Agam 29 Mool 02 Dasvaikalik Sutra Part 01 Sthanakvasi

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary of the provided Jain text, "Agam 29 Mool 02 Dasvaikalik Sutra Part 01 Sthanakvasi" by Ghasilal Maharaj, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Agam 29 Mool 02 Dasvaikalik Sutra Part 01 Sthanakvasi Author: Ghasilal Maharaj Publisher: A B Shwetambar Sthanakvasi Jain Shastroddhar Samiti Catalog Link: https://jainqq.org/explore/006367/1

Overall Context:

This text is the first part of the Dasvaikalik Sutra, a significant Jain scripture revered by the Shwetambar Sthanakvasi tradition. The volume is presented with a commentary ("Acharmani Manjusha") by Ghasilal Maharaj, highlighting its importance for both scholarly monks and the general public. The work emphasizes the Jain path to liberation through the dual principles of knowledge (Gyan) and action (Kriya), underscoring that without the integration of both, the spiritual journey remains incomplete.

Key Themes and Content:

The provided pages mainly focus on:

-

Invocation and Acknowledgements:

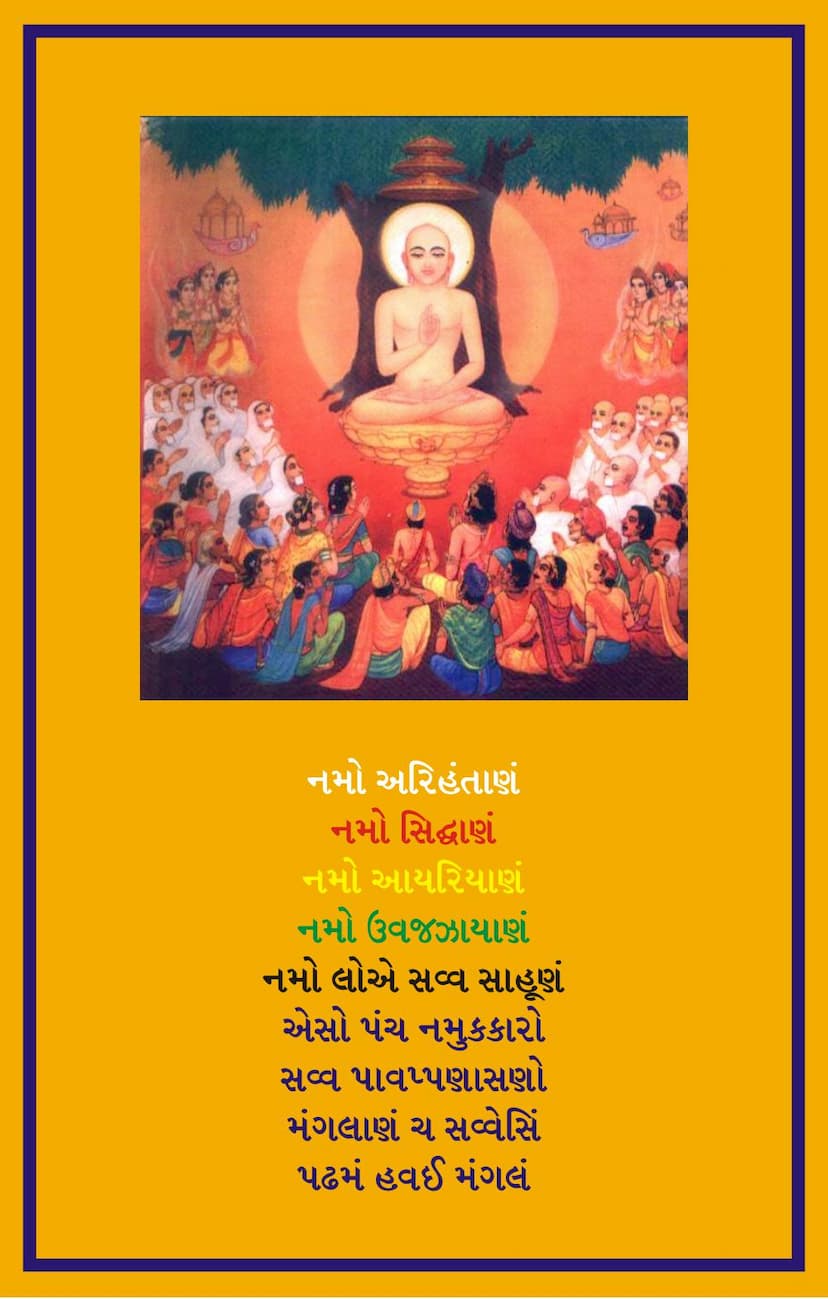

- Page 1-2: Begins with the traditional Jain invocation (Namo Arihantanam, Namo Siddhanam, etc.), known as the Panch Namaskara Mantra, which is considered the essence of Jainism and the destroyer of sins. It also mentions the "Agam Prakashan Yojana" and acknowledges Acharya Ghasilalji Maharaj and the organizer Shri Chandra P. Doshi.

- Page 3-5: Introduces the book title, Dasvaikalik Sutra Part 01, and provides publication details, including the third edition, publisher, and pricing. It also includes a Sanskrit verse expressing the author's hope for his work to be recognized by those of similar understanding and a confident outlook for future appreciation. The publication details also indicate the year 1974 (Vir Samvat 2500, Vikram Samvat 2031).

- Page 6-27: This significant portion comprises numerous "Sammatipatra" (Letters of Endorsement/Appreciation) from various prominent Jain scholars, monks, Mahasatijis, professors, and respected householders. These testimonials, primarily from the era of Acharya Shri Atmaramji Maharaj, praise the comprehensive and simple commentary by Ghasilal Maharaj. They highlight the clarity, accuracy, and profound explanation of Jain principles, especially concerning the conduct (Achar) of monks and the philosophy of Ahimsa. Many testimonials specifically commend the author's ability to present complex scriptural ideas in an accessible manner for all sections of society.

-

Introduction to the Dasvaikalik Sutra:

- Page 7-9: The "Prastavana" (Preface) eloquently explains the Jain concept of dharma as twofold: Shrutacharita (knowledge-based conduct) and Charitra (actual practice). It emphasizes that liberation (Moksha) is achieved through both knowledge and action, stressing the inseparability of the two. The preface critiques both extreme "Nishchaya-vadis" (those who only focus on ultimate truth) and "Vyavahar-vadis" (those who only focus on conventional truth), highlighting the importance of understanding both according to "Syadvada" (the doctrine of manifold viewpoints). It uses the analogy of eyes to illustrate the necessity of both Nayas (standpoints) for understanding dharma. The preface also draws a parallel between the necessity of action for liberation and a drowning person needing to move their limbs to swim, concluding that knowledge alone is insufficient without action. The Dasvaikalik Sutra is presented as a text that elucidates the principles of conduct for monks, incorporating knowledge.

-

Summary of the Ten Chapters of Dasvaikalik Sutra (Page 8-9): The text provides a brief overview of each of the ten chapters of the Dasvaikalik Sutra, indicating the scope of the commentary by Ghasilal Maharaj:

- Chapter 1: Discusses the nature of dharma (Ahimsa, Samyama, Tapas), including etymological analysis of the word "dharma." It emphasizes the use of a specific mouth-covering (mukha-vastrika) for monks and the importance of "Madhukari" (mendicancy as a bee collects nectar).

- Chapter 2: Focuses on stabilizing the mind of a newly initiated monk in the path of Samyama, featuring a dialogue between Rathnemi and Rajimati, and clarifying who is truly renounced.

- Chapter 3: Outlines the avoidance of fifty-two "Anachirna" (improper practices) that are detrimental to restraint.

- Chapter 4: Connects the avoidance of these "Anachirna" to the protection of the six life-forms (kaya), defining their nature and the importance of "Yatana" (caution) and understanding the non-living (Ajiva) to grasp the path to liberation.

- Chapter 5: Explains that the protection of six life-forms is achieved through pure alms-taking, detailing the proper methods of "Bhiksha" (alms).

- Chapter 6: Describes the eighteen principles that one adheres to through pure alms-taking, emphasizing the importance of truthful and conventional language.

- Chapter 7: Dwells on the four types of language a monk should use, reiterating the need for truth and conventional language.

- Chapter 8: Discusses the treasure of conduct obtained by speaking pure language, detailing the five types of conduct.

- Chapter 9: Explains that adherence to the five types of conduct leads to humility, defining the nature of "Vinaya" (humility).

- Chapter 10: Concludes by defining the true "Bhikshu" (monk) as one who follows the principles laid out in the previous nine chapters.

-

Detailed Discussion on Ahimsa (Page 42-49):

- The text delves into the essence of Ahimsa, defining it as the renunciation of violence and the protection of life. It clarifies that Ahimsa is not merely the absence of violence but also includes the intention and desire to protect living beings. The commentary strongly refutes the idea that Ahimsa is merely passive non-violence, citing scriptural passages where Bhagavan Mahavir actively saved beings like Goshaala through the use of tejas lehya.

- The concept of "Dravya Himsa" (violence through action) and "Bhava Himsa" (violence through intention) is explained. While acknowledging that some forms of Dravya Himsa are unavoidable through careful actions, the focus is on cultivating pure intentions (Bhava Himsa) to avoid karmic bondage. The text provides examples of impurity of intention in the context of actions.

-

Detailed Discussion on Samyama (Page 49-54):

- Samyama is defined as the complete cessation from harmful actions and the control of the mind, speech, and body. It is described as having seventeen divisions, detailing the restraint over the six life-forms (earth, water, fire, air, plants, and sentient beings), and the control of mind, speech, and body.

- The critical importance of the "Mukha-vastrika" (mouth-covering) for monks is extensively argued, drawing parallels from the Bhagavati Sutra where even the divine speech of Indra is deemed impure without it. The commentary refutes arguments against its necessity and emphasizes its role in protecting the subtle life-forms in the air and on one's breath.

-

Detailed Discussion on Tapas (Page 57-63):

- Tapas is explained as the practice that burns away karmic obscurations. It is divided into external (six types) and internal (six types) practices.

- External austerities include Anashan (fasting), Unodari (eating less), Bhikshachari (pure alms-seeking), Rasparityag (renunciation of delicacies), Kayaklesha (physical hardship), and Samlinata (seclusion).

- Internal austerities encompass Prayashchitta (atonement), Vinaya (humility), Vaiyavachchha (service), Swadhyaya (study of scriptures), Dhyana (meditation), and Vyutsarga (renunciation of mental attachments).

- The text argues against the notion that Tapas is merely suffering, explaining it as a means to overcome suffering and achieve liberation. It emphasizes that true Tapas is practiced with pure intention and knowledge, leading to spiritual progress.

-

Examples and Analogies:

- The commentary frequently uses analogies to illustrate Jain principles, such as the bee collecting nectar from flowers without harming them, to explain the principles of pure alms-seeking.

- The text also highlights the distinction between a true renunciate and someone merely afflicted by circumstances, using the example of a person unable to enjoy worldly pleasures due to illness, emphasizing that true renunciation comes from detachment and conscious choice.

- The text uses the example of Rathnemi and Rajimati to illustrate the power of renunciation and the impact of virtuous association.

-

The Importance of Knowledge (Gyan) and Action (Kriya):

- Throughout the text, the author reiterates that knowledge is essential for right action. Pure action (Kriya) stems from right knowledge (Gyan). The emphasis is on understanding the principles of conduct and diligently practicing them.

-

Detailed Guidelines for Monastic Conduct (Achar):

- A significant portion of the text is dedicated to detailing the precise rules of conduct for Jain monks, particularly concerning alms-seeking (Gochari). This includes:

- Acheta-Dravya Grahana: What kinds of food and water are permissible to accept.

- Purva Karma and Paschat Karma: The conduct related to preparing food or items before offering them to a monk and actions taken afterward.

- Specific Prohibitions: Detailed rules about avoiding contact with specific elements or items that are considered impure or likely to cause harm to life-forms, especially during alms-seeking. This includes rules about where to walk, what to touch, and how to interact with the environment.

- Rules on Accepting Food: The text explains the nuances of accepting food, distinguishing between different types of preparations and the conditions under which they are permissible or forbidden. It stresses the importance of examining the food for impurities, proper preparation, and the intention behind its offering.

- Maha-Vratas: The text elaborates on the five great vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism, with a particular focus on Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, and Aparigraha. It explains how these vows are to be practiced in daily monastic life, emphasizing their depth and practical application.

- A significant portion of the text is dedicated to detailing the precise rules of conduct for Jain monks, particularly concerning alms-seeking (Gochari). This includes:

Overall Significance:

The provided text offers a deep dive into the Dasvaikalik Sutra, specifically focusing on the ethical and practical aspects of monastic life within the Shwetambar Sthanakvasi tradition. The commentary by Ghasilal Maharaj is highly regarded for its thoroughness, clarity, and ability to make these ancient teachings accessible to a wide audience. The extensive endorsements from prominent figures attest to the book's authority and value. The detailed explanation of concepts like Ahimsa, Samyama, Tapas, and the rigorous guidelines for alms-seeking and conduct highlight the ascetic discipline integral to Jainism.

Note: The provided pages are primarily introductory, focusing on endorsements and the preface. While they summarize the Dasvaikalik Sutra's structure, the bulk of the content from page 42 onwards is a detailed commentary on specific verses and concepts, particularly Ahimsa, Samyama, Tapas, and the meticulous rules of monastic conduct. The summary above aims to capture the essence of both the introductory material and the philosophical and practical discussions initiated in the initial chapters.