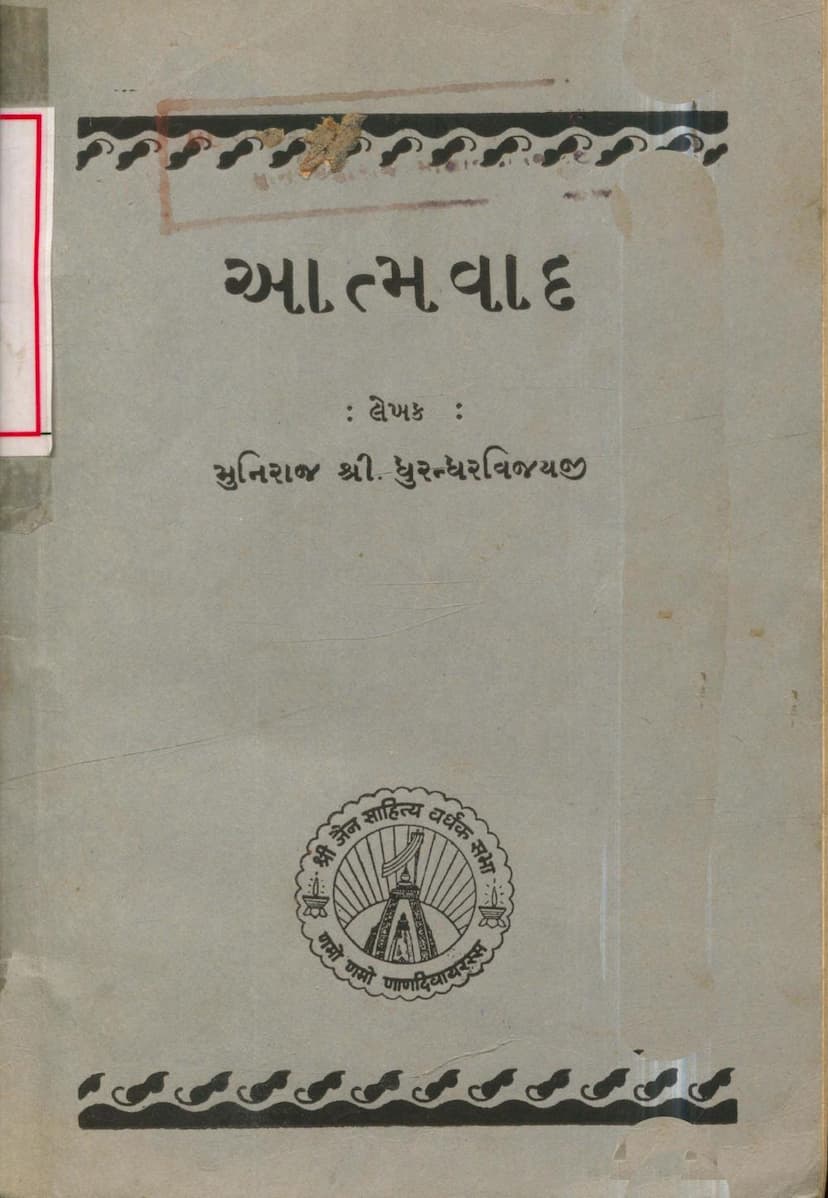

Aatmvad

Added to library: September 1, 2025

Summary

Here's a comprehensive summary of the Jain text "Aatmvad" by Dhurandharvijay, based on the provided pages:

Book Title: Aatmvad (On the Nature of the Soul) Author: Muni Shri Dhurandharvijayji Publisher: Jain Sahityavardhak Sabha, Bhavnagar Publication Year: Vikram Samvat 2003 (1947 CE) / Vir Nirvana Samvat 2473

Overall Purpose:

"Aatmvad" is a Jain philosophical text that aims to establish the existence and nature of the soul (Atma) by refuting various non-Jain perspectives and presenting the Jain viewpoint. It engages in dialogue and reasoned arguments to demonstrate the validity of the Jain understanding of the soul.

Key Chapters and Content:

The book appears to be structured into several chapters, each addressing different philosophical schools and their views on the soul:

Chapter 1: Aatmasiddhi (Establishment of the Soul)

-

Introduction of the Debate: The chapter begins by highlighting the diverse and often contradictory views on the soul held by different philosophical schools:

- Charvakas: Deny the existence of a soul.

- Buddhists: Consider the soul as momentary and a stream of consciousness.

- Vedantins: View the soul as eternally unchanging and purely consciousness.

- Nyaya: Believe the soul is all-pervading, becomes inert when liberated, and is dependent on the Supreme Soul (Parmatma).

- Samkhya: Describe the soul as eternal and unchanging.

- The text states that all these views are flawed, and the Syadvada (Jain doctrine of conditional predication) will explain their flaws and present the pure nature of the soul.

-

The Keshi-Pradeshi Dialogue: This is the central narrative of the chapter, illustrating the existence of the soul through a compelling conversation between King Pradeshi and Acharya Keshi.

- Setting: The story takes place in Shvetambika, ruled by the atheistic King Pradeshi, who is influenced by his minister Chitra. Acharya Keshi, a Jain Ganadhara (chief disciple of Tirthankara), is present in India.

- The Encounter: Acharya Keshi arrives in Shravasti, where Minister Chitra, visiting for state work, encounters him. Impressed by the Acharya's wisdom, Chitra accepts the teachings of right faith (samyaktva).

- Chitra's Plan: Minister Chitra, wanting his king to also embrace the righteous path, requests Acharya Keshi to visit Shvetambika. He cleverly devises a plan to bring King Pradeshi to meet the Acharya. He suggests an excursion to the royal garden, leading the king to where Acharya Keshi is discoursing.

- King Pradeshi's Atheistic Arguments: Upon seeing Acharya Keshi, the king dismisses him as a beggar and a deceiver. He then presents his arguments for the non-existence of the soul:

- Parental Testimony: After his mother (religious) and father (atheistic) died, neither returned to guide him, leading him to believe in neither heaven nor hell, nor the soul.

- Physical Experiments: He describes experiments where he dissected a living thief, weighed a living thief and then its corpse (finding no weight difference), and enclosed a thief in a sealed box which later contained only a corpse. In all cases, he found no evidence of a soul, concluding its non-existence.

- Five Elements Theory: He explains that actions like speaking and walking are merely the result of the combination of the five elements (earth, water, fire, air, space) and not an independent soul.

- Acharya Keshi's Refutations: Acharya Keshi systematically refutes the king's arguments:

- Parental Testimony: He uses an analogy of a rich person promising to help a beggar but being unable to fulfill it due to circumstances to explain why the parents might not have returned. He also describes the nature of heavens and hells and the limited presence of gods in the human realm, suggesting other reasons for their absence.

- Soul as Non-Physical: He explains that just as wind is not visible but can be perceived through its effects, the soul, being non-physical, cannot be perceived by the senses but can be understood through the mind and inference.

- Experiments with the Soul: He criticizes the king's destructive methods, stating that dissecting or destroying the body does not help find the soul. He uses an analogy of fire in a log, which is not directly visible but can be produced through friction, to explain that the soul can be realized through specific spiritual practices.

- Weight of the Soul: He explains that weight is a property of matter (pudgala) and not applicable to the soul. The subtle karmic and heat-producing matter (tejas pudgala) associated with the soul might account for the apparent lack of weight change.

- Sealed Box Analogy: He explains that matter's nature allows for passage without necessarily creating visible holes, especially for subtle entities like the soul.

- Five Elements and Consciousness: He argues that while elements are necessary for bodily functions, they cannot account for consciousness or organized action. He uses the analogy of a gramophone or a machine that requires a conscious operator for meaningful, directed action.

- King Pradeshi's Realization: Convinced by Acharya Keshi's arguments, King Pradeshi abandons his atheistic views, accepts Jainism, and takes vows.

Chapter 2: Charvaka Matakhandan (Refutation of Charvaka Philosophy)

- Charvaka's Rejection of Soul: This chapter focuses on refuting the Charvaka (materialist) viewpoint that denies the existence of a soul.

- Charvaka's Argument: The Charvaka claims the soul is not a proven entity ("pramanasiddha") and therefore non-existent. They reject any form of proof beyond direct perception.

- Syaadvadi's Counter-Arguments:

- Scriptural Authority (Agam): The Syaadvadi argues that scriptures (Agam) are a valid form of knowledge and they consistently speak of the soul.

- Practicality of Scripture: They argue that rejecting all scriptural authority would disrupt all worldly and spiritual transactions, as knowledge often comes from trusted sources (like elders for children).

- Definition of 'Apta' (Trustworthy Person): The Syaadvadi defines an 'Apta' as someone free from attachment and aversion (ragadväsa), who has attained complete knowledge. They identify the Tirthankaras as such individuals, whose words (Agam) are therefore reliable.

- Charvaka's Doubt on 'Apta': The Charvaka questions whether such purely detached beings truly exist, claiming everyone is influenced by attachment and aversion to some degree.

- Refutation of Charvaka's Doubt: The Syaadvadi uses analogies (like refining gold) to explain that while complete detachment may not be immediately apparent, it is attainable. The degree of attachment and aversion varies, and it's possible for someone to be entirely free from them. They also point out that the Charvaka's own denial of heaven and hell is also an assertion without direct perception.

- Reasoning and Inference (Anuman): The Syaadvadi argues that even if the soul isn't directly perceived, it can be inferred. They use the example of seeing smoke and inferring fire. The invariable concomitance (vyapti) between smoke and fire allows for this inference.

- Charvaka's Rejection of Inference: The Charvaka argues that the inference is flawed because the specific cause of the smoke in the kitchen might not apply to the mountain. They claim that if something is not directly perceived, it doesn't exist.

- Syaadvadi's Defense of Inference: The Syaadvadi clarifies that inference relies on the general rule, not the specific context. The principle that smoke arises from fire is universal, and the specific context doesn't negate the general principle.

- Soul as the Inferential Subject: The Syaadvadi then applies inference to the soul: just as a tool (axe) needs an operator (man) to function, senses need a conscious agent (soul) to produce knowledge. The fact that knowledge is acquired and retained, even when senses are impaired or dead, points to an enduring soul.

- Memory and Past Experiences: The Syaadvadi argues that memory of past experiences (like taste or sight) after the senses are gone or inactive can only be explained by an underlying conscious entity (soul) that retains these experiences.

- Life Force (Prana): The Charvaka suggests that the vital force (prana) might be sufficient for consciousness. The Syaadvadi counters that prana is also a subtle form of matter and does not possess consciousness itself.

- Consciousness at Birth and Breastfeeding: The Syaadvadi uses the innate crying and feeding behavior of infants as evidence for ingrained predispositions or past-life impressions, which can only be carried by a soul.

- Jati-smaran (Recollection of Past Lives): The text mentions the phenomenon of "Jati-smaran," where individuals recall past lives, which supports the concept of a transmigration of the soul.

- Direct Perception (Pratyaksha): The Syaadvadi ultimately argues that the soul is also directly perceived, as we have an "I am" awareness separate from the body. The concept of "mine" (e.g., "this body is mine") implies a possessor distinct from the possessed.

Chapter 3: Bauddha Matakhandan (Refutation of Buddhist Philosophy)

- Buddhist View: The Buddhists believe the soul is purely consciousness ("Vijnana-svarupa") and momentary ("Kshanika").

- Syaadvadi's Counter-Arguments:

- Beyond Pure Consciousness: The Syaadvadi agrees that consciousness is a characteristic of the soul but argues that the soul is not only consciousness. There are other aspects and qualities.

- Existence of Other Substances: The Syaadvadi rejects the idea that only consciousness exists, stating that the existence of material objects (ghat, pat) is empirically evident. If everything were only consciousness, then worldly transactions would cease to function.

- Matter and Consciousness are Distinct: The Syaadvadi asserts that matter and consciousness are distinct realities.

- Illusion vs. Reality: The Buddhists argue that material objects are illusions. The Syaadvadi counters that illusions themselves are based on something real, like a mirage being an illusion of water. The existence of a real object must be acknowledged for an illusion to occur. Furthermore, if all perceived objects were illusions, then no practical actions could be performed.

- The Nature of Happiness and Strength: The Syaadvadi argues that if the soul were purely consciousness, then qualities like happiness and strength would not be distinct. However, the varying degrees of knowledge, happiness, and strength in different souls suggest they are separate qualities of the soul, not just consciousness itself.

- Suffering and Attachment: The Syaadvadi explains that suffering arises from the soul's association with karmic matter, not from its inherent nature. True happiness is the soul's natural state when free from karmic bondage.

- Momentary Existence is Flawed: The Syaadvadi refutes the Buddhist concept of momentary existence, arguing that it leads to logical inconsistencies like:

- Action without Agent: If everything is momentary, who performs an action, and who experiences its results?

- Transmigration Impossible: If a consciousness stream is momentary, how can it carry karmic impressions to the next life?

- Liberation Impossible: If everything is momentary, liberation, which implies continuity of effort and cessation of suffering, becomes impossible.

- Memory Impossible: If consciousness is momentary, how can one remember past experiences?

- Upanay of Change, Not Annihilation: The Syaadvadi clarifies that for Jainism, things undergo change (parinami) but are not annihilated. There is an element of continuity.

Chapter 4: Refutation of Vedanta, Nyaya, and Samkhya Philosophies

-

Vedanta:

- Vedantic View: The soul is one, eternal, unchanging ("Kutastha Nitya"), and the sole reality (Brahman). The world is an illusion (Maya).

- Syaadvadi's Rebuttal: The Syaadvadi argues that if the world is an illusion, it cannot produce real effects. If Maya is real, it contradicts the concept of oneness. The Syaadvadi asserts that the world and the multiplicity of souls are real.

-

Nyaya:

- Nyaya View: The soul is all-pervading, becomes inert upon liberation, and is dependent on God (Parmatma). There is one Supreme Soul and many individual souls (Jivatma). God is the creator and controller of the universe.

- Syaadvadi's Rebuttal:

- Nature of God: The Syaadvadi questions the nature of this God: if God is corporeal, not detached, cruel, dependent, and limited in knowledge, then God is not superior. If God is detached, omniscient, and kind, why create an imperfect and suffering world?

- Omnipresence of Soul: The Syaadvadi rejects the idea of the soul being all-pervading, arguing that its qualities (like knowledge) are observed within the body. They state that the soul is embodied according to the body's size.

- Liberated Soul: The Syaadvadi disagrees that liberated souls are inert or devoid of qualities. They argue that true liberation is the state of possessing infinite knowledge, bliss, and strength, free from karmic obscurations.

-

Samkhya:

- Samkhya View: The soul (Purusha) is eternal, pure consciousness, inactive ("akarta"), and devoid of qualities ("nirguna"). Prakriti (matter) is the active principle responsible for creation, bondage, and liberation. Purusha is like a blind man who sees when supported by a lame man.

- Syaadvadi's Rebuttal:

- The Doer: The Syaadvadi argues that an inactive entity cannot be the soul; consciousness must be the agent. If the soul is not the doer, then its liberation is also questionable.

- Soul is Embodied and Active: The Syaadvadi rejects the idea of the soul being all-pervading and quality-less. They maintain that the soul is embodied and possesses qualities like knowledge and strength.

- Bondage and Liberation of the Soul: The Syaadvadi asserts that bondage and liberation apply to the soul, not to an inert entity or matter.

Chapter 5: A Brief Description of the Soul According to Jain Philosophy

- Jain View of the Soul: This chapter summarizes the Jain perspective on the soul:

- Size: The soul is not inherently small or large but assumes the size of the body it inhabits.

- Multiplicity: There are innumerable souls, not a single one or a countable number. This explains the diversity of experiences and the absence of a soul-less universe.

- Karma and Soul: Souls are covered by karma, which obscures their innate qualities of knowledge, perception, conduct, and strength. This bondage is beginningless (anadi) but can be overcome.

- States of Existence: The text describes the soul's journey through various states of existence, from the most distressed (in hells and elementary bodies) to the most blissful (in heavens and as liberated souls). Humans are uniquely positioned to achieve liberation.

- Consciousness and Karma: The soul's qualities of contraction and expansion are due to karma. Liberated souls reside in Siddhashila, possessing their full essence.

- Regions of the Soul (Pradesh): The soul is described as having innumerable "regions" or "parts" (pradesh), filling the space it occupies.

- Transmigratory Nature: The soul is a "parinaami" (transforming) substance, experiencing changes in its states of happiness, suffering, knowledge, ignorance, gender, etc. This is contrary to eternalism.

- Soul Types: Souls are classified based on their propensities towards spiritual practice and liberation (e.g., Bhavya - capable of liberation, Abhavyä - incapable).

- The True Soul: The soul is defined as the doer of actions, the experiencer of their fruits, the one who transmigrates and ultimately attains liberation.

Overall Significance:

"Aatmvad" is a significant work in Jain literature for its systematic refutation of opposing philosophical views and its clear articulation of the Jain understanding of the soul. Through dialogues and logical reasoning, it aims to guide readers towards the realization of the soul's true nature and the path to liberation. The text emphasizes the importance of right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct as prescribed by Jainism.