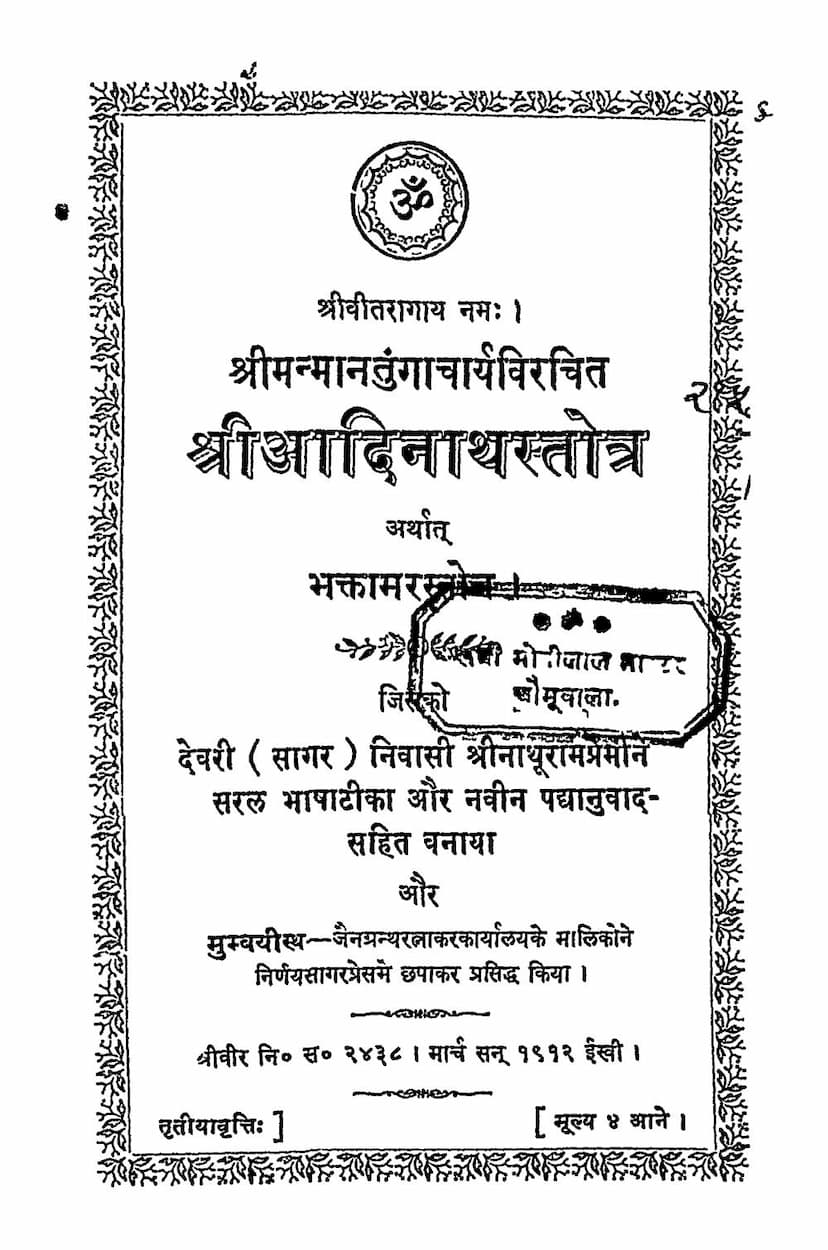

Adinath Stotra Arthat Bhaktamar Stotra

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

This document is the Hindi translation and commentary of the Adinath Stotra, also known as the Bhaktamar Stotra, authored by Shrimad Manatungacharya. The edition presented here is by Nathuram Premi, published by Shri Jain Granth Ratnakar Karyalaya in Bombay in March 1912.

Here's a comprehensive summary based on the provided pages:

Introduction (Pages 3-6):

- Significance of the Stotra: The introduction emphasizes the immense importance and widespread recitation of the Bhaktamar Stotra within the Jain community. It states that many Jains do not eat without reciting it or the Tattvartha Sutra, and a Jain child is not considered educated until they can read the "Bhaktamar Sutra."

- Purpose of the Translation: The author, Nathuram Premi, expresses regret that due to a lack of Sanskrit knowledge in the current society, people are unable to appreciate the profound virtues and "nectar" within the original text, which even scholars of other religions admire. This translation aims to make that "nectar" accessible to those unfamiliar with Sanskrit.

- Challenges of Translation: The author acknowledges the difficulty in perfectly conveying the rasa (flavor) and anand (joy) of the Sanskrit verses into Hindi. However, he has strived to ensure that the essence of each original verse is retained.

- Previous Works and the Need for This Edition: The author notes that no prior commentary on the Bhaktamar Stotra was available that was truly accessible to students and the general public. While a Gujarati translation with a Hindi explanation existed, it was merely a "meaning" and not a true commentary. This edition aims to fill that gap.

- Comparison with Hemrajji's Translation: The author addresses a potential question about the necessity of a new poetic translation when Pandit Hemrajji's exists. He quotes Amitagati Acharya to argue that new poetry can be as valuable as old. While acknowledging Hemrajji's translation as beautiful and possessing clarity, he points out that it is an independent translation that captures the "sense" rather than adhering closely to every word and verse. He gives an example of the 37th verse where the translation, while good, doesn't fully capture the nuance of the original. He also criticizes Hemrajji's use of the Chaupai meter as restrictive, leading to complex and sometimes meaning-deviating translations, as seen in his rendition of the 9th verse.

- Goal of the New Translation: The author's long-held desire was to create a translation that is a "true replica" of the original, while also being simple, easy to read, and quickly understandable. He acknowledges that despite his efforts to simplify, the inherent difficulty of Sanskrit concepts has made some parts challenging.

- Humility and Intent: Premi expresses humility about his poetic abilities, stating he doesn't expect readers to solely read his translation out of pride in his poetry. His sole aim is to clearly explain the complete meanings of the original text.

- Acknowledgements: The author concludes by thanking his scholarly friends who assisted in the review and revision of the work.

Historical Account of Shrimad Manatungacharya (Pages 7-15):

This section provides a biographical narrative of Shrimad Manatungacharya, which is intertwined with the origin of the Bhaktamar Stotra.

- The Story of Durshasa and Kalidasa: The narrative begins with the story of Vararuchi, a scholar in King Bhoj's court, and his daughter Brahmadevi. Brahmadevi's marriage to the foolish Durshasa (whom Vararuchi married off in anger) is described. Durshasa's ignorance and inability to learn are highlighted.

- Durshasa's Transformation: Out of shame after being publicly humiliated by Vararuchi, Durshasa seeks the blessings of the goddess Kalika. He is granted the boon of "Vachansiddhi" (power of speech) and becomes the renowned poet Kalidasa.

- The Debate with Dhananjaya: Kalidasa, now a celebrated poet, encounters Dhananjaya, who authored the "Namamala" (later called "Namamanjari"). Kalidasa belittles Dhananjaya's work, claiming it's not suitable for a merchant to compose such texts. This leads to a debate, and Dhananjaya challenges Kalidasa to debate his guru, Manatungacharya.

- Manatungacharya's Summoning: King Bhoj, intrigued by the dispute, summons Manatungacharya. Manatungacharya initially refuses to come, stating he doesn't engage in worldly affairs. Despite multiple attempts by the king's messengers, he remains firm.

- Imprisonment and the Bhaktamar Stotra: Angered by Manatungacharya's refusal, King Bhoj has him arrested and imprisoned. After three days of captivity, Manatungacharya composes the Adinath Stotra (Bhaktamar Stotra). Upon reciting it, the chains and locks break, and he is freed. He is recaptured, but the stotra repeatedly breaks his bonds.

- The Miracle and Resolution: The king witnesses this miracle. Kalidasa then invokes Kalika, while Manatungacharya invokes Chakreshwari Devi. Chakreshwari defeats Kalika, who repents and vows to cease causing harm.

- King Bhoj's Conversion: Impressed by Manatungacharya's spiritual power and the events, King Bhoj accepts Jainism and becomes a lay follower (Shravaka).

- Historical Context and Discrepancies: The document notes that this story is based on a Sanskrit commentary by Bhattaraka Vishwabhushan. It discusses the historical placement of Manatungacharya, suggesting he was contemporary with King Bhoj of Ujjain (11th century CE). However, it also presents differing historical views:

- Some Digambara texts have different accounts of Manatunga.

- A Shvetambara tradition also exists.

- Historian Pt. Gaurishankar Hirachand Ojha places Manatunga during the time of Shri Harsha (607 CE), about 400 years before Bhoj.

- Prabhachandra Suri, commentator of the Bhaktamar, states Manatunga was initially a Buddhist and composed the stotra after his guru's instruction, suggesting it wasn't written to escape prison.

- The document concludes that Manatunga's history and time are somewhat obscured, and the presented story is for its narrative appeal and prevalence, especially for children.

- Shvetambara Tradition: It's mentioned that the Shvetambara tradition also widely uses the Bhaktamar Stotra but considers it to have 40 verses instead of 48.

The Stotra's Verses (Pages 15-67):

The document then presents the original Sanskrit verses of the Stotra, followed by a Hindi translation and commentary for each verse. The verses describe the glory of Lord Adinath (Rishabhadeva), the first Tirthankara, highlighting his attributes, the power of devotion, and the miraculous protection offered by reciting his praise.

Key themes and descriptions in the verses include:

- Praise of Adinath's Feet: The first verses glorify the lotus feet of Adinath, which are worshipped by gods and serve as a refuge for those suffering in the cycle of birth and death.

- Inability of the Poet: The poet expresses his inadequacy to fully describe the Lord's infinite virtues, comparing himself to a child trying to grasp the reflection of the moon in water or someone trying to swim across an ocean.

- Power of Devotion: Despite his limitations, the poet is driven to praise by devotion, likening himself to a doe protecting its fawn from a lion.

- The Stotra's Efficacy: The verses detail the stotra's ability to destroy sins, remove suffering, and grant liberation.

- Comparison to Natural Phenomena: Adinath's qualities are often compared to natural elements like the sun, moon, jewels, and lotuses to illustrate his unparalleled brilliance, purity, and auspiciousness.

- Protection from Dangers: Many verses describe how the recitation of the stotra protects devotees from various dangers like wild animals (elephants, lions, snakes), fires, floods, sea voyages, imprisonment, and even diseases like dropsy.

- Eighteen Miraculous Signs (Pratiharyas): The stotra describes several auspicious signs or miracles associated with the Tirthankaras, such as the presence of the Ashok tree, the jeweled throne, the white parasols, the celestial music, the divine showering of flowers, the radiant halo, and the celestial voice (Divya Dhwani).

- The Tirthankara as the Ultimate Guide: The verses firmly establish the Tirthankara as the true Buddha, Shankar, Brahma, and Purushottam, surpassing all other deities in spiritual realization and efficacy.

- The Power of the Name: The inherent power of remembering the Lord's name is emphasized repeatedly as a means of protection and liberation.

- The Fruit of Recitation: The concluding verses promise that whoever recites this stotra with devotion will be blessed with prosperity, power, and ultimately, liberation.

Author's Prayer (Pages 68-69):

The document concludes with a short prayer from the translator, Nathuram Premi, expressing his humility regarding any shortcomings in the translation and asking for the blessings of scholars and discerning readers to correct any errors.

In essence, the document provides a devotional and historical perspective on the Bhaktamar Stotra, making its profound teachings and miraculous accounts accessible to a wider Hindi-speaking audience.