Agam 15 Upang 04 Pragnapana Sutra Part 03 Sthanakvasi Gujarati

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This comprehensive summary synthesizes the provided text from the Pragnapana Sutra, Part 03, focusing on the Jain Sthanakvasi Gujarati edition. The text elaborates on various aspects of Jain philosophy, particularly concerning the nature of existence, the cycle of rebirth, and the classification of beings.

Here's a breakdown of the key themes and concepts discussed in the provided pages:

1. Foundational Jain Principles (Pages 1-4):

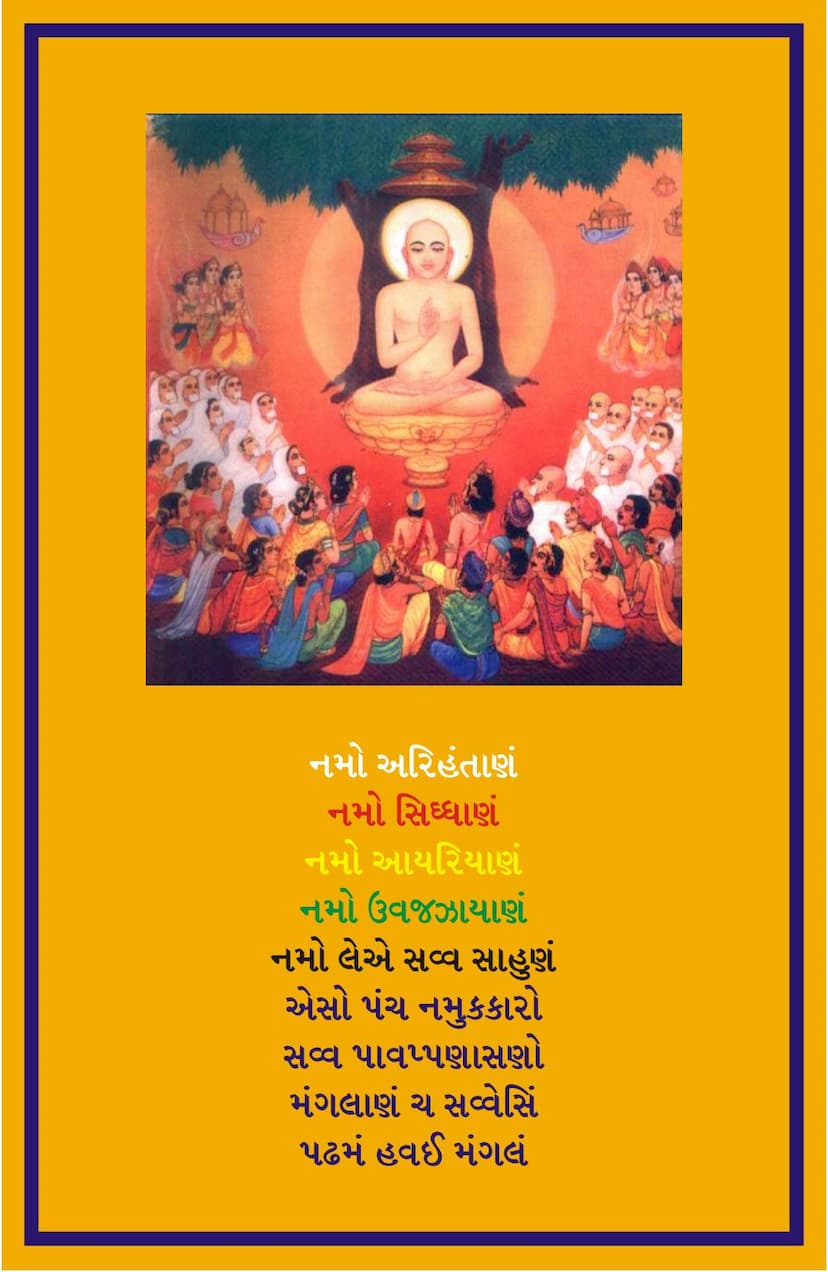

- Invocation: The text begins with the traditional Jain invocation, "Namo Arihantanam, Namo Siddhānam, Namo Āyariyānam, Namo Uvajjhāyānam, Namo Loye Savva Sāhūnam," highlighting the reverence for the Arihants, Siddhas, Acharyas, Upadhyayas, and all Sadhus. The "Panch Namukaro" mantra is presented as the destroyer of all sins and the greatest auspiciousness.

- Context and Authorship: It identifies the book as "Agam 15 Upang 04 Pragnapana Sutra Part 03," authored by Ghasilal Maharaj, published by A B Shwetambar Sthanakvasi Jain Shastroddhar Samiti. The catalog link and personal use disclaimer are also noted.

- Editorial and Publication Details: Pages 2-4 provide further details about the publication, including the Gujarati edition, the organizer (Shri Chandra P. Doshi), the author's commentary ("Prameyabodhini"), Hindi and Gujarati translations, and the publishing committee (Shri Shantilal Mangaldas Mai). It also lists the edition details (first printing, 1200 copies, Veer Samvat 2503, Vikram Samvat 2033, corresponding to 1977 CE) and the price.

2. Rules for Studying the Sutra (Pages 5-9):

- Appropriate Times for Study: The text specifies times for studying the original text (Mool Path): the first and fourth quarters of the day and night. Specific times are prohibited: dawn, dusk, noon, and midnight for periods of two ghadis (48 minutes). It also mentions specific durations before and after sunrise when study is not allowed.

- Restrictions for Women: Women observing monthly menstruation are prohibited from studying the text or being in the same room during study.

- 32 Instances of "Aswadhyaya" (Prohibited Study Times): A significant portion details 32 specific circumstances when study is forbidden. These are categorized into:

- 10 Celestial Phenomena (Akash Sambandhi): Falling stars (Ulka-paat), directional burning (Dig-dah), frightening thunder (Garjarav), divine sounds (Nirdhaat), lightning (Vidyut), specific twilight conditions (Yupak), celestial radiance (Yakshadipt), dark fog (Dhumika Krishna), white fog (Mahika Shwet), and dust storms (Raj-uddhaat). The duration of prohibition varies for each phenomenon.

- 10 Related to the Physical Body (Audarik Sharir Sambandhi): Burning of bones, flesh, and blood; broken eggs; visible excreta and urine with bad odor; crematorium sites (100 hath radius); lunar and solar eclipses (with varying durations); royal turmoil or unrest; death of a king or important person until funeral rites and succession; and fallen dead bodies (within 100 hath of the dwelling).

- 8 Occasions Related to Festivals and specific Days: Four major festivals (Bhoot Mahotsav, Indra Mahotsav, Skandh Mahotsav, Yaksha Mahotsav) and the four days following them (Pratipada).

- 2 Specific Times of Day: Reddish directions in the morning and evening (one ghadi before/after sunrise/sunset) and two ghadis around midday and midnight.

- Distinction for Translations: Crucially, the text clarifies that these Aswadhyaya rules are for the Mool Path only and not for translations in Gujarati or other languages. It emphasizes that reverence (Vinay) is the foundation of Dharma and that in difficult situations, one should follow the wishes of elders or the Guru.

3. Detailed Content Overview (Pages 10-46): The provided pages offer a chapter-by-chapter breakdown of the Pragnapana Sutra (likely referring to its contents rather than the study rules). The summary of the book's sections reveals its profound and systematic approach to understanding Jain cosmology, karma, and the nature of souls and their experiences.

The text covers at least 16 major sections (Pata) with numerous sub-sections, detailing topics such as:

- Naraka (Hellish Beings): Their respiration cycles (Uchchwas-Nishwas).

- Sentience (Sanjna): The ten types of sentience (food, fear, sex, possession, anger, pride, deceit, greed, worldliness, and 'Ogha' - general awareness) and their prevalence across different classes of beings (Naraka, Asura Kumar, etc., up to Vaimanika).

- Yoni (Wombs/Origin of Birth): The classification of birth places or origins based on temperature (hot, cold, or mixed) and their distribution across different realms. It also details the states of conception (Yoni) as animate (Sachitta), inanimate (Achitta), or mixed (Mishra).

- Charam-Acharam (Terminal and Non-terminal aspects): The analysis of the Charam (last/terminal) and Acharam (non-terminal/intermediate) aspects of existence, including their distribution in the cosmos, from hellish realms to the uppermost heavens and beyond. This section delves into how elements or locations are described in terms of being terminal or intermediate.

- Usage of Language (Bhasha): The text discusses the nature of language, classifying it into four types: truthful (Satya), false (Mrusha), mixed truth-falsehood (Satyāmrūshā), and falsehood-indescribable (Asatyāmrūshā). It also categorizes language by its intention (fearful, instructive, etc.) and by gender (masculine, feminine, neuter).

- Life Processes (Prāṇāpāna/Bhasha): Detailed discussion on the breathing cycles (Prāṇāpāna) of various beings, from hellish beings to celestial beings, specifying the duration between breaths. It also covers the use of language and its nuances.

- Physical Manifestations (Shareer): The five types of bodies (Audārika, Vaikriyaka, Āhārakaka, Taijasa, and Kārmaṇa) and their distribution across different species. It also details the Baddha (bound) and Mukta (free) aspects of these bodies.

- Sense Perceptions (Indriya): The number, form, dimensions (Pradesh), location (Avagahana), and qualities (rough/smooth, soft/hard) of the five senses.

- Prashamana/Upashama (Pacification of Karma): The text touches upon the pacification of passions and their impact.

- Usage (Prayog): The study analyzes the manifestation of activities related to the senses and mind, including mental, verbal, and physical actions, as well as the role of different types of bodies in these actions.

- Scriptural Classification (Sthāpnā): The text discusses Sthāpnā (imposition or arrangement), which involves classifying entities based on their perceived form or location.

- The Nature of Jiva and Ajiva (Jiva Prayog): Explores the different states and activities of souls (Jiva) and non-souls (Ajiva), including their relation to karma and liberation.

4. Detailed Discussion on Specific Topics (Pages 13-46): The later pages dive deeper into specific topics, illustrating the comprehensive nature of the Pragnapana Sutra:

- Respiration Cycles (Uchchvas-Nishwas): Detailed calculation of breathing intervals for various celestial beings, linking it to their lifespan and enjoyments.

- Sentience (Sanjna): Analyzing the intensity and prevalence of the ten sentiences across different life forms, from Naraka to Devas.

- Types of Yoni (Wombs/Origin): Discussing the Yoni based on temperature (hot, cold, mixed) and its relation to the origin of beings, including the animate (Sachitta), inanimate (Achitta), and mixed states.

- Charam-Acharam (Terminality): A complex discussion on the terminal and non-terminal aspects of places, beings, and entities within the Jain cosmology, particularly focusing on how these concepts apply to different parts of the universe.

- Language (Bhasha): The different classifications of language, including Satya (truthful), Mrusha (false), Satyāmrūshā (mixed), and Asatyāmrūshā (unutterable/conventional). It examines the conditions under which language is considered truthful or false, and the role of intention and context.

- Types of Prayog (Usage/Activity): Categorizing activities into mental, verbal, and bodily actions, and their further subdivisions, including the connection to different types of bodies (Audārika, Vaikriyaka, etc.).

- The Role of Indriyas (Senses): Detailing the nature, size, location, and qualities of the five senses and how they interact with the external world. It also discusses the concept of Aswadhyaya (prohibited study times) and the specific conditions under which study should be avoided.

- The Concept of Vachana (Speech/Grammar): Analyzing the classification of speech into grammatical categories like singular, dual, plural, and gender-specific.

- The Classification of Jiva (Soul) and Ajiva (Non-soul): Exploring the distinct states and activities of souls and non-souls, and how Prayog (activity) relates to them.

- The Nature of Karma and its Manifestations: Briefly touching upon the types of karma (knowledge-obscuring, perception-obscuring, feeling, delusion, lifespan, name, body, and obstruction) and their influence on kashayas (passions).

- The Concept of Parinamana (Transformation/Modification): Describing the ten types of transformations in souls, such as Gati (motion), Indriya (sense organs), Kashaya (passions), Leshya (aura), Yoga (activity), Upayoga (consciousness/application), Jnana (knowledge), Darshana (perception), Charitra (conduct), and Veda (feeling/emotion).

- The Aswadhyaya rules are particularly detailed, emphasizing the importance of reverence and proper conduct during spiritual study.

Overall Significance:

The Pragnapana Sutra, as presented in this excerpt, is a foundational text in Jainism, offering a highly analytical and philosophical framework for understanding the universe and the soul's journey. The detailed classification of beings, their physical and spiritual attributes, the conditions affecting spiritual practice, and the subtle distinctions in language and consciousness highlight the depth and rigor of Jain thought. The inclusion of specific rules for study underscores the text's practical application within the Sthanakvasi tradition. The commentary by Ghasilal Maharaj aims to elucidate these complex concepts for contemporary readers.