Agam 28 Prakirnak 05 Tandul Vaicharik Sutra

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This is a comprehensive summary of the Jain text, Agam 28 Prakirnak 05 Tandul Vaicharik Sutra, as presented in the provided pages:

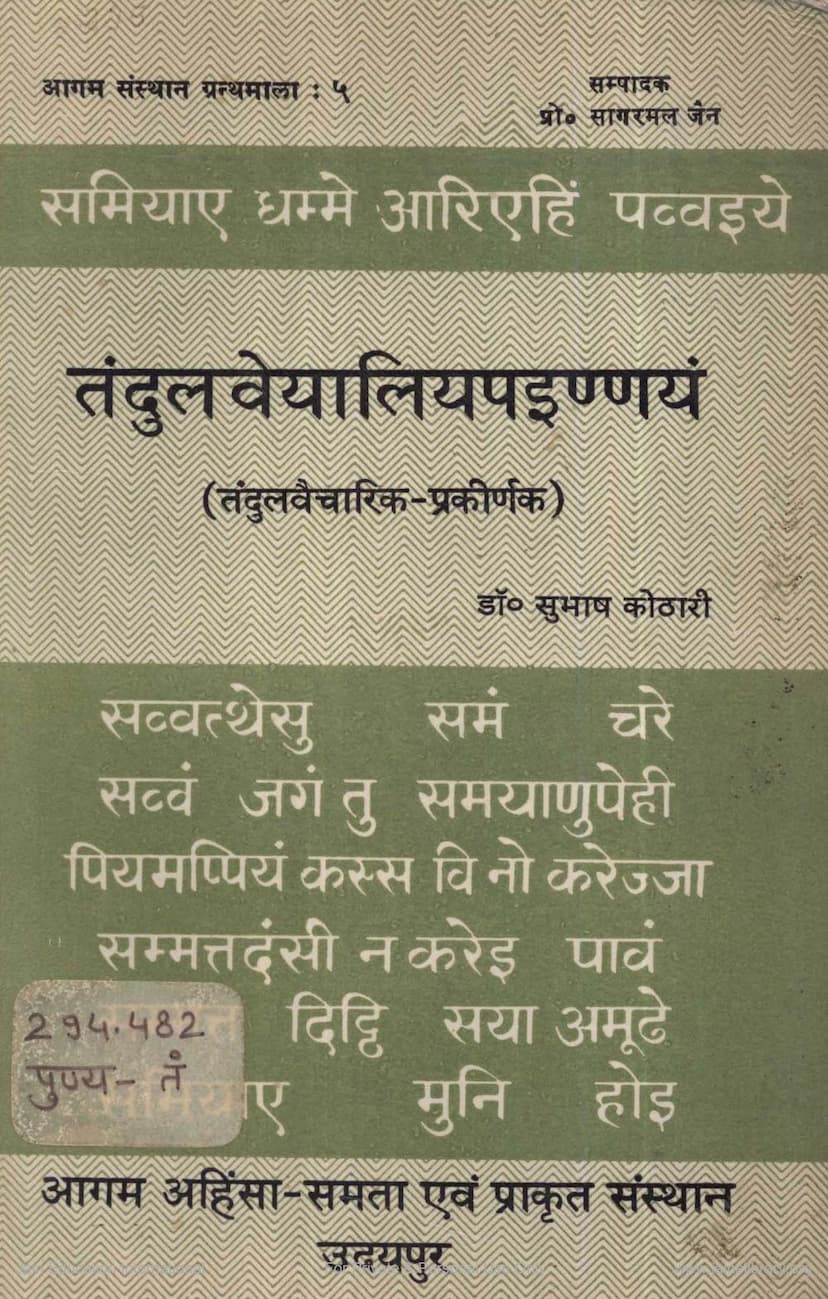

Book Title: Tandulavaicharik Prakirnak (तंदुलवैचारिक-प्रकीर्णक) Author(s): Muni Punyavijay (original text editor), Dr. Subhash Kothari (translator), Prof. Sagarmal Jain, Suresh Sisodiya (contributors) Publisher: Agam Ahimsa Samta Evam Prakrit Sansthan, Udaipur Year of Publication: 1991 (First Edition)

Overall Purpose and Significance:

The "Tandulavaicharik Prakirnak" is a significant Jain Agam text, classified as a Prakirnak (miscellaneous or supplementary text). It delves into various aspects of human life, with a particular focus on spiritual detachment and renunciation. While it discusses biological and temporal matters, its ultimate aim is to inspire vairagya (dispassion) by highlighting the transient, impure, and often repulsive nature of the physical body and worldly existence. The text aims to guide individuals towards righteous conduct and spiritual liberation.

Key Themes and Content:

-

The Nature of Jain Agam Literature:

- Jain Agams are considered the compilation of the teachings of Arhats and Rishis who attained spiritual purity through practice.

- The literature evolved over time, leading to divisions like Ardhamagadhi and Shauraseni Agams.

- Agams are broadly categorized into Angapravishta (based on the twelve Angas) and Angabahya (texts by Shrutakevalins and Purvdharas).

- The Prakirnak category includes texts that are often considered supplementary but are crucial for understanding specific spiritual principles.

-

Classification of Agams and Prakirnak:

- The text details the classification of Agams as found in the Nandi Sutra and Paushadhika Sutra, where Tandulavaicharik is listed under 'Kālika' or 'Utkālika' categories.

- It explains the concept of Prakirnaks as diverse compilations, with a tradition suggesting each monk composed one.

- While ancient texts mention thousands of Prakirnaks, currently, about ten are commonly recognized, including Tandulavaicharik.

-

About the Tandulavaicharik Prakirnak:

- The name "Tandulavaicharik" is explained as a reflection on the calculation of rice grains consumed by a man with a hundred-year lifespan, used as an analogy for life's calculations and impermanence.

- It is a prose-verse mixed composition.

- Its mention in Nandi and Paushadhika Sutras suggests its antiquity, possibly predating the 5th Century CE.

-

Content Breakdown:

-

Mangalavachana (Auspicious Invocation): The text begins with salutations to Lord Mahavir.

-

Impermanent Nature of Life and Calculations: It touches upon the calculation of lifespan, the limited time humans have, and the futility of worldly pursuits.

-

Gestation Period and Embryonic Development:

- Detailed description of the duration of human gestation (approximately 277 days, with variations).

- The formation of the embryo, from the initial 'kalala' (liquid state) to more developed stages within the womb.

- It explains how the fetus derives nourishment through a connection to the mother, emphasizing the internal processes rather than external eating.

- The development of body parts (bones, flesh, senses, etc.) within the womb is described.

-

Formation of Sex and Gestation:

- The conditions leading to the birth of a male, female, or neuter being are discussed, based on the relative strength of paternal semen and maternal ovum.

- It mentions the possibility of a 'Bimba' (a mass of flesh) if conditions are unfavorable.

-

Embryo's Fate (Hell or Heaven):

- The text explains that a fetus dying in the womb can be reborn in hells or heavens, depending on its past karma and any potential actions or desires it might have had.

- It highlights how even a fetus can possess desires and intentions that influence its future birth.

-

Embryo's Symbiotic Existence:

- The fetus experiences sensations and emotions (happiness, sadness) in accordance with the mother's state. It shares her physical movements and bodily functions.

-

Ten Stages of Human Life (for a Centenarian):

- A detailed description of the ten stages of a human life, from infancy to old age, emphasizing the physical and mental changes. These stages are: Bāla (childhood), Krīḍā (play), Mandā (slow/simple), Balā (strong), Prajñā (knowledgeable), Hāyaṇī (declining), Prapañchā (elaborate), Pragmbhārā (decaying), Munmukhī (facing age), and Śayanī (lying down).

- The text uses these stages to illustrate the impermanence of youth and vitality.

-

Age-wise Progression and Consequences:

- It outlines what a human typically achieves or experiences in each decade of life (e.g., learning by 20, enjoyment by 30, wisdom by 40, decline of senses by 50 and 60, etc.).

- It stresses the importance of engaging in Dharma at all stages, especially when life is uncertain and prone to obstacles.

-

Body's Riches (of Ideal Beings):

- It describes the extraordinary physical characteristics (Rddhi) of ideal beings like Yogalikas, Arhats, and Chakravartis, who lived for extremely long periods and possessed divine attributes.

- This serves as a contrast to the frailties of the human body in the current era.

-

Dietary and Temporal Calculations:

- The text provides detailed calculations regarding the lifespan of a centenarian, breaking it down into Yugas, Ayans, Ritus, months, fortnights, days, and nights.

- It meticulously calculates the number of breaths (Uchchvas-Nissvas) within these time periods.

- It estimates the amount of rice grains, wheat, pulses, oil, ghee, and salt consumed by a person throughout their life, illustrating the sheer volume of material existence.

- It also describes the mechanism of a water clock (Ghathika Yantra) for measuring time.

-

Uncertainty of Life and Impermanence (Anityata):

- The text repeatedly emphasizes that life is fleeting, subject to disease, and can end unexpectedly.

- It warns against procrastination in spiritual practice, stating that one never knows when death might strike.

-

The Human Body: Structure and Impurity:

- A detailed, anatomical description of the human body, including bones, veins, nerves, organs, and their functions.

- Crucially, it highlights the impure and repulsive nature of the body, filled with foul substances, secretions, and prone to decay.

- It describes the body as a house of impurities, contrary to its outward appearance. The text uses graphic descriptions to evoke disgust and detachment.

-

The Nature of Women (Strī-Sabhava):

- This is a significant and detailed section. It presents a highly critical and renunciation-oriented view of women.

- Women are depicted as inherently cunning, deceptive, fickle, untrustworthy, prone to anger, treacherous, and the cause of downfall for men.

- Numerous negative epithets and analogies are used to describe their character and influence (e.g., like a serpent, tigress, monkey, poison vine).

- The text emphasizes that a wise person should renounce attachment to women due to these perceived flaws and the transient nature of attraction.

- It notes that the numerous names assigned to women are often based on their deceptive or enslaving qualities.

- The purpose behind this portrayal is to detach men from sensual desires and attachments, which are seen as major impediments to spiritual progress.

-

Moral and Spiritual Guidance:

- The text urges individuals to engage in virtuous deeds (Punya-krit) for positive outcomes in this life and the next.

- It advocates for practicing Dharma (righteousness) consistently, irrespective of one's current state of happiness or sorrow.

- It stresses that true refuge lies in Dharma, which leads to knowledge and ultimately liberation.

-

Critique of Contemporary Society:

- It laments the decline in human physical constitution (strength, longevity, physique) in the current era (Avasarpini Kal).

- It attributes this decline to the increase in negative passions like anger, pride, deceit, and greed.

- It notes the worsening quality of medicines and the increased suffering due to these afflictions.

- It praises those who remain devoted to Dharma amidst such decay.

-

The Call for Renunciation:

- The overarching message is to recognize the impermanence and impurity of the body and world, and to cultivate dispassion.

- It encourages seeking spiritual liberation (Moksha) by following the path shown by the Tirthankaras.

-

Comparative Analysis (as presented in the appendix):

The latter part of the provided text includes a comparative analysis, juxtaposing verses from the Tandulavaicharik with similar verses from other Jain Agams like Bhagavati Sutra, Sthananga Sutra, and Anuyogdvara Sutra. This demonstrates the shared core principles and narrative style within the Jain canonical literature, particularly concerning the stages of gestation and the nature of the body.

In essence, the Tandulavaicharik Prakirnak serves as a potent tool for spiritual instruction, using detailed descriptions of biological processes and societal observations to underscore the ephemeral and impure nature of worldly existence, thereby encouraging detachment and the pursuit of liberation.