurately represent their meaning and those that are used conventionally or even incorrectly.

2. Sthapana (Establishment/Representation):

- This involves creating a representation of something, either for a short or long duration.

- This representation can be in various forms like wood, stone, books, paintings, or even abstract shapes and symbols.

- It can be a likeness of the actual object or something dissimilar, but established with the intention of representing it.

- The text emphasizes that Sthapana is about the intention and representation, regardless of whether the represented object is alive or dead.

- It clarifies that Sthapana is distinct from Dravya (substance). The state of being alive or dead does not change the Sthapana.

3. Dravya (Substance/Matter):

- This refers to the cause of a thing, either in the past or the future.

- It can be a living being (sentient) or an inanimate object (non-sentient).

- Dravya is often understood as the underlying substance or the potential for something to exist or to have existed.

- The text uses examples like the clay from which a pot is made, or a person who was an "Indra" in a past life and is now a human, being considered a "Dravya-Indra" as they were the cause of the past existence.

- It further categorizes Dravya into two main types based on Agam (scriptural knowledge) and No-Agam (non-scriptural understanding).

- Agam-based Dravya: Refers to someone who knows the meaning of a term (like "Indra") but does not actively use or practice it in their current life, or their knowledge is dormant.

- No-Agam-based Dravya: This is further divided into three types:

- Jnya Sharir (Knowledge Body): The physical body of someone who possessed the knowledge but is now deceased.

- Bhavya Sharir (Potential Body): The physical body of someone who will acquire the knowledge in the future.

- Dravya in relation to the Body: This category includes various aspects, such as the body of those who performed a ritual without proper scriptural understanding, or even mundane daily activities like washing one's face, which can be considered Dravya in a broader sense, especially when viewed as a cause of something (even if secondary or non-essential).

4. Bhava (State/Quality/Essence):

- This refers to the intrinsic nature or the actual state of being of a thing.

- It is about the essence and experience of the subject.

- The text states that Bhava is associated with the experience of a state or action.

- An example is an "Indra" experiencing the glory and powers of being an Indra, which is his Bhava.

- It also categorizes Bhava based on Agam and No-Agam:

- Agam-based Bhava: Refers to those who possess scriptural knowledge and actively practice it, experiencing its effects.

- No-Agam-based Bhava: This is also divided into three types:

- Laukik (Worldly): Performing rituals or reading scriptures for worldly gains or entertainment, with actual usage and experience.

- Kutprāvachanik (Badly Conducted): Practices by ascetics of other faiths that are performed with some level of experience but are considered contrary to Jain teachings.

- Lokottar (Transcendental): The practice of essential Jain rituals (like the six Avashyaks) with full concentration and understanding by ascetics and devout laypeople.

The book emphasizes that understanding these Nikshesps is crucial for accurately comprehending Jain scriptures and avoiding misinterpretations. It highlights the subtle differences between them, particularly between Dravya and Sthapana, and stresses the importance of the speaker's intention when interpreting the meaning. The ultimate goal is to use this understanding to progress on the spiritual path towards liberation.