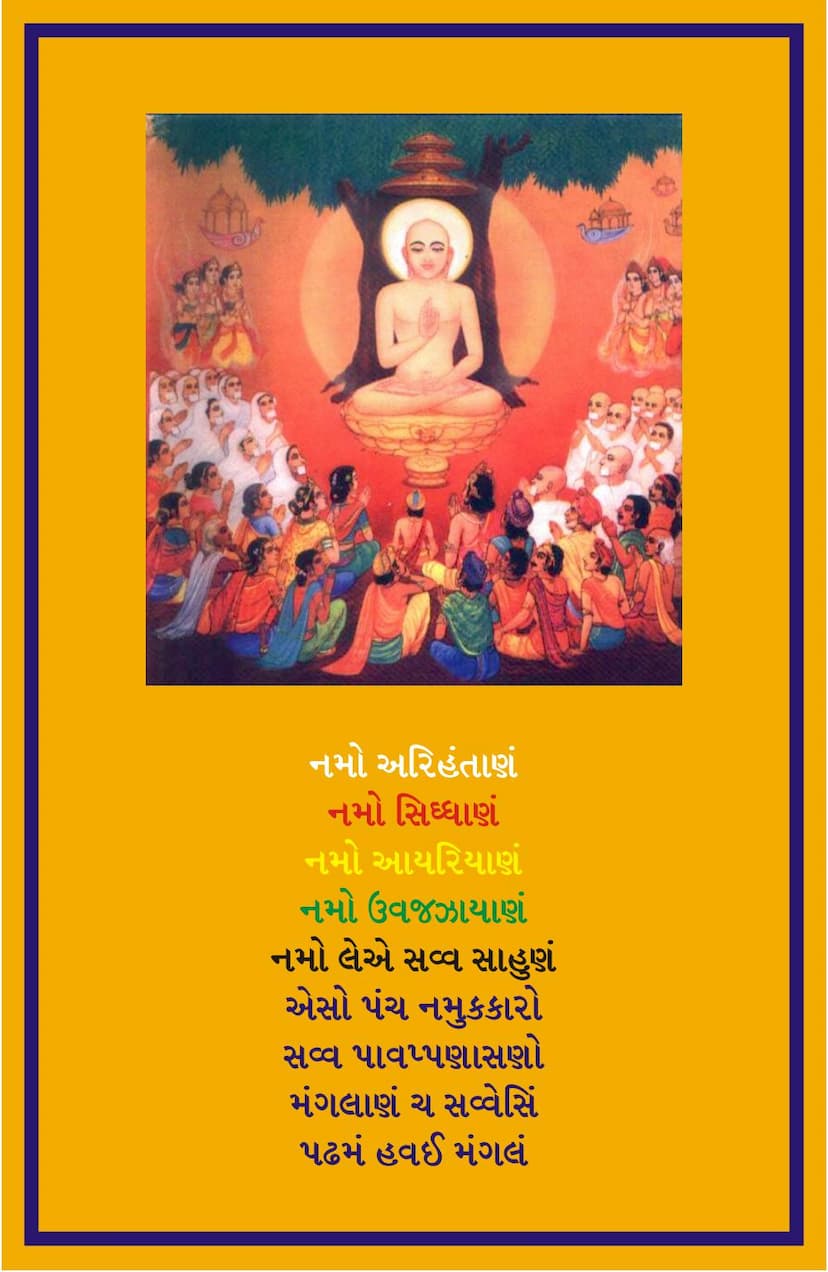

Agam 15 Upang 04 Pragnapana Sutra Part 02 Sthanakvasi Gujarati

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here is a comprehensive summary in English of the provided Jain text, "Agam 15 Upang 04 Pragnapana Sutra Part 02 Sthanakvasi Gujarati" by Ghasilal Maharaj, based on the provided pages:

Overall Context:

The provided text is Part 2 of the Pragnapana Sutra, a significant Jain scripture. This volume focuses on detailed classifications and analyses within the Jain cosmological and ethical framework, particularly concerning the nature and distribution of sentient beings (jivas) and their characteristics across different realms and life forms. The text is presented in Gujarati with Sanskrit headings and explanations, indicating a commentary or translation by Ghasilal Maharaj. It is published by the Akhil Bharat Shwetambar Sthanakvasi Jain Shastroddhara Samiti.

Key Sections and Themes:

The provided pages cover several chapters or "pads" (સ્થાન) of the Pragnapana Sutra, each exploring a different aspect of Jain philosophy. The central theme is the comparative analysis of the number of souls (jivas) or their characteristics based on various criteria, such as:

-

Directional Analysis (દિશાના અનુપાત): Pages 14-23 discuss the relative abundance of different types of souls (e.g., different life forms, hell-dwellers, gods) in different directions (East, West, North, South) and locations within the universe (e.g., Meru mountains, oceans, specific realms). It explains how factors like water availability, presence of specific dwelling places (like Narakaavas), and divine abodes influence the distribution of souls.

-

Movement Analysis (ગતિદ્વાર): Pages 30-32 explore the relative numbers of souls in different modes of existence or transmigration (gati) – hell-dwellers (naraka), animals/lower beings (tiryanchan yoniki), humans (manushya), gods (deva), and souls in liberation (siddha). It establishes a hierarchy of their numbers, generally showing liberation (siddha) and beings in the higher heavens (devs) as less numerous than hell-dwellers, with humans being particularly scarce.

-

Sensory Analysis (સેન્દ્રિય છવો): Pages 32-37 analyze the relative numbers of souls based on their sensory faculties (one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed, and five-sensed beings). It also delves into the comparison between perishable (aparyapta) and non-perishable (paryapta) beings within each category. The text generally indicates that higher the sensory faculty, the fewer the beings, with the exception of the supreme one-sensed beings (Nigoda), which are described as infinite.

-

Life-Form/Body Type Analysis (કાયદ્વાર): Pages 37-45 discuss the relative numbers of souls based on their life-form or body type (kaya). This includes earth-bodied (prithvikaya), water-bodied (apkay), fire-bodied (tejkaya), air-bodied (vayukaya), plant-bodied (vanaspatikaya), and beings with multiple senses or mind (trasakaya). It explains the vastness of one-sensed beings, especially plant-bodied (vanaspatikaya) and Nigoda (a specific type of one-sensed beings), in contrast to the relatively fewertrasakaya beings. It also differentiates between the perishing (aparyapta) and non-perishing (paryapta) forms within these categories.

-

Subtle vs. Gross Analysis (સૂક્ષ્મ મેં આરા): Pages 45-52 compare the numbers of subtle (sukshma) and gross (badar) beings across various categories (e.g., subtle fire-bodied vs. gross fire-bodied, subtle plant-bodied vs. gross plant-bodied). It establishes that subtle beings, especially in their perishing form, are generally fewer than gross beings, with the exception of subtle beings in their non-perishing form, which are described as vast.

-

General Classification of Souls (જીવ): Pages 52-55 continue the comparison of subtle and gross beings, further categorizing them into different life forms and their perishing/non-perishing states. The text reiterates the vastness of certain categories, particularly plant-bodied beings and the overall concept of 'souls' (jivas) as being more numerous due to their pervasive nature.

-

Time-Based Analysis (સ્થિતિ): Pages 67-84 detail the lifespans (sthiti) of various beings, starting from hell-dwellers (naraka) and progressing through various classes of gods. It provides specific ranges for their existence, distinguishing between perishing (aparyapta) and non-perishing (paryapta) states. This section highlights the immense lifespans of higher gods compared to hell-dwellers and humans.

-

Causality and Origin Analysis (ઉપપાત): Pages 340-398 delve into the concept of 'upapata' (birth/creation in a new life form) and 'udvartana' (leaving one form for another). It meticulously explains the origin of souls in different realms (hell, animal, human, and divine) and their subsequent states, categorizing them by the types of beings they are born from (e.g., hell-dwellers are not born from gods, but from other hell-dwellers, tiryanchan yoniki, and humans). It also details the specific conditions and preceding life forms from which each category of being originates.

-

Specific Life Form Origin Analysis: The text further breaks down the origins of various life forms, including hell-dwellers from specific realms and states, the relative numbers of beings in different directions and realms, and the prevalence of beings with particular sensory faculties or body types.

Methodology and Key Concepts:

The text employs a highly analytical and quantitative approach, often comparing the numbers of souls based on:

-

Numerical Comparison (અલ્પબહુત્વ): The core of many sections is to establish the relative quantities of different categories of souls. This is expressed using terms like "fewer" (alp), "more" (bahutva), "equal" (tulya), and "special" or "more than much" (vishesh). The text often uses concepts like "ananta" (infinite) and "asankhyeya" (innumerable) to describe the vast quantities of certain life forms.

-

Categorization: Souls are meticulously categorized based on their life-form (ekendriya, dvindriya, indriya, chaturindriya, pañcendriya), their origin (gati), their sensory faculties, their lifespan (sthiti), their karma (leshya, kashaya), their spiritual state (samyagdarshana, mithyadarshana), their knowledge (jnana), and their physical attributes (varna, gandha, rasa, sparsha).

-

Causality and Transformation (Karma): Jain philosophy emphasizes karma's role in transmigration. The text implicitly touches upon this by discussing how beings transition between different life forms and realms, influenced by their past actions and the remaining lifespan (ayu).

-

Cosmic Structure: The analysis is framed within the Jain understanding of the universe, with references to different realms (lok), directions, and regions of the cosmos.

Publisher and Author:

- Author: P.P. Acharya Shri Ghanshilalji Maharaj (p.p. ācāryaśrī ghāṁsīlāl jī mahārāja)

- Publisher: Shri Akhil Bharat S.S. Jain Shastroddhara Samiti, Rajkot, Saurashtra, W. Ry, India.

- Commentary: Ghasilal Maharaj Krut Vyakhya Sahit (with commentary by Ghasilal Maharaj).

- Language: Gujarati (with Sanskrit headings).

Overall Significance:

This part of the Pragnapana Sutra provides a detailed and intricate understanding of the Jain worldview concerning the distribution and characteristics of souls. It serves as a foundational text for comprehending Jain cosmology, the cycle of birth and death, and the immense diversity of life forms within the Jain universe. The detailed numerical comparisons and categorizations are crucial for understanding the Jain emphasis on the subtle differences and relationships between all forms of existence.