Agam 31 Chulika 01 Nandi Sutra Sthanakvasi Gujarati

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, which appears to be a Gujarati translation and commentary of the Nandi Sutra, authored by Ghasilal Maharaj and published by the A B Shwetambar Sthanakwasi Jain Shastroddhar Samiti. The text outlines various aspects of Jain philosophy, particularly focusing on knowledge (jnana) and the rules and principles associated with its study.

Here's a breakdown of the key themes and information presented:

1. Introduction and Mangalacharan (Invocation):

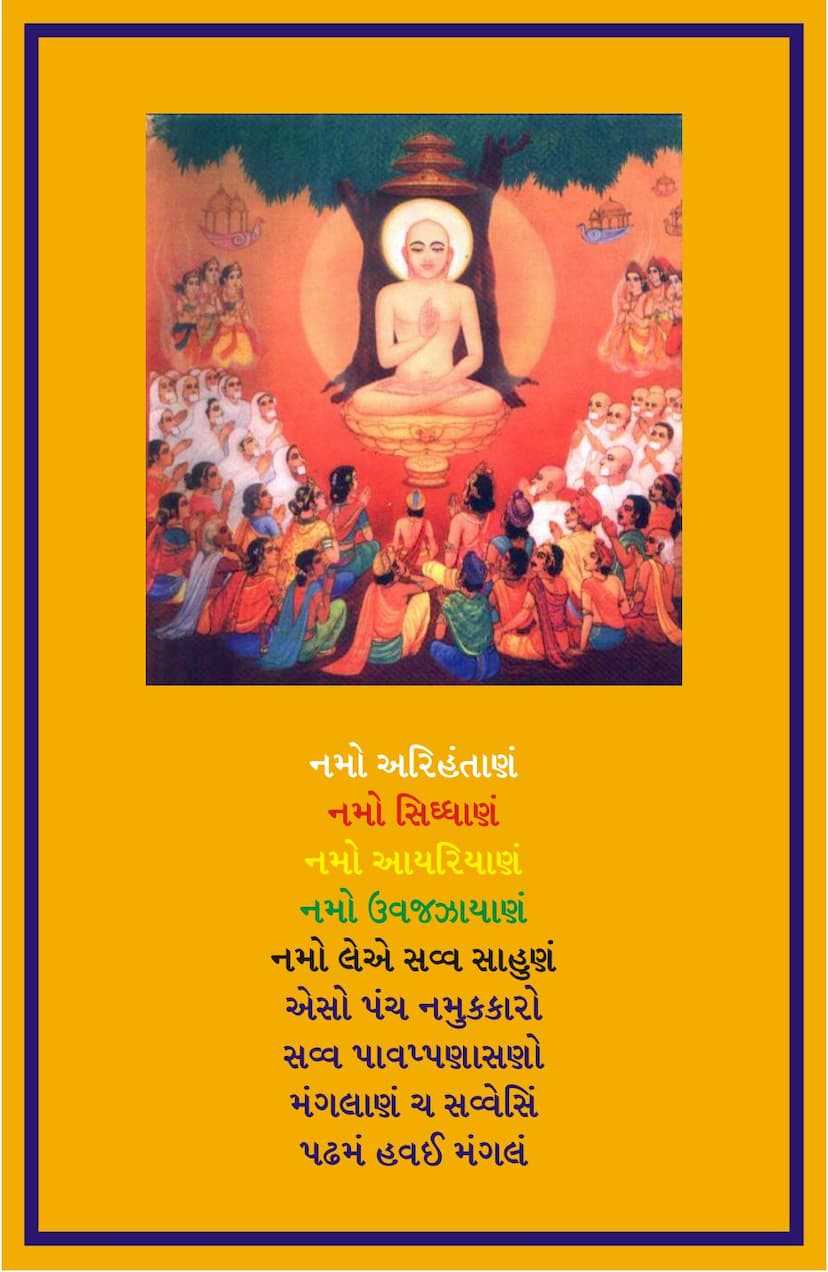

- The text begins with the traditional Jain invocation: "Namo Arihantanam, Namo Siddhanam, Namo Acharyanam, Namo Upadhyayanam, Namo Loye Savva Sadhunam." This Panch Namaskar Mantra is described as the destroyer of all sins and the foremost auspicious chant.

- It acknowledges the lineage of spiritual teachers and the contribution of Acharya Shri Ghasilalji Maharaj.

- The publication is part of a larger "Jain Agam Prakashan Yojana."

2. The Nandi Sutra:

- The title "Shri Nandi Sutra" is clearly presented.

- It is noted to be enriched with the commentary "Gyanchandrika" by Jainacharya Shri Ghasilalji Maharaj.

- The text includes Hindi and Gujarati translations.

- The publication was a collaborative effort, with Munishri Shri Kanhaiyalalji Maharaj as the supervisor and Shri Shantilal Mangaldasbhai Mahoday from Rajkot as the publisher, supported by financial assistance from Shri Bhogilal Chhaganlalbhai Bhavsar.

- The first edition was published in Vikram Samvat 2014 (Veer Samvat 2484, AD 1958) with 1000 copies.

3. Rules for Swadhyaya (Study): A significant portion of the provided text is dedicated to the rules and etiquette for studying the Nandi Sutra (and Jain Agamas in general). These include:

- Timing: The original text (Mool Path) should be studied during the first and fourth quarters of the day and night.

- Prohibited Times: Study is not recommended during specific periods like Ushakal (dawn), Sandhyakal (dusk), midday, and midnight. A general rule is given for the 24 minutes before and 24 minutes after sunrise as a period not to be studied.

- Gender Restrictions: Women during menstruation are not permitted to study or be in the presence of the sutra during study. Reading should occur in a separate, unaffected room.

- 32 Astadhyaya Prasang (Occasions of Non-Study): These are detailed and categorized into two main groups:

- 10 Astadhyaya related to the Sky (Akash Sambandhi):

- Ulkapata (Meteor Shower): 1 Pahar (3 hours) of non-study.

- Digdaha (Directional Fire/Excessive Redness): No study.

- Garjarav (Thunderous Clouds): 2 Pahar (6 hours) of non-study.

- Nighata (Divine Roar/Thunderbolts): 8 Pahar (24 hours) of non-study.

- Vidyut (Lightning): 1 Pahar (3 hours) of non-study.

- Yupak (Specific twilight conditions): 1 Pahar of the first quarter of the night.

- Yakshadipata (Light resembling lightning): No study.

- Dhumika Krishn (Autumnal fog): No study.

- Mahika Shvet (Winter fog): No study.

- Rajoudghat (Dust storm covering the sun): No study.

- 10 Astadhyaya related to the Physical Body (Audarik Sharir Sambandhi):

- Bones, flesh, and blood exposed and not fully burnt by fire, or unwashed by water, or visible: No study.

- Broken egg: Non-study.

- Excreta/Urine: Until visible or its smell is present: Non-study.

- Cremation Ground (Smashan): 100 hands distance around the area: Non-study.

- Lunar Eclipse (Chandragrahan): 8 to 12 Muhurta (time units) of non-study.

- Solar Eclipse (Suryagrahan): 12 to 16 Muhurta of non-study.

- Rajavyagrata (Royal disturbances/war): During and for 1 day/night after: No study.

- Patan (Death of a king/leader): Until cremation and appointment of successor: No loud study.

- Audarik Sharir (Dead body of a five-sensed being): Inside or within 100 hands of the Upashraya (monastery): No study until the body is removed.

- Four Mahotsavas and Four Pratipada (Festivals and their following days): 8 days covering Ashadh Purnima, Ashwin Purnima, Kartik Purnima, Chaitri Purnima, and their following 4 Pratipada days.

- Reddishness in directions at dawn/dusk: 1 Ghadi (48 mins) before and after sunrise/sunset: No study.

- Midday and Midnight: 1 Ghadi before and after: No study.

- 10 Astadhyaya related to the Sky (Akash Sambandhi):

- Clarification: The text clarifies that these non-study rules are for the original text (Mool Path) and not for translations in Gujarati or other languages. It emphasizes the importance of Vinaya (respectful conduct) and following the guidance of elders.

4. Table of Contents (Anukramanika):

- The text includes a detailed table of its contents, listing various topics covered in the Nandi Sutra, such as:

- Definition of various types of knowledge (Mati, Shrut, Avadhi, Manahparyaya, Kevaljnana).

- The nature and characteristics of each type of knowledge.

- Analysis of terms like "Pratyaksh" (direct perception) and "Paroksh" (indirect perception).

- Detailed explanations of Avadhijnana and Manahparyayajnana, including their types, scope, and conditions.

- Discussions on Karma Prakriti (types of karmas), including Sarvghati (completely affecting) and Deshghati (partially affecting) karmas.

- The concept of Bhav (states of existence) and their relation to karma.

- The significance of various examples (Drishtanta) used to illustrate concepts.

5. Explanations of Key Concepts: The text then delves into detailed explanations of various types of knowledge, their etymology, and characteristics:

- Matijnana (Sense-based knowledge): Derived from the root "Mani" and the suffix "dhi," signifying apprehension. It is explained as the knowledge gained through the five senses and the mind.

- Shrutajnana (Scriptural knowledge): Derived from "Shruta" (heard), this knowledge comes from listening to scriptures. It is also linked to the listener (shrota).

- Avadhijnana (Clear knowledge of subtle or distant objects): Explained through etymology relating to "Avadhi" (limit) and "dhi" (knowledge), signifying knowledge within a specific limit. It is the direct perception of subtle or distant matter.

- Manahparyayajnana (Knowledge of others' thoughts): Derived from "Manah" (mind) and "Paryaya" (thought), this refers to the knowledge of others' mental states.

- Kevalajnana (Omniscient knowledge): Explained as absolute, unimpeded, complete, and unique knowledge.

6. Detailed Discourse on Types of Knowledge: The bulk of the content provides detailed explanations of each of the five types of knowledge (Panchvidh Jnana):

- Matijnana: Explained in terms of its derivation, its connection to the senses and mind, and its various classifications.

- Shrutajnana: Explained as knowledge gained through hearing, its relationship with memory and apprehension, and its dependence on language.

- Avadhijnana: Described in detail, including its types (Bhavapratyayika, Kshayopashamika), scope, and the conditions for its attainment. The text clarifies the subtle differences between knowing and seeing and discusses the temporal and spatial extent of Avadhijnana.

- Manahparyayajnana: Explained as the knowledge of others' thoughts, its limitations, and its exclusive occurrence in humans. The text discusses the conditions for its attainment, such as specific character traits and the absence of attachment.

- Kevalajnana: Presented as the ultimate and perfect knowledge, free from all limitations and karmic obstructions. Its various meanings (complete, pure, unique, infinite) are explored.

7. Karma and Jnana: The text emphasizes that knowledge arises from the subsidence (Kshaya or Kshayoapshama) of specific karmas, particularly Jnanavarniya (knowledge-obscuring) karmas. The interplay of karma and the attainment of various levels of knowledge is a recurring theme.

8. Examples (Drishtanta): The text uses numerous illustrative examples (Drishtanta) to explain complex philosophical concepts. These range from the metaphorical to the practical, often involving princes, ministers, merchants, and common people, demonstrating the application of knowledge, logic, and understanding in various situations. The descriptions of these examples are quite detailed.

9. Debates and Philosophical Arguments: The text addresses potential doubts and refutes opposing philosophical viewpoints (e.g., Mimansakas, Vaisheshikas) that may contradict Jain principles, especially concerning the nature of the soul, knowledge, and liberation.

10. Classification of Karmas: The text categorizes karmas into Sarvghati (completely affecting) and Deshghati (partially affecting) based on their "rasa" (flavor or intensity). It lists the specific karmas that fall into each category.

11. Vinaya and Etiquette: The emphasis on Vinaya (respectful conduct) towards teachers and scriptures is evident throughout the text, particularly in the rules for Swadhyaya.

In essence, this document is a pedagogical text designed to explain the Nandi Sutra, a foundational Jain scripture, by breaking down complex philosophical concepts, defining terms, and providing practical rules for spiritual practice and study, all within the framework of Jain cosmology and epistemology.