Agamanusar Muhpatti Ka Nirnay

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, focusing on the key arguments and structure:

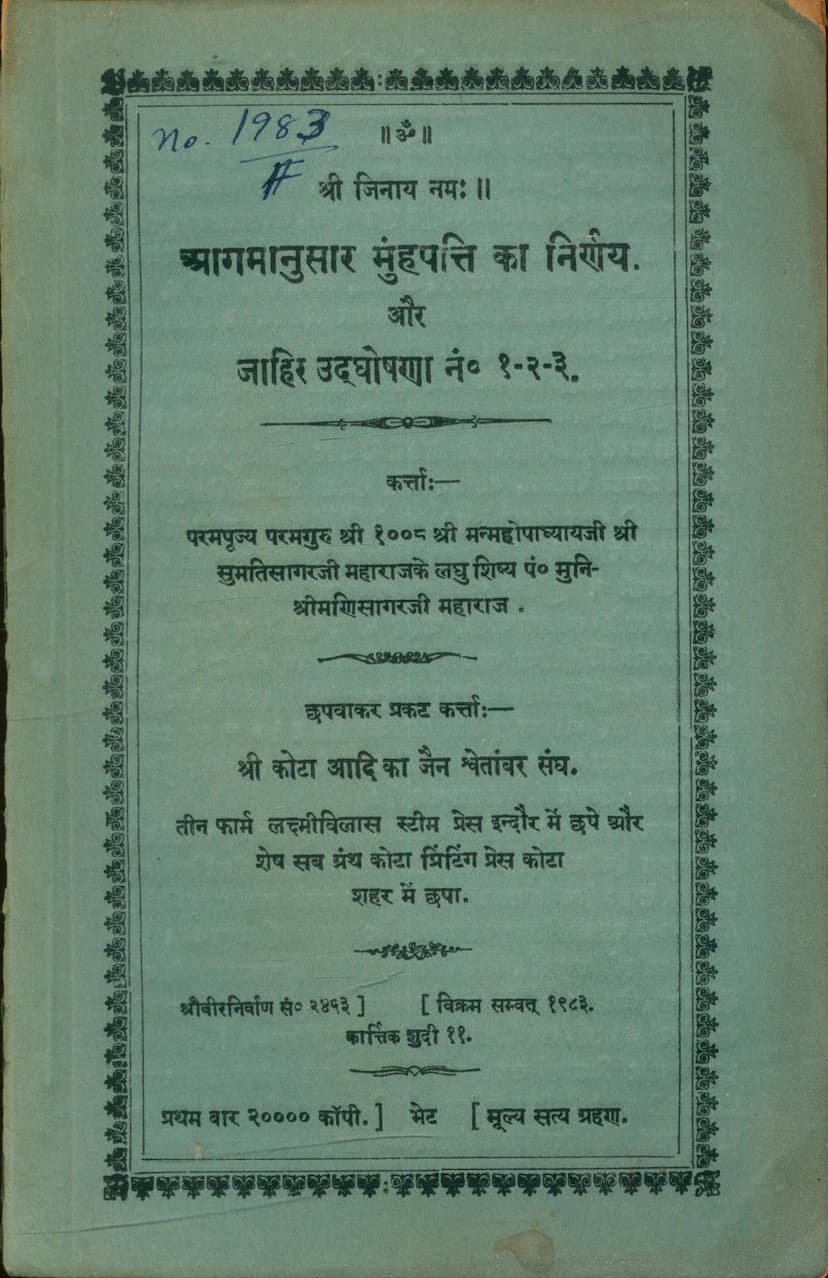

Book Title: Agamanusar Muhpatti Ka Nirnay (The Decision Regarding Mouth-Cover According to the Agamas) Author: Pandit Muni Shrimanisaagarji Maharaj (disciple of Paramguru Shri Sumatisagarji Maharaj) Publisher: Shri Kota Aadi ka Jain Shwetambar Sangh Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/032020/1

Overall Purpose: This extensive text, presented primarily as a series of "Jahir Udghoshna" (Public Declarations/Announcements), is a polemical work by Muni Shrimanisaagarji Maharaj. Its primary objective is to refute the practice of wearing a mouth-cover (muhpatti) at all times as advocated by a sect referred to as "Dhundhiya" (also known as Sthanakvasi, Baish Tole, or Sadhu Margi). The author strongly argues that this practice is contrary to the Jain Agamas (scriptures) and the teachings of the Tirthankaras.

Key Arguments and Structure:

The text is structured in a way that first addresses the reader directly, explains the author's motivation, and then proceeds with detailed arguments and refutations.

Page 1-2: Introduction and Author's Motivation

- Acknowledgement: The book is presented as a decision regarding the muhpatti according to the Agamas, authored by Muni Shrimanisaagarji Maharaj, and published by the Kota Jain Shwetambar Sangh.

- Context and Motivation: The author states that many do not want controversial books, but due to the extensive propagation of books by "Sthanakvasis" (arguing for continuous muhpatti), falsely citing Agamas and ancient texts, and unfairly accusing those who do not wear it continuously, he felt compelled to write. The author's intent is to present the correct decision with strong reasoning and scriptural evidence to clarify the truth for honest souls.

- Terminology: The author notes that "Dhundhiya" is a common and accepted name for the sect, using a humorous couplet to explain this. He requests that no one be offended by this term.

- Apology for Errors: The author apologizes for delays in publication and any printing errors due to press difficulties, attributing them to press, vision, and authorship factors. He urges readers to read the initial announcements before the main text and accept only the truth.

- Call to Action: The author encourages readers to read the book, teach others, share it, and spread it within the Shwetambar Jain community to facilitate the examination of truth versus falsehood. He emphasizes abandoning falsehood like a snake shedding its skin and embracing truth like a wish-fulfilling gem.

Page 3-17: Jahir Udghoshna No. 1 (Public Declaration No. 1)

This section lays down the fundamental principles of Jainism and the path to liberation.

- The Difficulty of Liberation: It begins by stating that while worldly pleasures and kingdoms are accessible, attaining Samyak Darshan (right faith) in the teachings of the Tirthankaras, which is essential for liberation, is extremely difficult.

- The Path to Moksha: Liberation (Moksha) is achieved through Samyak Darshan (right faith), Samyak Gyan (right knowledge), and Samyak Charitra (right conduct). Without these three, liberation is impossible.

- Adherence to Jinavachana (Tirthankara's Words): The core message is that strict adherence to the Tirthankaras' words is paramount. Deviation from their teachings, even with rigorous ascetic practices (tapas, japa, dhyana), virtuous actions (daya, dan, shila), or adherence to vows, is futile for liberation and leads to further entanglement in the cycle of birth and death.

- Consequences of Deviation (Utsutra Prarupana): The text highlights the severe consequences of deviating from the Agamas or spreading false doctrines (utsutra prarupana). It cites the example of Jamali, who, despite severe practices, fell from liberation due to one transgression. Those who deviate become misguided, fall into lower births (as gods or animals), and struggle to attain the seed of liberation (Samyak Darshan) again.

- The Danger of False Preaching: Spreading false doctrines is equated to the destruction of bodhi (liberation) and leads to an endless cycle of rebirth. Virtuous individuals remain steadfast against false teachings, even at the cost of their lives.

- The Role of a Guru: A guide who leads astray is considered more culpable than someone who commits violence. Those who follow false guides also fall from right faith and increase their worldly suffering.

- The Duty of a True Jain: A true Jain should abandon falsehood and embrace truth, actively engaging in righteous conduct.

- Characteristics of a Samyaktvi (True Believer): A Samyaktvi is characterized by honesty, avoids deception and stubbornness, rectifies mistakes when understood, and prioritizes Jinagya (Tirthankara's commands) over worldly considerations like shame or lineage. They desire self-welfare and liberation. Even minor acts performed with right faith and adherence to Jinagya yield immense benefits.

- Characteristics of a Mithyatvi (False Believer): A Mithyatvi, even if outwardly appearing virtuous or adopting the guise of a monk, clings to falsehoods, prioritizes worldly recognition, and stubbornly upholds wrong beliefs, leading to karmic bondage and suffering.

Page 8-27: Jahir Udghoshna No. 2 (Public Declaration No. 2)

This section directly addresses the Dhundhiya practice of wearing the muhpatti continuously and refutes their scriptural claims.

- The Origin of Continuous Muhpatti: The author traces the origin of this practice to a sect member named Lavji in Vikram Samvat 1709, who introduced it based on his own interpretation, claiming it was for greater compassion (daya) and avoiding harm to subtle beings. The author argues this was a new practice (nayee riti) that went against established tradition.

- Refutation of Dhundhiya Claims: The author systematically debunks the Dhundhiya arguments by:

- Challenging historical claims: He states that in regions with large Jain populations (Gujarat, Kathiawar, etc.), no monks ever wore the muhpatti continuously. The Dhundhiya claim that such monks went to "Arya-desh" (non-Jain lands) is labeled as a blatant lie.

- Analyzing specific scriptural references: The author meticulously analyzes various verses cited by the Dhundhiyas from scriptures like Bhagavati Sutra, Shaataka Sutra, Vipaka Sutra, and Mahanishith Sutra. He demonstrates how the Dhundhiyas distort the meaning, take verses out of context, or misinterpret them to support their practice.

- Bhagavati Sutra (Shakrendra): The verse about speaking with a hand or cloth in front for pure speech is interpreted as a specific instruction for that moment of speaking, not a mandate for continuous wearing.

- Shaataka Sutra & Shaataji Sutra (Jamali/Meghkumar): The mention of householder barbers tying cloths to protect princes from bad odors during hair-cutting is misinterpreted as monks wearing muhpatti.

- Vipaka Sutra (Gautam Swami & Mrigaputra): The account of Mrigaputra's father requesting Gautam Swami to tie a cloth to protect from the odor is interpreted to show Gautam Swami had the muhpatti in hand, not already tied, and the request was for protection from a specific stench, not a general rule.

- Mahanishith Sutra: The author refutes claims that Mahanishith mandates continuous muhpatti, explaining that the text refers to keeping the muhpatti ready to use when speaking, not permanently tied.

- The Fallacy of "Hand-patti" vs. "Mukh-patti": The author rejects the Dhundhiya distinction between "mukh-patti" (mouth-cover) and "haath-patti" (hand-cover), arguing that the cloth is called muhpatti regardless of whether it's held or worn.

- Uselessness of Continuous Wearing: The author points out the futility of wearing the muhpatti during periods of silence (maun, kausagga) or meditation.

- The Problem of Spittle and Life: He argues that continuously wearing a muhpatti leads to it becoming soiled with spittle, breeding countless five-sensed (panchendriya) beings, causing immense violence.

- Misinterpretation of Scriptural Terms: The Dhundhiya interpretation of "muhanantagema" as a "rope" (dora) for tying the muhpatti is debunked as a childish and ignorant misunderstanding.

- Fabrication in Texts: The author alleges that the Dhundhiya sect has altered texts, citing examples in the "Samavara Vrat Vyakhyan" and "Haribal Machhli Ras," where verses were allegedly changed or misrepresented to support their views.

- Inconsistent Practices: He criticizes the Dhundhiyas for their inconsistent practices, such as adjusting the muhpatti casually, which contradicts the idea of strict adherence.

- The Dhundhiya Doctrine's Flaws: The author enumerates 36 faults of continuously wearing the muhpatti, including false accusations against other sects, misrepresenting scriptures, causing loss of bodhi, and engaging in practices that lead to further karmic bondage.

- Critique of Dhundhiya Lifestyle: The latter part of Udghoshna No. 2 delves into a critique of the Dhundhiya sect's general practices, highlighting numerous instances of violence and deviation from Jain principles:

- Extensive Violence in Daily Practices: This includes violence in their rituals, festivals, lifestyle, use of materials, and interactions with the world, such as:

- Long ochhas (sweeping cloths) leading to harm to air-bodied beings (vayukaya).

- Tying blankets in a way that harms air-bodied beings.

- Inconsistent muhpatti wearing, causing harm.

- Violence associated with building structures (sthanak), erecting banners, and organizing festivals.

- The use of printed materials and the violence involved in their production and distribution.

- The tradition of inviting large numbers of people to festivals, leading to significant violence from travel, food preparation, and lodging.

- The use of impure water and contaminated food items (like jaggery mixed with milk, leftover food, certain types of sweets, and even alleged consumption of items like jalebis and pickles).

- The practice of using urine for purification in certain situations, which is deemed unscriptural and impure.

- The controversial claim about the harmlessness of nose breathing versus mouth breathing, which the author refutes.

- The use of urine instead of water for purification, the impurity of urine itself, and the lack of scriptural basis for this.

- The practice of certain Dhundhiya monks and nuns living in houses (vasthishala) and having personal attendants, contradicting the principle of non-possession.

- The adoption of specific names and customs that deviate from ancient Jain traditions.

- The lack of adherence to proper purification rituals for water and food, leading to violence.

- The concept of "vasivastra" (used clothing) and its implications.

- The acceptance of food from houses with specific ritualistic impurities.

- The interpretation of scripture regarding the acceptable time for using water, leading to the acceptance of impure water.

- The use of impure cooking ingredients and methods.

- The practice of leaving corpses uncremated for extended periods, leading to violence and social stigma.

- The worship of photos and relics of their deceased gurus, seen as a deviation from worshipping Tirthankaras.

- The lack of adherence to regulations regarding menstruation and impurity.

- The interpretation of scriptural passages related to purity and impurity.

- Hypocrisy and Deception: The author accuses the Dhundhiyas of hypocrisy, claiming they preach compassion while engaging in significant violence, and of using scripture to mislead the public.

- Financial Misappropriation and Self-Aggrandizement: The text hints at financial irregularities and self-serving practices within the sect.

- Extensive Violence in Daily Practices: This includes violence in their rituals, festivals, lifestyle, use of materials, and interactions with the world, such as:

Page 27-53: Jahir Udghoshna No. 3 (Public Declaration No. 3)

This section focuses on the issue of night-time water retention and the decision regarding the "danda" (staff), further refuting Dhundhiya practices and claims.

- Decision on Night-time Water: The author argues that while collecting food and water for consumption is forbidden at night, retaining water for purification purposes after attending to bodily needs (bowel movements, urination) is permissible and even necessary according to scriptural interpretation. He criticizes the Dhundhiyas for not retaining water for purification and for their reliance on impure methods.

- The Danda (Staff): The author presents extensive scriptural evidence from various Agamas (Bhagavati, Nishith, Acharanga, Dashavaikalika, etc.) demonstrating that the danda is a legitimate and beneficial accessory for Jain monks. He lists 15 advantages of carrying a danda, including safety, assistance in travel, support during illness, carrying alms, and serving as a reminder of spiritual principles.

- Critique of Dhundhiya Denial of Danda: The author refutes the Dhundhiya claim that the danda is unnecessary or scripturally unsupported, showing how they have distorted or omitted relevant scriptural passages. He criticizes their hypocrisy in accepting other valid accessories while denying the danda.

- The Importance of Purity and Respect: The author emphasizes the importance of purity in all actions and adherence to scriptural guidelines regarding impurity and its purification. He criticizes the Dhundhiya disregard for these principles, leading to social criticism and karmic consequences.

- The True Nature of "Dhundhiya": The author reiterates that the term "Dhundhiya" signifies their continuous search for true dharma, which they have yet to find. Their various names (Sthanakvasi, Sadhu Margi, etc.) are seen as attempts to mask their deviation.

- The Problem of "Luka Gachha" and Lavji: The text extensively discusses the controversial figure of Lavji and the establishment of the "Luka Gachha" by Lavji, who allegedly introduced practices contrary to established Jain traditions and scriptures, including the continuous wearing of the muhpatti. The author views this as a distortion of the original Jain teachings and a departure from the path of liberation.

Page 79-89: Final Sections

- Rejection of Dhundhiya Names: The author rejects the names used by the Dhundhiya sect (Dhundhiya, Baish Tole, Sthanakvasi, Sadhu Margi, Luka Gachha) as being contrary to Jain tradition and the teachings of the Tirthankaras.

- Critique of "Sthanakvasi": The author criticizes the term "Sthanakvasi" (one who resides in a sthanak or a building) as being contrary to the spirit of Jain monasticism, which emphasizes renunciation and detachment from material possessions, contrasting it with the ideal of an "Angaar" (one who is homeless and detached).

- Critique of "Sadhu Margi": The author argues that "Sadhu Margi" is an inappropriate self-appellation, as the true path is the "Jain Marg" or "Arhat Marg" established by the Tirthankaras. Using "Sadhu Margi" is seen as an attempt to elevate their own sect above the original teachings.

- The "Dandi" Controversy: The author defends the practice of carrying a danda, countering the Dhundhiya's derogatory use of the term "Dandi" to mock those who carry it. He argues that the danda is a scripturally sanctioned and beneficial tool.

- Critique of Dhundhiya Interpretations of Scripture: The author highlights the Dhundhiya's misinterpretations and selective use of scripture to support their practices, accusing them of fraud and deceit.

- Call for Renunciation of Falsehood: The text concludes with a strong appeal to the Dhundhiya community to abandon their incorrect practices and embrace the true path of Jainism as taught by the Tirthankaras.

In essence, the book is a comprehensive and passionate defense of traditional Jain practices and scriptural authority, aiming to expose and refute what the author perceives as the erroneous and harmful innovations introduced by the Dhundhiya sect regarding the muhpatti and other aspects of monastic conduct.