Agam 15 Upang 04 Pragnapana Sutra Part 03 Sthanakvasi

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

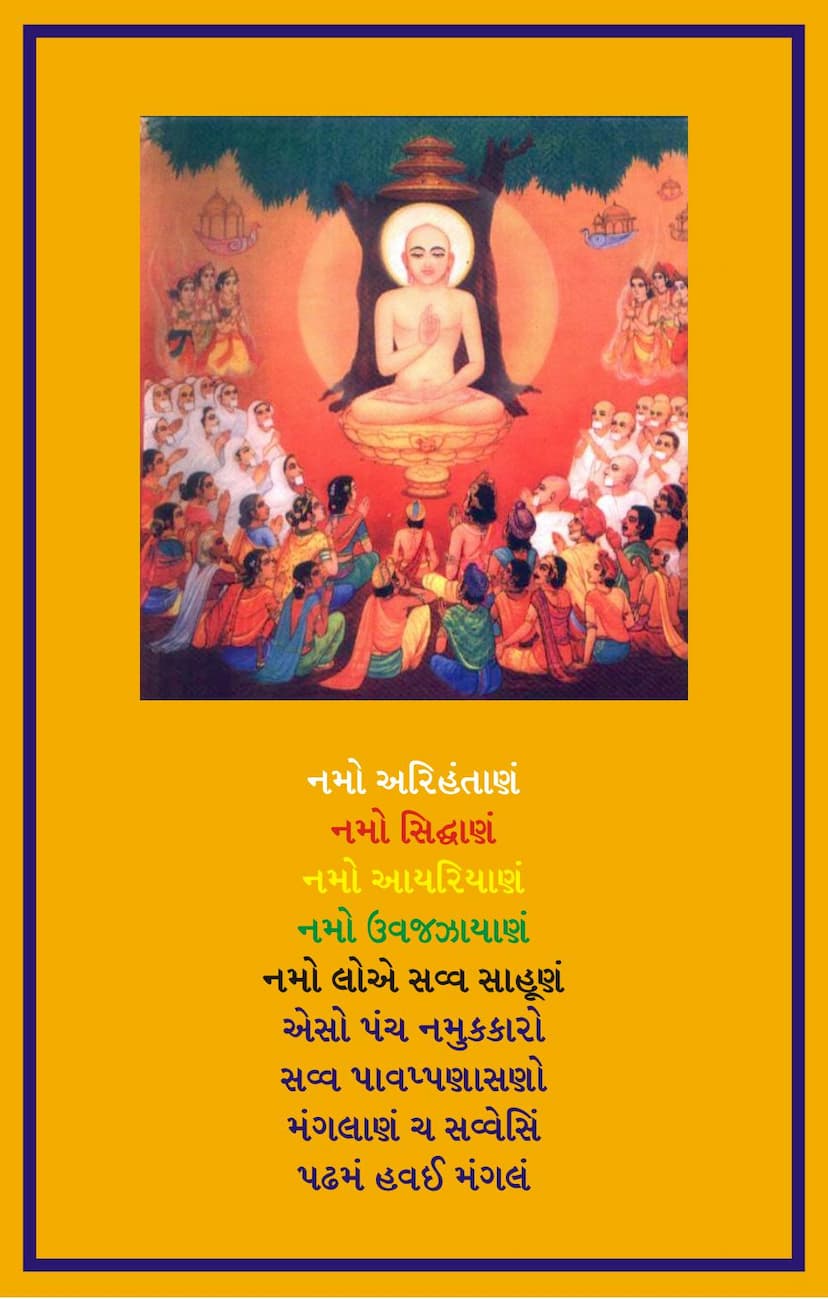

This document is a portion of the Jain text Prajnapanā Sūtra, Part 03, authored by Ghasilal Maharaj and published by A B Shwetambar Sthanakvasi Jain Shastroddhar Samiti. The catalog link provided is https://jainqq.org/explore/006348/1. The text is in Gujarati with Sanskrit shlokas and explanations in Hindi.

The document details the eleventh and twelfth chapters of the Prajnapanā Sūtra, focusing on Language (Bhāṣā) and Body (Śarīra) respectively.

Here's a summary of the key points:

Chapter 11: Language (Bhāṣā)

This chapter discusses various aspects of language, including:

-

Avadhāraṇī Bhāṣā (Language of Comprehension/Certainty): The discussion begins with the concept of Avadhāraṇī Bhāṣā, which is considered the source of understanding or certainty. It is established that this language can be:

- Satyā (Truthful): Language that leads to spiritual well-being, adheres to the teachings of the Omniscient (Arihants), and promotes virtue.

- Mṛṣā (False/Untruthful): Language that deviates from the teachings, causes harm, and leads to spiritual downfall. This is further categorized into types of falsehood stemming from:

- Krodha (Anger)

- Māna (Pride)

- Māyā (Deceit)

- Lobha (Greed)

- Prema (Affection/Attachment)

- Dveṣa (Hatred)

- Hāsya (Laughter/Joking)

- Bhaya (Fear)

- Ākhyāyikā (Storytelling/False Narratives)

- Auopaghātikā (Harmful/Deceptive)

- Satyā-mṛṣā (Truthful-Untruthful/Mixed): Language that contains elements of both truth and falsehood.

- Asatyā-mṛṣā (Untruthful-Untruthful/Unclear): Language that is neither strictly true nor false, often used in practical or conventional contexts (like greetings or general conversation) or when the meaning is unclear.

-

Paryāptikā and Aparyāptikā Bhāṣā (Adequate and Inadequate Language):

- Paryāptikā (Adequate Language): Language that is properly formed and understood. This is further divided into Satyā (truthful) and Mṛṣā (untruthful).

- Satyā (Ten Types): Janapadā-satyā (conventional truth), Sammata-satyā (accepted truth), Sthāpanā-satyā (established truth), Nāma-satyā (nominal truth), Rūpa-satyā (form truth), Pratītya-satyā (relative truth), Vyavahāra-satyā (practical truth), Bhāva-satyā (essential truth), Yoga-satyā (union truth), and Auopamya-satyā (comparison truth).

- Mṛṣā (Ten Types): These are further elaborated as arising from anger, pride, deceit, greed, attachment, hatred, laughter, fear, narratives, and harm.

- Aparyāptikā (Inadequate Language): Language that is not properly formed or understood. This is divided into:

- Satyā-mṛṣā (Mixed): Examples include Upanna-miśritā (newly mixed), Vigata-miśritā (previously mixed), Jīva-miśritā (mixed with living beings), Ajīva-miśritā (mixed with non-living), Ananta-miśritā (infinitely mixed), Pratyeka-miśritā (individually mixed), etc.

- Asatyā-mṛṣā (Unclear/Behavioral): This category includes languages like Āmantraṇī (calling), Ājñāpanī (ordering), Yācanī (asking), Pṛcchanī (inquiring), Prajñapanī (explaining), Pratyākhyānī (renouncing), Icchānulomā (according to desire), Anabhigṛhitā (unqualified), Abhigṛhitā (qualified), Saṁśaya-karaṇī (doubtful), Vyākr̥tā (clear), and Avyākr̥tā (unclear).

- Paryāptikā (Adequate Language): Language that is properly formed and understood. This is further divided into Satyā (truthful) and Mṛṣā (untruthful).

-

Vachana (Grammatical Number): The text also touches upon grammatical number (singular, dual, plural) and its relation to gender (masculine, feminine, neuter), and the usage of these in language.

Chapter 12: Body (Śarīra)

This chapter focuses on the types of bodies and their characteristics, particularly concerning their existence in different realms of existence:

-

Five Types of Bodies: The text identifies five types of bodies:

- Audārika (Gross physical body): The physical body perceptible to gross senses.

- Vaikriyā (Transformable body): A body that can transform and take on different forms.

- Āhārika (Mental body): A body related to mental processes and thoughts.

- Taejas (Luminous body): A body associated with internal radiance or energy.

- Kārmaṇa (Karmic body): The subtle body that carries karmic impressions.

-

Bodies in Different Realms: The text outlines which of these bodies are present in various categories of beings:

- Narakas (Hell Beings): Vaikriyā, Taejas, Kārmaṇa.

- Asura Kumāras to Stanita Kumāras (Lower Celestial Beings): Vaikriyā, Taejas, Kārmaṇa.

- Pṛthivīkāyikas (Earth Elementals) to Chatura Indriyas (Four-sensed Beings): Audārika, Taejas, Kārmaṇa. (Note: Vaikriyā is excluded for Vāyu Kāyikas and others up to Chatura Indriyas).

- Vāyu Kāyikas (Air Elementals): Audārika, Vaikriyā, Taejas, Kārmaṇa.

- Pañcendriya Tiryagyonikas (Five-sensed Animals): Audārika, Vaikriyā, Āhārika, Taejas, Kārmaṇa.

- Manuṣyas (Humans): Audārika, Vaikriyā, Āhārika, Taejas, Kārmaṇa.

- Vānarānta, Jyotiṣka, and Vaimānika Devas (Celestial Beings): Same as Naraka beings (Vaikriyā, Taejas, Kārmaṇa), with variations based on their specific realm and the presence of Āhārika and Audārika for some.

-

Characteristics of Bodies and Their Interactions: The text delves into the nature of these bodies, particularly concerning:

- Charama and Acharama (Extreme and Non-extreme): This concept is explored in relation to substances like atoms and conglomerates of atoms (skandhas) and their existence within space. It discusses how some things are limited (extreme) and others are not (non-extreme), and how this applies to different substances and their parts.

- Substance vs. Spatial Extent: The text differentiates between the substance of a thing and its spatial extent (number of points occupied in space).

- Formation and Dissolution of Language: The process of language formation and dissolution is described, linking it to the interaction of karmaṇa bodies and the subtle energies involved. The concept of dharmāstikāya (extension substance) and its role in the propagation of language is also touched upon.

- Atomicity and Aggregates: The discussion on charama and acharama leads to the concept of atoms (paramāṇu) and the aggregates formed by them (skandha), analyzing their potential for being extreme, non-extreme, or inexpressible.

-

Types of Formation (Saṁsthāna): The text categorizes the forms or structures of substances, including:

- Parimaṇḍala (Circular)

- Vṛtta (Round)

- Tryasra (Triangular)

- Chaturaśra (Square)

- Āyata (Rectangular/Elongated)

-

Alpa-Bahutva (Less-Muchness): For each of these formations, the text analyzes the alpa-bahutva (comparative quantity) in terms of substance, spatial extent, and a combination of both, considering whether they are infinite, innumerable, or countable.

The provided text focuses on the initial parts of these chapters, outlining definitions and basic classifications. The complexity arises in the later sections, which go into detailed philosophical and cosmological discussions. The text highlights the Jain view on the nature of reality, consciousness, language, and the subtle composition of beings and the universe.